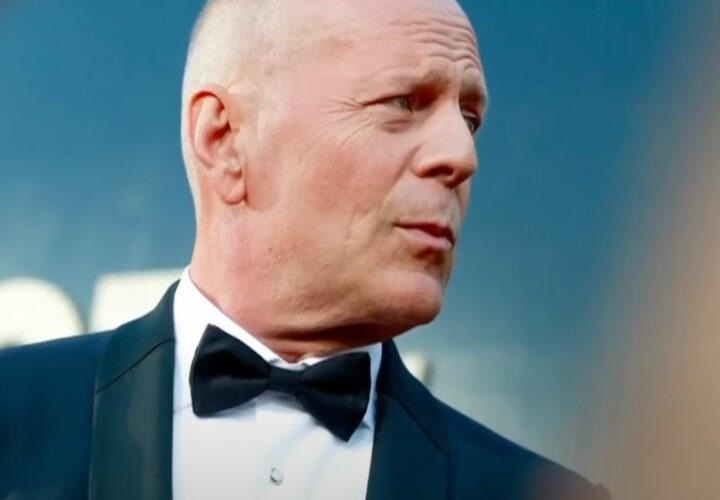

Following the announcement of Bruce Willis's dementia diagnosis, Massachusetts General Hospital’s Dr. Brad Dickerson and Katie Brandt dig into frontotemporal dementia (FTD) from a caregiver and medical perspective.

With the news of Bruce Willis’s diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia, many have questions about the diagnosis and what to expect. Katie Brandt and Dr. Brad Dickerson joined Being Patient Live Talks to help answer our community’s deepest questions about caregiving and the diagnosis of FTD.

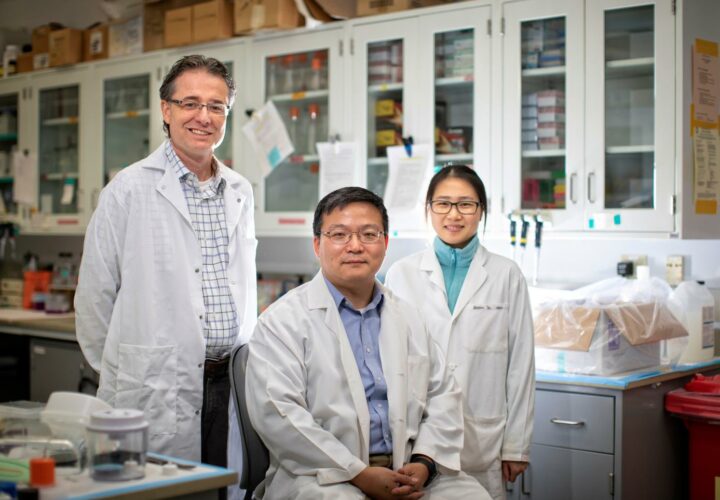

Brandt, who has spoken with Being Patient previously on the impact of her late husband’s frontotemporal dementia diagnosis, advocates for awareness from the caregiver’s perspective. She’s also the director of caregiver support services and public relations for Massachusetts General Hospital’s Frontotemporal Disorders Unit, a lead volunteer with the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration (AFTD), and a co-facilitator of the Boston area FTD Support Group.

Dickerson, an advisor for Being Patient, is the Director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Frontotemporal Disorders Unit and Neuroimaging Lab in Boston. He is also a staff behavioral neurologist in the MGH Memory Disorders Unit and co-investigator on the Neuroimaging Core of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. Both will share their insights and answer reader questions about frontotemporal dementia.

In this conversation, Brandt and Dickerson provide insights from their work as educators and advocates for FTD in Boston and around the country. Watch the full conversation, or read a transcript from the conversation below.

Being Patient: At what stage does one have to be in to get an accurate diagnosis of FTD?

Dr. Brad Dickerson: FTD is much less common than Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s in the same family of conditions that develop in the brain as a neurodegenerative disease that gradually begins to cause symptoms in a person probably some number of years after the disease begins in the brain. Depending on exactly what type of disease it is and where it is in the brain, it can produce a variety of different symptoms.

So, with FTD, it tends to be a younger age of onset for reasons we really don’t understand than Alzheimer’s disease. It tends to strike the front parts of the brain rather than the back parts of the brain, which in general, is what Alzheimer’s does. And when people, for whatever reason, develop their illness, their disease is in the brain.

