For Tim Williams, a man with an extensive family history of Alzheimer’s, enrolling in a clinical trial was unknown territory worth exploring.

ApoE4, a genetic variation sometimes referred to as the “Alzheimer’s gene,” is one of the most influential genetic risk factors for developing Alzheimer’s disease. Carrying one copy of this gene raises risk a little. Carrying two copies means as much as a 60-percent increase in one’s chances of receiving an Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

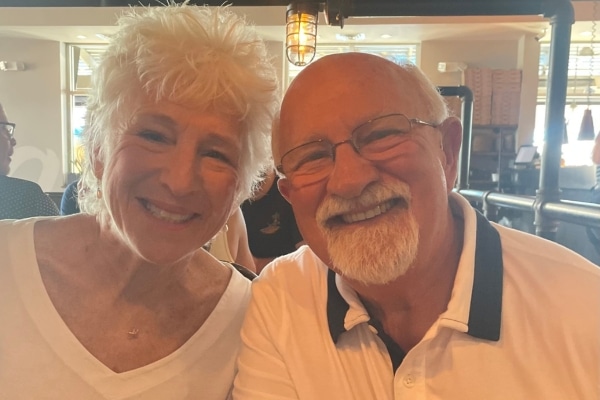

Tim Williams and his wife took the 23&Me test hoping to be armed with new knowledge of what diseases they may be genetically at risk of. A saliva sample revealed that Williams was in this high-risk group for Alzheimer’s — he is a homozygous carrier (carrying two copies) of ApoE4. Williams was not blindsided by the news, given that he has an extensive family history of Alzheimer’s. His father was diagnosed with it in 2004 and died of Alzheimer’s four years later. Williams’ sister, Beth, was diagnosed in 2019 and passed away in 2023.

Following his sister’s diagnosis, Williams founded a fundraising team called Remember the Love that participated in the Walk to End Alzheimer’s, and he began looking around at clinical trials that would give him an opportunity to get involved in research into treatments and cures. “I thought I needed to do something different and something more,” he said.

Through Trial Match, a clinical trials finder on the Alzheimer’s Association’s website, Williams found the AHEAD study and went through a several-month screening process to determine whether he was eligible to participate. One aspect of this eligibility screening process was brain imaging to look for beta-amyloid protein plaques that tend to build up in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. These hallmark plaques might be present years before symptoms appear.

“A PET scan revealed that I had either no plaque or my plaque wasn’t at a level to qualify for the AHEAD study,” he said.

But, during this screening process, the trial administrators tested Williams’ genetics again, and confirmed that, while he didn’t have the early signs of Alzheimer’s in his brain, he did indeed have two copies of ApoE4.

Williams went on to find other studies that he was eligible for, including Alzheimer’s Prevention Trial, which took place online and required memory and cognitive tests every three months.

Following another PET scan in November 2023, Williams received a call from Dr. Ian Grant, a neurologist in Chicago. Just a year after his original scan for amyloid plaques, this new scan yielded a different result: There now were beta-amyloid plaques building up in Williams’ brain.

“When he told me that I had elevated plaque in my brain, I was freaking out,” Williams recalled.

One outcome: Williams was now eligible for the AHEAD study after all. Focused on participants who are at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s later in life, AHEAD investigates possible treatment with an “anti-amyloid” drug called Leqembi, designed to slow or stop these early Alzheimer’s brain changes by clearing out the amyloid plaques.

In March of 2024, Williams re-entered the screening process for the AHEAD study through the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center in Madison, Wisconsin. The screening included blood work, memory tests, and two PET scans to look for plaque and tau tangles in the brain. He received his first infusion in August, and he commutes 85 miles each way from his home in Burlington, Wisconsin for regular infusions of the drug.

For Williams, enrolling in the study carries added risk. Homozygotes for the ApoE4 gene have significantly higher risk of brain swelling and bleeding (ARIA) during treatment for MAB drugs.

“Normally in the AHEAD study you have the MRI after the third infusion. I had one after the second one, and again after the third, because of my E4 status,” Williams said.

Williams knew he was at higher risk of side effects from the drug because of his genetic status. But it didn’t stop him from wanting to participate.

“I wasn’t nervous about it,” he said. “I prayed to God, ‘What do I do?’ I just get this feeling when God’s answering me.”

He worked with Cynthia Carlson, a nurse practitioner at ADRC, who explained the process by which the trial administrators would monitor his brain for these small bleeds, swelling, shrinkage, or other red flags of a bad reaction, and determine next steps if these effects were detected.

“She [Carlson] said that someone in our study had brain bleeds or brain swelling and then they just decided to skip the month [of infusions]. They ask that person, ‘Do you want to continue or just be done with it?’ and they [the participant] said they just want to skip the month and continue with the study.”

Williams, who is in a blind trial, doesn’t know whether he’s in the test group or the control group — whether he’s actually receiving the drug itself or a placebo. But he has experienced some side effects with his early rounds of infusions.

“During the infusion, I got crazy chills, I got a headache, I was lightheaded,” he said. “When I got home and looked at some of the side effects of lecanemab, and those are some of the side effects. The second infusion, I had the same type of things. The third one, I was lightheaded again, but I was warm, not cold.”

These effects didn’t change his mind about participating, he said. “The people at the AHEAD study in Madison are fabulous,” Williams said. “They’re all so gracious and polite and appreciative of what volunteers are doing. It’s been a wonderful experience.”

There are moments where Williams’ memory fails him, and symptoms of cognitive decline reveal themselves.

“Yesterday, when we were driving in this little town that I live in, I went from Walmart and I was going to Pick and Save and I had to think for a minute about somewhere I’ve gone hundreds of times. I had to think about, ‘How do I get into Pick and Save?’”

Still, Williams works 30 to 35 hours per week selling office furniture, and was previously an owner of an office furniture dealership for thirty years, which he sold about three years ago.

“Nothing has affected my work. Nothing has affected my day to day activities,” Williams said of his occasional forgetfulness. “I like working. It gives me something to do. I enjoy meeting people and seeing people.”

Williams is open about his status as a homozygous ApoE4 carrier and has spoken to his two adult sons about what this elevated risk means, although neither of his children are interested in undergoing genetic testing.

Williams’ wife, who also participated in 23&Me testing, is not a carrier of the E4 gene, ruling out the possibility of their sons being homozygous carriers themselves.

“My hope is, [and] my prayer is, [that] this works. What if it works and 20 years from now, I’m 87 and I don’t have Alzheimer’s?” Williams asked. “I’ve been telling my story for the last couple years and I’ve probably gotten 20 plus people involved in research because of it. It’s a wonderful thing.”

Hi, I am also on the AHEAD study but in UK. I also have had 3 siblings die with Alzheimers and wanted to help find a cure. I am now in my 2nd year on the blind study infusions. I have had no side effects and enjoy my monthly trips to London. I would encourage anyone to take part. The staff are lovely and if this helps to find a cure, why not?

Thank you for sharing your experience with us, Brenda! Clinical trials play a crucial role in advancing treatments, and it’s great to hear you’ve had a positive experience. To stay updated with the latest news on clinical trial research, feel free to sign up to our quarterly Trials Update newsletter here: https://www.beingpatient.com/bp-trials-updates/?utm_source=organic&utm_medium=social – take care.