Two in three people have the cold sore-causing virus, herpes. While it lies dormant for most of the lifespan, scientists now think it could awaken later in life and fuel Alzheimer’s disease.

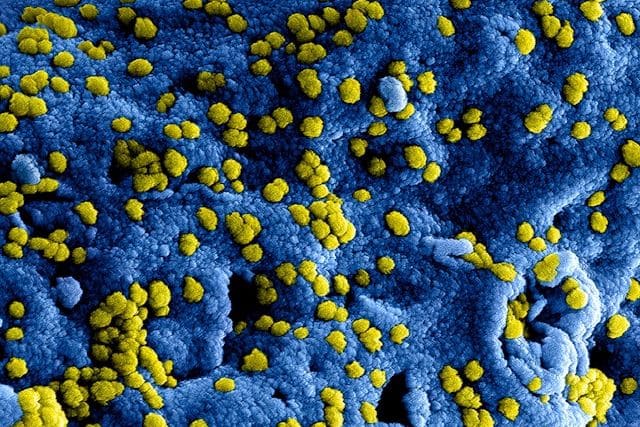

Decades ago, University of Manchester biophysicist Ruth Itzhaki made a startling discovery: Her team found the cold sore-causing virus, herpes (HSV-1) in the brains of older adults. While it’s common for the herpes virus to lie dormant inside the body’s nerves, researchers didn’t know until this discovery that it could reach the brain.

That left them asking bigger questions about the virus’s long-term impacts: Could the virus come out of its dormant state and disrupt the brain’s immune system, too? If so, could it contribute to Alzheimer’s disease? And last but far from least: If the cold sore virus making its way into the brain ultimately proves to be a driver of Alzheimer’s, could antivirals that are already approved to treat herpes infection be the answer?

So far, they’ve found some strong evidence: Observational studies to date have shown that people with the Alzheimer’s risk gene ApoE4 are more likely to have an HSV-1 infection, and several observational studies—including one published in 2025—found that infection raised the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease up to 13 percent.

Other such studies found that people who took antiviral drugs to treat the herpes infection ultimately had a lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s than people who let a herpes infection go untreated.

While these observational studies provide plenty of clues, they leave some very important questions unanswered: Research to date hasn’t been able to reveal any potential mechanism for how exactly the virus gets into the brain. And, importantly, observational studies can’t prove causation — they’ve stopped at shedding light on a strong, and intriguing, link.

But good news: Now, a trio of new studies into herpes and brain health brings new data explaining how the virus might spark Alzheimer’s and whether antivirals could protect the brain.

Does herpes explain why TBI increases Alzheimer’s risk?

According to the World Health Organization, almost two in three people under 50 have already caught the cold sore-causing virus, herpes. While the virus might occasionally reactivate during stressful situations, for the most part, it lays dormant and doesn’t cause symptoms.

So, if so many people have been exposed to this infection in their lifetimes, and the link between Alzheimer’s and herpes is so strong, why don’t far more people go on to develop Alzheimer’s?

The first of three 2025 studies, published in Cell Signaling, provides proof that the virus awakens after traumatic brain injuries — and this might explain why repeated concussions increase the risk of Alzheimer’s and other dementias.

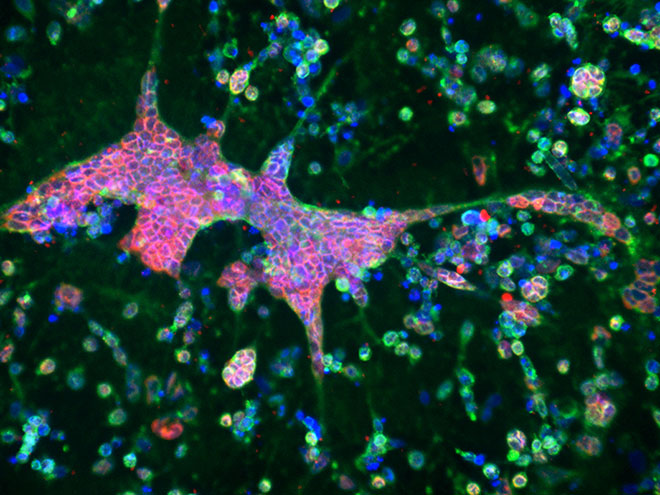

In the study, researchers infected lab-grown mini-brains with the herpes virus. The virus only became active after researchers simulated a brain injury, shaking and damaging the mini-brains. As the HSV-1 reactivated, it caused inflammation and the production of beta-amyloid, hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.

A genetic helper behind the scenes

Published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia, the second 2025 study provided more evidence that the herpes virus affects the brain’s immune system.

Scientists looked at the post-mortem brains from 393 people who died of Alzheimer’s and 199 cognitively healthy controls to look at the impact of a herpes infection. Researchers took samples of patients’ brains shortly after their deaths to analyze which genes brain cells had activated. Looking at active genes provides clues into what was going on in the brain while the individual was alive.

People who died of Alzheimer’s were more likely to have the herpes virus in their brains. The viral infection led to the dysregulation of a gene involved in the brain’s immune system called NEAT1. The researchers confirmed this finding in a lab-grown mini-brain.

Could antiviral drugs protect the minibrains from HSV-1? Researchers then treated the mini-brains with a common herpes treatment, valacyclovir, and found it mitigated the inflammatory effects of the virus. This finding suggests a possible mechanism by which these drugs could reduce Alzheimer’s risk: by tidying up the dysregulation of NEAT1.

Hit and Run: How Viruses Could Spur Alzheimer’s—and How Vaccines Can Help

What happens in vagus doesn’t always stay in vagus

A third study looked at a virus called cytomegalovirus (HCMV), which belongs to the same family as the cold sore herpes viruses. While HCMV is known for infecting the gut and lying dormant, researchers discovered it may travel from the gut to the brain, hitching a ride on the vagus nerve that connects them both. Once there, it may spark inflammation that could contribute to Alzheimer’s disease.

“I think it’s possible that this particular virus in a subset of people kind of tips them into a disease state,” associate research professor at Arizona State University Ben Readhead, who co-led the study, told Being Patient. However, he cautioned that more research is needed.

Trials studying the herpes-Alzheimer’s link

Taken together, these three new studies paint a compelling case that the cold sore virus, once thought of as relatively harmless, may be an important factor in Alzheimer’s disease.

“It also opens the door to possible new ways of preventing the disease, such as vaccines or antiviral treatments that stop the virus from waking up and harming the brain,” Itzhaki wrote.

The final test to definitively prove that the herpes virus is a major causal or contributing factor for Alzheimer’s disease would be a gold-standard clinical trial that could show without a doubt that treating the infection slows or prevents the disease. If antivirals treat cognitive symptoms or prevent the disease altogether, it could provide another option for a subset of patients where HSV-1 might be driving the disease.

Dr. Davangere Devanand, a Columbia University neurologist, recently wrapped up a Phase 2 trial testing an antiviral drug that treats herpes to see if it could slow down Alzheimer’s disease. The results haven’t been published or presented yet.