Most people on the left side, if they’re a right-hander, may start out by having language symptoms. And so, their initial symptoms may best be best described as aphasia, which gradually progresses over time other patients develop changes in personality and behavior that often are very distinct from those of patients with progressive aphasia, and those are because the disease starts in a different part of the brain.

Being Patient: What is aphasia exactly? We heard initially that Bruce Willis had a type of aphasia, and we know that types of aphasia can develop into FTD. So, what is the link, and why does it develop?

Dickerson: As Katie and I have discussed extensively, it’s so important for the community of people living with this rare disease for someone like Bruce Willis and his family to disclose this diagnosis. So, it really matters to many people out there, which I know Katie will get into in more detail. But, aphasia is a problem with communication.

It can be a problem with expressing yourself linguistically in language, a problem with understanding what other people say to you, or a mix of both. And so, when a neurologist typically thinks about a patient with aphasia, they think the patient might have had a stroke, or they might have had a brain injury. But those are usually pretty sudden, what we know is that a lot of people may develop a gradually progressive difficulty expressing themselves in words, and this isn’t just coming up with someone’s name.

Many of us have that, and we don’t have aphasia. It’s more than that, and it affects communication in a greater way. So, for some number of years, it may be completely isolated and may be gradually progressive aphasia, which is often referred to as primary progressive aphasia because the main problem is language. Sooner or later, and in almost everyone with that condition, other cognitive or behavioral symptoms will develop, turning into a more general type of dementia. Sometimes it’s caused by FTD, and sometimes it’s caused by Alzheimer’s disease, and sometimes it’s one of the related diseases.

Being Patient: Katie, your husband, was diagnosed with FTD very young, at the age of 29. What were some of his first symptoms like?

Katie Brandt: Well, my husband was a little bit different than what we suspect Bruce Willis is living with, right? We’ve heard of those early symptoms of aphasia. As Dr. Dickerson just mentioned, when it happens in another part of the brain, you can see early personality changes, and that’s what I saw. So my sweet husband, who was very outgoing, became very withdrawn.

He was making a lot of impulsive decisions and just generally seemed like a different person. One thing that really struck me when I heard about the, you know, Bruce Willis’s announcement was that they had a difficult journey themselves with diagnosis and how I brought my husband to eight different medical professionals.

It wasn’t until we were with the chief of Neurology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston that we received an accurate diagnosis with Dr. Albert Galaburda. He said to me, you really need to be with Brad Dickerson’s group because they’re experts in FTD.

I think that whether we’re talking about the medical support that you get, the community support, or the care support, understanding your loved one’s specific diagnosis is important so that you can get expert care. That specific information can really just make the journey so much easier to navigate for everyone.

Being Patient: So that actually exemplifies that you had access to good medical care, as presumably, the Willis family does. So, let’s go through the playbook. Dr. Dickerson, what do you ask patients to determine if it’s FTD or not? Can a simple MRI or CAT scan give us any indication as to whether or not it’s FTD?

Dickerson: Like anything in medicine, the symptoms and signs that a person is experiencing of their illness are best recognized by someone that’s very experienced in dealing with that illness as a medical professional. So much of what’s involved is the experience of the practitioner.

Many neurologists might have seen one or maybe two patients with FTD or progressive aphasia in their entire careers. It’s a rare disease. So when you are not gaining access to someone that’s a specialist, it can be difficult to figure out if that’s the right diagnosis or not. Many patients and families will advocate for themselves to try to gain access to a specialist. But as we know, there aren’t enough of us.

“It’s so important for the community of

people living with this rare disease

for someone like Bruce Willis and

his family to disclose this diagnosis.

It really matters to many people out there.”

I think that typically a good history, finding out what’s going on with the patient’s symptoms in their daily life, and a good assessment in the office with testing and examination. And usually, a brain MRI scan might be plenty to make a diagnosis confidently of FTD early in the course of the illness, or you might need more specialized testing, like a PET scan, in order to figure it out. A lot of those things are, you know, best recognized by an experienced specialist that knows what FTD looks like.

Being Patient: Katie, in your experience, what do you recommend patients should be asking to help aid a more accurate diagnosis?

Brandt: I like something that Dr. Dickerson has said in the past, which is that, especially with the very young, you know, people that have early behavioral and personality symptoms, it can look like a psychiatric condition, but then it keeps getting worse over time. I think that’s when you want to go back to your medical provider. One thing I could say is I brought my husband to eight different medical professionals. He spent a week in a secure psychiatric unit, and so many people told me he had depression or severe depression, and it just didn’t feel right.

