A scientist explores the biology of the blood-brain barrier — the brain's layer of protection against pathogens and toxins — and how it could help us unlock the mysteries of aging and neurodegeneration.

In the past, scientists have overlooked the vascular system’s role in aging and dementia. But increasingly, research is showing that vascular dysfunction like damage to the blood-brain barrier — various types of cells that line the brain’s blood vessels — are closely linked not only with aging but also with neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s.

Being Patient spoke with Daniela Kaufer, professor of integrative biology at the University of California Berkley, about what the blood-brain barrier is, her team’s research into its dysfunction, and what more needs to be done to better understand its role in aging and diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Being Patient: What is the blood-brain barrier?

Daniela Kaufer: It’s very rich in blood vessels and the blood vessels have cellular and molecular elements that act like a filtration system … If you get a cut in your finger or anywhere in your body, there will be a rush of immune cells to that area, but because of the blood-brain barrier, immune cells cannot cross readily into the brain tissue, for example. So [brain tissue] is protected from cells, toxins and blood molecules.

What we know is that for normal brain function, the blood-brain barrier works well and it’s a filtration system. The other thing that was known in the field for many years was the observation that [for] most neurological disorders, you will see some dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier.

[In] traumatic brain injuries, there is an actual injury to the blood-brain barrier, and we have some idea that this might actually be part of the disease development, meaning in some patients, you will see prolonged dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier. Maybe that actually causes the downstream neurological effects in those patients. We studied that. It turned out to be true, that that is indeed the case. We would open [the blood-brain barrier] locally and wait and see what happens. Over weeks and months, brain tissue will develop pathologies. We started understanding a lot of the [processes] and the steps in between. There’s a protein in the blood that actually gets access to the brain and binds [onto] the receptor and activates and there’s [inflammation] and everything that follows that.

Then we started thinking it looks very similar to something that might happen in a lot of other conditions. One of them possibly is aging and we don’t understand a lot about the natural aging of the brain. [In] the newest set of papers, we actually show that it plays a role: There is dysfunction of this barrier. We showed it in mice and in humans. [In humans], you can see that most will have an intact blood-brain barrier in their 20’s and in their 30’s. Some do not but most will. Then [in] middle age, you see [that] some people start [to have] some dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier and [at] about 70 years old, somewhere around 75 percent of the population showed some dysfunction of blood-brain barrier.

Being Patient: How do you detect blood-brain barrier damage in humans?

Daniela Kaufer: [There are] multiple ways. When we do it with patients, there’s a dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI protocol, meaning we have a contrast agent. The contrast agent is injected into the subject in IV, and if the blood-brain barrier is intact, it cannot get into the brain. If there is dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier, it will leak into the brain and you start seeing signals in the brain.

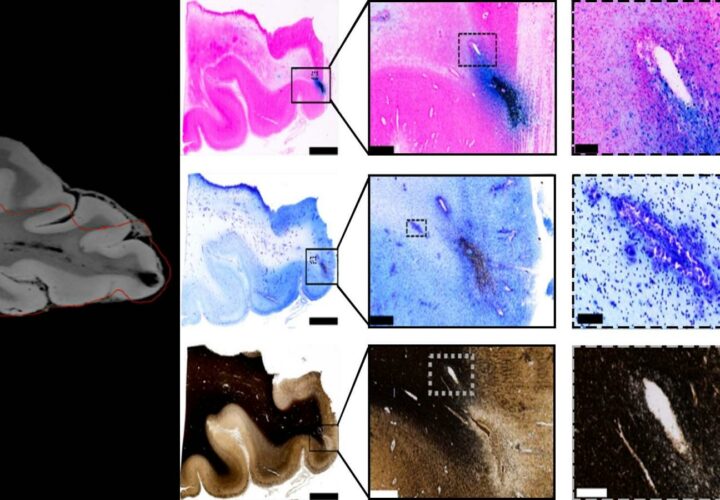

We can create maps and this is a technology that was developed by my collaborator Alon Friedman at Dalhousie University. He’s scanned at this point hundreds of patients and created an algorithm that makes a permeability map and quantifies the amount of leakage and where it is in the brain. That’s one way that we can see [blood-brain barrier dysfunction]. We could do the same MRI on our animals.

The other way is we take brain sections post-mortem, after the animal or the person is no longer alive. You can take their brain, and stain or quantify [with] other means, blood proteins in it.

Being Patient: What can cause damage in the blood-brain barrier?

Daniela Kaufer: What exactly causes this damage in the blood brain barrier? We don’t know. This is something that we’re studying now in the lab and there’s a lot of other labs that are becoming more and more interested in that. This is a neglected area of neuroscience: We know less about vascular function.

The way that we got into this field to begin with was when I was a graduate student, and Alon was a physician in the Israeli army, many years ago in the 90’s, we started with a study that looked at the effects of stress. We looked at the effect of stress and it turned out that acute traumatic stress actually causes the leakage in the blood-brain barrier as well.

But we don’t know enough yet about the mechanisms of why in some people, there’s this dysfunction [of the blood-brain barrier] and others, we see complete resilience throughout their life.

Being Patient: Are concussions associated with transient disruption of the blood-brain barrier?

Daniela Kaufer: [It] depends on who. Sometimes it’s transient. We’ve worked with football players. Some of them do not have blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Some of them have blood-brain barrier dysfunction and the next time you scan them, they’re fine. Some of them, there’s still dysfunction a year later. We don’t understand yet this dynamic effect.

It’s very clear that repeated concussions or repeated mild traumatic brain injuries are something that exacerbates [blood-brain barrier dysfunction] … When we scan [animals’] brains, we can see that there’s deterioration with each additional hit.

Being Patient: What’s the current direction of your research in the blood-brain barrier?

Daniela Kaufer: [There are] a lot of different directions. One of them is trying to [develop] a drug and we’re trying that in Alzheimer’s models as well because we know that blood-brain barrier dysfunction is actually a very early event in Alzheimer’s. We’re trying to understand the mechanism, the initial question [of] why. Why does it happen or why doesn’t it happen in some people. We’re understanding that there’s an importance to where [the dysfunction] is. You can see it in some psychiatric disorders but that’s in different brain areas. So the importance of where the dysfunction is localized [is under investigation] … We want to see the effect of your life history — stress, exercise, nutrition — all sorts of different things that can actually affect your blood-brain barrier.

Being Patient: Can you help us put into context how research into the blood-brain barrier can unlock some of the mysteries behind Alzheimer’s?

Daniela Kaufer: The key here is that it became clear to many, many different scientists that [the blood-brain barrier] plays a role in [the] mechanism of disease. It’s [not like] all we need to think about [is] how do we open it up so drugs get in? That’s where the field had been for a very long time. Now it’s clear that this is part of [the] signaling mechanism in the brain. There [are] actually pathways that are activated and there [are] many, many different layers and levels of cell activity [in the blood-brain barrier]. Once we get an understanding of that, then I think we’re going to be a lot more equipped to try to design very selective drugs and use technology for that.

One of the most important advances is gene editing. Nobel laureate Jennifer Doudna [shared a Nobel Prize for helping develop CRISPR]. If you want to do gene editing in the brain, you’re going to have to have access to brain cells, to the machinery that’s involved. I think there will be a lot more research into technologies — when I say technologies I also mean pharmacology — that let us control the cell activity of the filtration: what gets in, what gets out, the timing of that and where.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com