The life and times of Dr. Alois Alzheimer — the doctor who discovered Alzheimer's disease.

Awareness campaigns, research funding drives and personal testimonies have helped make Alzheimer’s disease more widely known, and new developments occur regularly as research into the disease progresses. However, not many people are familiar with the discovery of the disease, and fewer still know about the life and work of Dr. Alois Alzheimer, the discoverer of the disease.

Who was Dr. Alois Alzheimer?

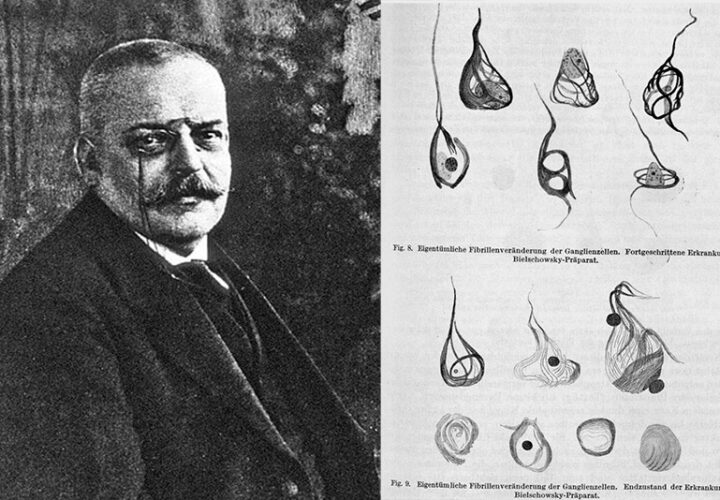

Born in 1864 in Bavaria of Southern Germany, Alzheimer did well in academics, studied medicine at multiple schools and eventually graduated with a medical degree in 1887. Dr. Alois Alzheimer then began working at a state mental asylum in Frankfurt am Main, practicing work in psychiatry and neuropathology under distinguished neurologist Franz Nissl. Alzheimer eventually assumed the role of director at the asylum. During their time together, Alzheimer and Nissl investigated the pathology of the nervous system, particularly the cerebral cortex.

Alzheimer then took up a position in 1903 as a research assistant to influential German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin at the Munich medical school. Alzheimer and Kraepelin created a new laboratory centered around brain research, and the two went on to publish several papers on diseases and conditions of the brain.

In 1906, at the 37th meeting of South-West German Psychiatrists in Tübingen, Alzheimer presented a lecture on a new disease he had seen evidence of.

The discovery of Alzheimer’s disease

In his lecture, Alzheimer described the case of Auguste Deter, a woman in her fifties with an “unusual disease of the cerebral cortex.” Alzheimer noted symptoms of memory loss, disorientation, hallucinations, and eventually her death at the age of only 55. A postmortem analysis of her brain revealed a thinner than normal cerebral cortex and neurofibrillary tangles. Alzheimer was also surprised to find the presence of “senile plaque,” which had previously only been seen in the elderly. Unfortunately, the lecture was poorly received, and Alzheimer’s research failed to gain attention.

The name “Alzheimer’s disease” itself was not coined until 1910. Kraepelin, writing a chapter on “Presenile and Senile Dementia” in the eighth edition of his Handbook of Psychiatry, included descriptions of Deter’s case, naming the disease after his colleague. By the following year, Kraepelin’s description was being used by doctors to diagnose patients with similar symptoms in the United States.

Unfortunately, Alzheimer had little time to enjoy the burgeoning interest in his research. In 1913, while traveling to Breslau, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland) to assume the role of the chair of the department of psychology at the Friedrich Wilhelm University (currently Humboldt University of Berlin), Alzheimer caught a severe cold. Complicated by endocarditis, an infection of the heart lining, Alzheimer never fully recovered, passing away in 1915 at the age of 51.

While Alzheimer is primarily remembered for his discovery of Alzheimer’s disease, he also made several scientific contributions to other neurological subjects, including alcoholic delirium, schizophrenia, brain tumors, epilepsy, Huntington’s disease and Wilson’s disease.