I just want to say to every family member out there if it doesn’t feel right, I want to empower you to keep going. You know, really ask to join that medical appointment with your loved one. If you can’t join the medical appointment, you can communicate with your loved ones’ medical provider.

HIPAA prevents healthcare professionals from sharing information, it does not prevent them from receiving information. So really everyone should hear that, like think about it. You know, Dr. Dickerson can receive an email or a note from a concerned family member that he can read and think about, is this relevant during my evaluation? That’s not, you know, breaking any confidentiality.

“If it doesn’t feel right, I want to

empower you to keep going.”

Being Patient: What types of symptoms, in terms of behavior, manifest in FTD?

Dickerson: Major depressive disorder is a disorder of the frontal systems, as well as other systems of the brain. So, it’s not surprising that some of the symptoms might look in some ways similar. With FTD, I think of three main types, and there’s a lot more nuance to this. But there’s the nonfluent type of progressive aphasia, and that’s where people have trouble getting words out in grammatically correct sentences.

It’s always important to get someone else’s perspective on this because many patients may have complete insight into their symptoms, and others may only have partial awareness of what’s going on. But the patients with the nonfluent type of progressive aphasia will often say, “I can’t get the words out in a normal way,” and that flow is like a sentence. You can usually hear a problem in the way they’re speaking, which is often more monotone or more choppy, and fragments of sentences, and that’s typically an expressive aphasia.

Patients with the semantic variant of progressive aphasia don’t understand what less common words mean and often have a lot of trouble figuring out how they can get the word out that they really want to get out. That’s a lot different than just most of us having, taking longer to come up with the word that we specifically want to use. It’s more of a situation where someone might say, “does a cork float in water?” And the patient might say, “what’s a cork? I don’t even really know what that is.” It’s really quite striking when you see it, but at the beginning, it can be subtle.

Then the third type, which probably is the most common, is the behavioral variant. That’s really what you were just asking about, which is where people often do things that may not be appropriate to the situation they’re in. We call that disinhibition. Loss of filter is what a lot of family members will refer to it as they may become what looks like obsessive-compulsive.

Even when you ask them, “why are you doing those things,” they’ll often not even realize that they’re collecting, organizing, or hoarding things in a way that their family member reports on. For other people, it may look like they have substance abuse or an eating disorder type problem because they have a very specific fixation on certain kinds of foods or on drinking drinks, including alcohol, but sometimes including other kinds of drinks. So as you can imagine, it’s much more common for people to have psychiatric illnesses that present these types of symptoms.

So, it’s reasonable that many professionals think of that first. Because it’s a lot more common, even though when you’re trained and experienced in this area, you recognize that the nature of the symptoms the person is experiencing, and often their inability to really talk to you about them, differentiates a person with FTD from a person with a primary psychiatric disorder.

Being Patient: When people come to your office for an FTD diagnosis, what type of scan do they get?

Dickerson: We think that it’s important if we’re concerned about an organ in the body, like the brain, to get a look at it. So, it’s unfortunately surprising that people don’t always think that way as medical professionals. But if we think that the person might have a brain disease that is causing their symptoms, we get a brain MRI very routinely, no problem insurance pays for it, it’s completely reasonable. And if they have FTD, Alzheimer’s disease, or another neurodegenerative disease, you may be able to see shrinkage of certain parts of the brain that a neurologist would typically expect to be abnormal in a person with the particular kind of symptoms they have.

Many times early in the illness, the MRI may not show very much. In that case, we may need to go to what’s called an FDG PET scan to get a measure of the functioning of the brain. That’s generally a more sensitive test, but it’s less readily accessible for people even though it’s paid for by Medicare routinely in an evaluation for a patient suspected of having one of these diseases.

Being Patient: What are the hallmarks that you’re looking for in those scans? Is it just shrinkage or atrophy?

Dickerson: The disease in the brain is different from Alzheimer’s, even though one of the proteins is the same protein that’s affected. So, these are all normal proteins in the brain that have important regular functions, and something goes awry with them.

They start to basically rust and twist and tangle and aggregate within the cells with FTD. One major type is called the FTD tau, and that’s the same tau protein that you’ve talked about what’s involved in Alzheimer’s. Along with the amyloid plaques, there are tapped tau tangles in Alzheimer’s. But, what exactly goes wrong with the tau in the brains of people with FTD is different than in Alzheimer’s with the tau, but there’s no amyloid.

