Anxiety — which might feel like apprehension, fear, repetitive negative thinking — may be an early indicator of the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, especially when paired with mild cognitive impairment.

The idea that anxiety somehow foreshadows Alzheimer’s is not new: We have seen it in, for example, 2018 findings that increased anxiety corresponded with higher levels of beta-amyloid, the protein that forms plaques in people with Alzheimer’s disease. We also saw it earlier this year, in a 2020 study with similar findings, detecting a link between repetitive negative thinking (chronic worry) and amyloid and another key biomarkers of Alzheimer’s, tau.

Now, a new study from the Medical University of South Carolina, recently presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, demonstrates a link between anxiety and faster progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer’s.

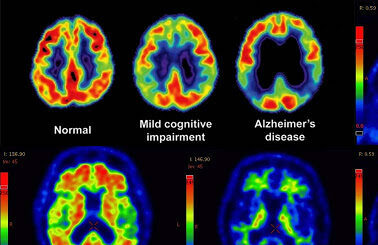

“We know that volume loss in certain areas of the brain is a factor that predicts progression to Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Maria Vittoria Spampinato, a senior author on the study and a professor of radiology at MUSC, said in a news release. “In this study, we wanted to see if anxiety had an effect on brain structure, or if the effect of anxiety was independent from brain structure in favoring the progression of disease.”

Researchers assembled a group of 339 study participants with a baseline diagnosis of MCI and an average age of 72, from the Alzheimer’s Neuroimaging Initiative 2 cohort. Of the participants, 72 were progressing to Alzheimer’s; the other 267 were considered stable. The team then conducted MRIs of participants brains, tested for for the presence of the Apoe4 allele — the most prominent Alzheimer’s genetic risk factor — and they used clinical surveys to measure participants’ anxiety.

They established the expected: that participants who had progressed to Alzheimer’s had a greater frequency of Apoe4 than those who had not progressed to the next stage of neurodegeneration, and this group also had notably lower hippocampus and entorhinal cortex brain region volume. The unexpected finding, however, was an association between anxiety and cognitive decline, independent of the neurophysical and genetic factors.

“Mild cognitive impairment patients with anxiety symptoms developed Alzheimer’s disease faster than individuals without anxiety, independently of whether they had a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease or brain volume loss,” Jenny L. Ulber, first author and medical student at MUSC, said in the news release.

This pointed to a link between symptoms of anxiety and an increased rate of progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s. The researchers speculated that such a finding could help improve screening and management of patients with early MCI — but they have yet to determine whether anxiety was a cause of the expedited progression, or a consequence of it. The study also didn’t consider gender as a factor. Future research, they noted, should do so, as Alzheimer’s is known to affect men and women differently.

It is not unlikely that at least some anxiety occurs as a consequence of mild cognitive impairment, which often precedes Alzheimer’s: MCI’s symptoms — i.e. problems with memory, language, thinking, or judgment — can certainly be a source of stress or anxiety for those experiencing them. If anxiety were, in fact, a cause rather than a consequence, however, the research team hopes it could be leveraged to provide earlier or clearer diagnoses and better treatment.

“We need to better understand the association between anxiety disorders and cognitive decline,” Spampinato said. “We don’t know yet if the anxiety is a symptom — in other words, their memory is getting worse and they become anxious — or if anxiety contributes to cognitive decline. If we were able in the future to find that anxiety is actually causing progression, then we should more aggressively screen for anxiety disorders” in older adults.

Ulber added that many hospitals already screen for depression among older adults, which is considered an Alzheimer’s risk factor and which has been found to speed up brain aging. She suggested that anxiety may be similar, and should be standardized into care for older adults.

“Middle-aged and elderly individuals with high level of anxiety may benefit from intervention,” she said, “whether it be pharmacological or cognitive behavioral therapy, with the goal of slowing cognitive decline.”