Alzheimer’s research today

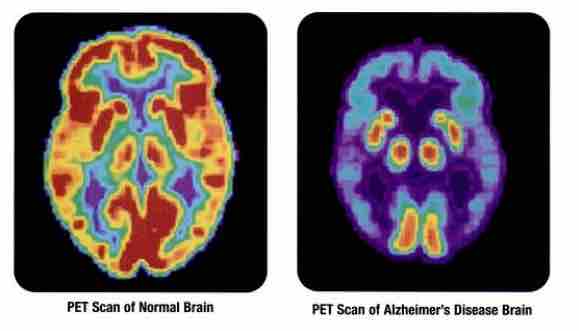

Following Alzheimer’s death, little research into the disease was conducted until the 1960s and 70s, when British psychiatrists began to investigate the importance of plaques in the brain. By 1976, neurologist Robert Katzman wrote an editorial identifying Alzheimer’s disease as the most common cause of dementia, as well as a major public health concern, reigniting interest in and awareness of the disease.

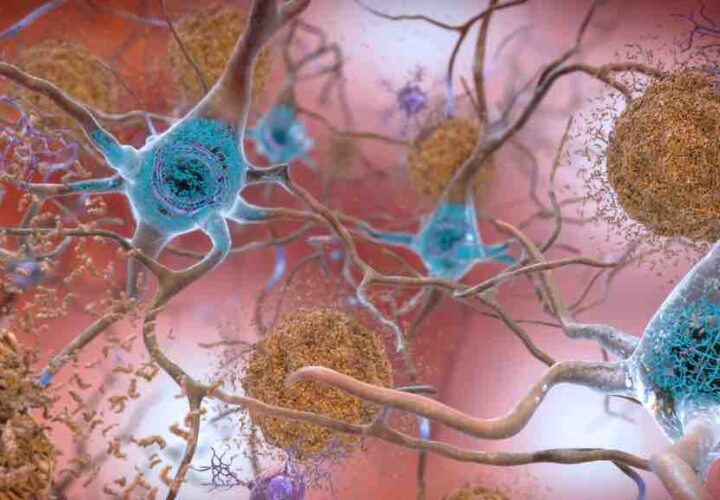

Since then, research has focused on discovering the way the disease works in the brain and how to slow or prevent its progression. Popular theories place importance on beta-amyloid and tau plaques and tangles, which Alzheimer initially compared to millet seeds.

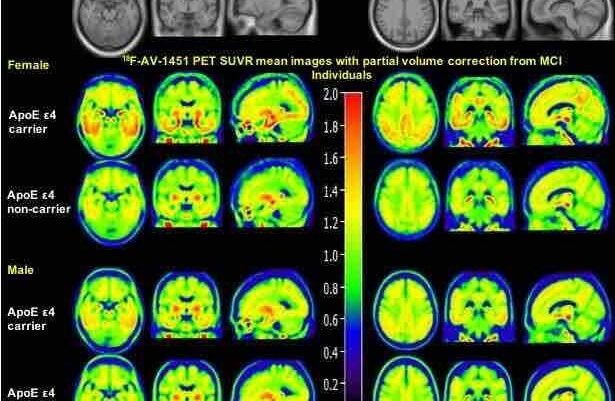

While discoverer of Alzheimer’s genes Rudholf Tanzi and other researchers believe drugs targeting beta-amyloid could stop the disease in its tracks, others have started to focus on tau tangles, as beta-amyloid drug trials continue to fail. However, Tanzi argues that trials need to focus on participants who are not yet showing symptoms of Alzheimer’s so that the drug can prevent beta-amyloid accumulation before symptoms appear.

More than a century after Alois Alzheimer’s initial discoveries, the disease named after him is now an internationally recognized and researched health concern.

From finding new genes that could have a link to Alzheimer’s or vaccines that could prevent the disease to eye tests and blood tests that could detect Alzheimer’s years before symptoms appear, researchers are continuing to study how to prevent Alzheimer’s.