The other type of FTD is called TDP 43. So, FTD TDP 43 was only discovered in 2006, and it also is the same protein that builds up in the brains of people with ALS. So, FTD is one of these examples of a neurodegenerative disease like some others, where there are clear linkages or relationships to some of the other diseases that may be thought of as completely distinct but probably, at a biological level, have important overlaps.

Being Patient: Katie, how did the progression of symptoms happen with your husband? Did it change rapidly?

Brandt: Initial symptoms got worse, but I think that what is so difficult about FTD is that it strikes people at the prime of life. So, if you think of Mike and me, just like many other families with FTD, we had a mortgage to pay, and we had student loans. He had a small business that he was running, he was a teacher, I had a full-time job, and we had a new baby. So, when you build your life, expecting that you’re in a partnership, you have two incomes, and then all of a sudden, one person in the partnership doesn’t seem the same. Like Mike became kind of apathetic about work.

His work product was not of the high quality that his customers were used to. He wasn’t able to do all the tasks, I suddenly didn’t feel comfortable leaving him alone with our son. So, I didn’t have a co-parent, and I didn’t have a co-income earner. So what happens is in the early stage, all the scaffolding of your life falls apart, and I think later, you build new scaffolding, right?

For medical care and home care, maybe you connect with a community-based Memory program, but it’s in those early days when so many things are unknown. And there are resources, right? If you get a diagnosis, you can get Social Security Disability, very likely. Maybe your loved one has a disability policy at work, and it matters if they just quit their job because they’re no longer interested. Or if you have that medical evaluation that says no, this person needs to leave work because of a medical condition. So early on, an accurate diagnosis can affect the day-to-day lives of families, and it definitely did that for us.

Being Patient: One of our viewers had questions about the motor types of FTD, particularly CBS, and PSP. Could you tell us more about that?

Dickerson: FTD, unlike many of these other related diseases, sometimes affects people’s cognition. Language is a major cognitive skill, sometimes affecting people’s socio-affective function or behavior, that’s the behavioral variant, and sometimes affecting their motor function. So corticobasal degeneration (CBS) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) are two conditions that are part of the FTD spectrum in terms of the diseases that fall under this umbrella of diseases.

They used to be thought of as related to Parkinson’s because they cause some of the kinds of motor symptoms that are at least reminiscent of Parkinson’s, but it’s the same protein in the brain as what’s going on in FTD tauopathies. So, we now classify them that way. Many patients with those conditions also have cognitive changes, like language or other functions, or mood and behavior changes, like behavioral variant FTD. So those two conditions can really be a spectrum as well. A couple of celebrities that have been affected by PSP are Linda Ronstadt, who just came out about that not too long ago, and Sir Dudley Moore, who played Arthur back in the day in the movie.

Being Patient: How do caregivers and families advocate for their loved ones? Do you have any top recommendations?

There are probably so many things that I have learned from the journey. The biggest is that you’re not alone. I think that when I received the diagnosis from my husband, I had actually never heard the term frontotemporal dementia or frontotemporal degeneration before. I felt so alone like we were the only people in the world going through this rare condition, and that’s just not true.

We don’t have a cure today for these conditions, but we do have a cure for the isolation and loneliness that may come along with a diagnosis. So right away, I tell people you need to speak with an elder law attorney. And then the second is to get connected with your disease community. So, if you have Alzheimer’s disease, go to the Alzheimer’s Association. If you have FTD, connect with the Association for frontotemporal degeneration, and find a support group.

It’s okay to shop around. So, if you go to one support group and you say, “I didn’t like that. That wasn’t for me,” go to a different one. Maybe we’ve had people that have come to one support group, and then they don’t come back for a year. Just know that this is a community that is very welcoming and supportive. And if I could say one thing to myself from a decade ago, I would say to ask for help earlier because it’s just so unrealistic that you could provide all this care and support by yourself.

“We don’t have a cure today for these conditions, but we do have a cure for the isolation and loneliness that may come along with a diagnosis.”

Being Patient: What are FTD patients, if anything, prescribed to manage symptoms? In addition, what’s going on in research?

Dickerson: There’s been a ton of progress made, but the meaningful treatments are still a ways off, unfortunately. So, the treatment for patients with FTD is broad-based, but it’s primarily supportive if a person has progressive aphasia. Speech-language pathology therapy is very important. Speech therapy can really make a difference in people’s ability to try to compensate for the problems they’re having.

It doesn’t help them recover as it does in patients with stroke-related aphasia, but it can help them and their communication partners communicate more efficiently with each other. So, medications may play a role, but for the most part, they’re treating symptoms, and it’s all off-label. None of them are approved specifically for FTD. We’re using medications that are typically approved for other types of conditions to treat symptoms that can sometimes really make a difference in people’s quality of life.

In terms of the research, working toward more impactful treatments, there’s a global effort. There’s something called the Global FTD Prevention Initiative, and that’s an effort across multiple countries to work with our industry partners and our academic colleagues to try to really develop the treatments of the future. There are clinical trials going on right now.

We’re just a ways behind Alzheimer’s disease in terms of the number of trials that are going on, but look for that to change before too long because I feel like there’s a real acceleration of our understanding of the underlying biology of FTD and some improvements in biomarkers. That’s another place where we need to really make some good progress because a lot of what helped the Alzheimer’s community is biomarkers for things like the amyloid plaques, and we don’t have those yet for FTD.

Being Patient: What does the end stage of FTD look like? Like, is it similar to other dementias, or does it converge in the end?

Dickerson: I was pausing because Katie, you’ve worked with so many people to help guide them toward brain donation. And it’s such an important process that you go through. So, we’ve followed many people to that end-stage and to the precious, unique resource of brain donation for advancing science and gaining closure on the disease.

I think, in many ways, the loss of functioning in people is pretty similar by the time they get to the advanced stage of FTD as it is in people with Alzheimer’s, but there are some differences. There’s often a more focal degeneration in the front part of the brain and FTD, even toward the end, with remarkable sparing at the back of the brain. Some of the things the back of the brain does is help you recognize family members. So, you know, there may be a little bit of a difference in that in people with FTD. But in general, the loss of function is such that people are typically unfortunately not able to do anything for themselves and not really able to interact much with loved ones.

Brandt: I think when we think about care at the end here, I just want to put a plug-in for palliative care and hospice services. If your loved one is living with moderate to severe stage dementia of any kind, reach out to your local palliative and hospice care agencies and ask for an evaluation.

Find out what you’re eligible for to help you protect personhood and dignity, your goals of care at every stage. For me, that was incredibly supportive. I felt like it was a gift to our family in the end. And then, when I made the choice to donate my husband’s brain, it finally felt like my first power play against the disease that was trying to run everything about our family’s lives.

“When I made the choice to donate

my husband’s brain, it finally felt like

my first power play against the disease.”

Being Patient: Did you get a report about the autopsy on his brain? What did you learn?

Brandt: I did, and I remember sitting in my living room, and Dr. Dickerson and I were talking on the phone so that he could explain the autopsy report for me. The biggest thing he gave me was the gift of being sure that Mike was living with FTD, and that is what he had. I didn’t leave any stone unturned. I brought him to the best place. I did what I could. The mystery was uncovered through that gift. If you’re interested in brain donation for your loved one, the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration is hosting a webinar next week about brain donation, so you can go to learn more about it.

Being Patient: Is FTD genetic? Do people need to be concerned about passing along this gene?

Brandt: As I said, when Mike was diagnosed, that was the first time I had ever heard of FTD. So, no one in his family had it. You know, of course, every family, when their loved one is diagnosed with anything, right, whether it’s colon cancer or Alzheimer’s disease, they worry, “Oh, my goodness, what is the reality for me?”

I cannot say this enough. Don’t listen to your neighbor or your Aunt Mary, who’s saying things that could be upsetting; speak with an expert and learn the facts. That can help you make plans for your own healthcare decisions and your loved ones.

Dickerson: FTD can run in families. Most of the time, it’s what we call sporadic, which means it affects the person that comes down with it, and there’s no history of anyone else in the family that’s had similar symptoms. It’s important also to recognize that sometimes other people in the same family may have had related conditions that might have been diagnosed as Parkinson’s or might have actually been ALS. I mean, these conditions run in families in ways that are not stereotyped.

It’s not necessarily true that the person that might have the same disease in the family had exactly the same symptoms. I like to talk to people saying, “tell me about your dad? what happened to him as he entered the later stages of his life?” “Tell me about your mom.”

I really like to go through family history and details like that. It turns out that probably somewhere around 15 to 20 percent of people with FTD have a family history of something that might be similar. Right now, about 10 to 15 percent of people have a pretty clear family history from generation to generation of the same type of thing. We can explain many of those cases with one of three major genetic mutations that have been identified over the years that are now being taken advantage of in ways that hopefully will lead to a better biological understanding of the disease and, ultimately, opportunities to try to treat it and maybe even give people treatments before they develop symptoms.

Being Patient: What genes are associated with FTD?

Dickerson: There’s one called MAPT, and it’s the gene that makes the tau protein. So, if you get mutations in the gene that makes the tau protein, you get FTD, but you don’t get Alzheimer’s disease. Even though interestingly, there have been a lot of animal models in the laboratory that have been developed using mice with the map T mutation to study tauopathy to try to develop treatments for Alzheimer’s, that’s really an FTD mutation.

Then there’s progranulin, which is on the same gene as MAPT, and they’re both on chromosome 17. That leads to the TDP 43 type of FTD, and then there’s C9 or F72, which is just letters and numbers, but that was discovered in 2011 and is the thing that links families where some members have FTD, and some members have ALS. So, that’s one of the major genetic causes of FTD, or ALS or combinations of the two.

Being Patient: In terms of FTD, how do you know what stage you’re at? How can you track where you are and how you’re doing?

Dickerson: The key is the loss of independent functioning. So, the way I like to think about it is, if you can’t work anymore because of your mild cognitive symptoms that are making it hard for you to be able to get your job done, and you have to take a medical disability, you are probably at the very mild stage.

If you have a little bit more trouble, and maybe you really are getting lost, and it turns out that you can’t drive independently any longer in a safe way, that’s probably at the mild stage, but you may still be able to sit and have a pretty reasonable conversation with people about complex topics. At the moderate stage, people are starting to really have difficulty with what we call instrumental activities of daily living, like using devices in the kitchen or around the house or dealing with things outside the house independently.

Once you start to have trouble in general, and this isn’t true for exactly everybody, but in general, with basic activities of daily living, like getting dressed and taking care of your bathroom routine, and making sure that you eat— that’s usually the severe stage.

That stage for some people, especially younger people, can last for years. It can last for a lot longer than you would expect, which is why it can be tough for families to try to figure it out. You know, how much longer does this person likely have to live because they seem so impaired relative to their previous status? We just don’t know what the indicators are. So that’s where I think, you know like Katie was saying, getting a palliative care consultation can be invaluable in trying to plan ahead and trying to predict what’s the likely lifespan that this person may have left. And it’s always a range. We never know for sure, but it’s a long journey, even at the end stage, for many people.

Being Patient: What’s the biggest thing people should know ahead of time about FTD?

Brandt: I would just plant the seed that, you know, your loved one was living a rich, full life before this diagnosis. Where they went out in the world, worked, and had friends outside of you, their primary caregiver.

“It’s a long journey, even at

the end stage, for many people.”

So, helping them to maintain that, whether it’s through participation in an adult day health program, a connection with a companion, or a caregiver that understands their condition and can bring them out to engage in activities that are meaningful to them and with purpose. I think that nobody wants to be bored. Everyone wants to feel that their life has purpose and meaning, including people living with a diagnosis of FTD.

Being Patient: Katie, we have a question for you from the audience. How did you explain your husband’s condition to your children? What would you recommend?

Brandt: There’s a lovely book called Ellie’s Butterflies that’s written about a little girl who has a grandfather with FTD. But, you know, one of the things that I really noticed talking with my son is when he was very young; actually, he didn’t have a lot of questions.

He just accepted that his dad and his grandfather were as they were and that they weren’t good at remembering things. In fact, his dad didn’t talk for most of his life. But he remembered his dad laughing a lot, and he just accepted him that way. I often think it’s children who are elementary age and above that need more explanation about, you know, something is going on in dad or grandpa’s brain, and they need extra support. These are the ways that we can help them because I think kids want to feel like they know they can be helpful, too.

Being Patient: Dr. Dickerson, what are some of the questions that you’re being asked over and over again about FTD? What are some of the patterns of things that come up all the time?

Dickerson: Well, I think at the end of the day, One of the things that are most upsetting to most people living with these conditions is the disruption of their relationships with their loved ones. I think that there are a growing number of efforts, not just pharmaceutical treatments and the development of new medications, but a huge number of ideas that are being developed and worked on for behavioral intervention strategies and other ways to try to promote a better quality of life for a longer period of time, even if the disease is continuing to progress.

We’re seeing a lot more funding from the National Institutes of Health focused on not just Alzheimer’s disease but related disorders, and FTD is one of the big related disorders. So that’s targeting not just the understanding of the science of FTD but also better evidence-supported ways to live with FTD within families and within communities. I think that every year, we see the funding go up.

That brings more people with creative ideas into the field, and I think we’re gonna see more efforts to really impact people’s daily lives, even while we’re working on trying to develop better treatments for the future.