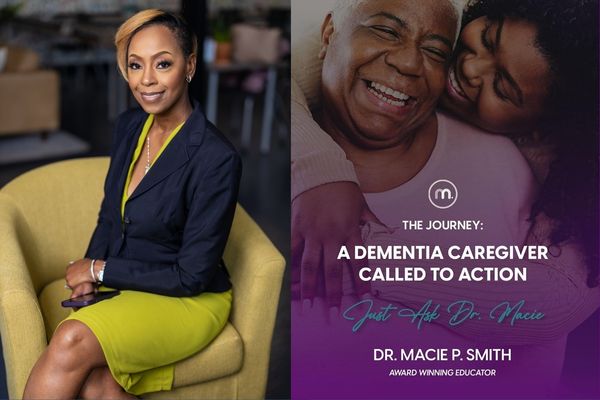

Award-winning dementia educator and best-selling author Macie P. Smith, PhD has coordinated care for aging and vulnerable populations for decades. Here's how she says we can better support caregivers in the Black community.

This article is part of the Diversity & Dementia series, produced by Being Patient with support provided by Eisai.

Black Americans have nearly double the risk of getting Alzheimer’s compared to their white counterparts, yet they’re underrepresented in drug trials and often have barriers to accessing care. For caregivers in the Black community, it also can be difficult to get the support and information they need.

That’s why educators and social workers like Macie P. Smith, PhD are trying to ensure caregivers can get the resources they need. Smith is an award-winning Alzheimer’s and dementia educator and best-selling author who has coordinated care for aging and vulnerable populations for decades. For her, best supporting caregivers in Black communities — as they confront these challenges of higher health risk, more limited resources, and less accessible care —is all about sharing resources and information where the people who need it can find it.

“I just refuse [to stand by and let] someone to actually remain in a state of crisis when they don’t have to,” Smith explained. “I feel like my job, role, and passion point really is to break down those complex ideas into basic, tangible, relatable items of interest.”

Smith breaks down dementia caregiving in her latest book, A Dementia Caregiver Called to Action: The Journey. She joined Being Patient reporter Mark Niu in a conversation about her newest book and her insights on dementia caregiving in Black communities.

Smith has over 22 years of experience coordinating care for aging and vulnerable populations. She also wrote the best-selling book A Dementia Caregiver’s Guide to Care: Just Ask Dr. Macie, and she’s also an advisory board member with Leeza’s Care Connection. Read or watch the conversation below.

Being Patient: Where did your journey into dementia care begin?

Dr. Macie P. Smith: Well, I’ll tell you. My [undergraduate] degree is in social work, and my master’s is in rehabilitation counseling. I thought I would be working solely [with] individuals with intellectual and physical disabilities for a short span of time. Then I would move on to this “glamorous” career as a licensed social worker, owning my independent practice. Well, it didn’t quite go that way.

We took a lot of detours. The first job I had in my field was with the state agency on disabilities and aging, and no matter how much I tried to leave that industry and get another job, nobody would even call me for an interview. I knew my bills had to be paid, so I said, “I might as well just stay here. Rock it out. Do what I know to do best.” That’s what I did because nobody else would hire me.

Then, my grandma developed dementia. We didn’t know what type of dementia she had, but I was well positioned by that time to provide support and care for my family, which was my dad, who was her primary caregiver, and my sister, who lived closer to her.

It was just so divine how it happened because I was sitting at my desk at the agency managing the care of over 100 individuals who were aging [and] disabled. Several of them were diagnosed or misdiagnosed with dementia. I started my training in dementia-competent practices and started doing more research.

When my grandma developed it, it still looked a little different. I still was dumbfounded. I still didn’t know exactly what to do. I thought until I had to compartmentalize my roles, and I had to take on the role as the licensed social worker, later gerontologist, to be able to help my family navigate the long term care system, which is confusing for no reason at all, but then also to provide that level of compassion and empathetic support to my family, but most importantly to my grandma, as she journeyed through the disease process.

“I had to take on the role as the licensed

social worker, later gerontologist, to be

able to help my family navigate the

long term care system… but most importantly to

my grandma, as she journeyed

through the disease process.”

It just snowballed from there because I felt that I was good at it because of the reports I’ve been getting and the stories of how caregivers talked about how the basic information changed how they provided care. [That’s] because not all people provide a high-level response in a way that’s practical and tangible to family caregivers and families who are living through the journey.

Those comments and those recommendations gave me the fuel that I needed to expand the knowledge that I’ve gained, that I’m still gaining, and to put it into practical circumstances.

Being Patient: How old was your grandmother when she was diagnosed, and were you noticing signs earlier?

Smith: She developed it later on in life. She was in her late 80s and early 90s, but I didn’t notice anything because I wasn’t there every day or even every week. I would probably go and see her once a month. [I saw more] depression than dementia, and for those who don’t know the difference, they could get those two confused.

It wasn’t until my sister called me while I was sitting at my desk at the disabilities agency and said, “Grandma is walking to people’s houses, knocking on their doors, trying to figure out how to get home.”

My heart dropped into the pit of my stomach immediately because, in the back of my mind, I knew what it could possibly have been, but in the front of my mind, I’m in denial. “It absolutely is not because I was just there a month ago, and I didn’t see anything.”

Because I knew enough about the disease process, once I got over that initial shock and the initial denial piece, I knew it was time to get to work. She would actually develop urinary tract infections a lot, which looks just like late-stage dementia, which it wasn’t. With her, it was a combination of depression and dementia, and then just societal factors and environmental factors, moving from one place to the next and dealing with family concerns.

“Because I knew enough about the

disease process, once I got over that

initial shock and the initial denial piece,

I knew it was time to get to work.”

People don’t realize when you do develop a form of dementia, if the other parts of your life are not healthy, it is going to cause the disease process to progress a lot faster. In her case, it did. She was dealing with depression. She was dealing with the inability to maintain her own home, being a natural environment.

She was staying with my dad. She didn’t want to stay with my dad. It’s just a lot of factors that went into play in terms of her dementia diagnosis and her cognitive impairment. Everybody is different, but I did use a lot of the skills that I had in my professional capacity to help manage her care. I managed her medications.

I was more so the caregiver from [a] distance. I would manage her doctor’s appointments [and] her medications. I would provide support to my dad and my siblings whenever she started with some behavioral challenges, and just navigating what those behavioral causes could be and putting different supports in place to try to mitigate some of the angst and the agitation that comes along with the process.

But of course, they told me to come down there and do it too. I had to go down and spend time with her. That’s almost like the thing that we call an industry rescuing because my dad and my sister were there all the time. When I came in, I was like a breath of fresh air. She could talk about them all day long, and I would be agreeing with her. So, that was like a release for her.

I’ve learned over the years, and being able to share [this] with my families, is [it] really [is] all about the moments in which they are able to lucidly have a conversation with you or share something meaningful. It’s meaningful for both the caregiver and the person living with dementia.

Being Patient: How did the experience with your grandmother’s dementia inspire you to specialize in gerontology as a social worker?

Smith: During that time, about 15 years ago, I didn’t know that I could get a certification in gerontology. I knew what a geriatrician was, which is a medical doctor. Even though I act like a medical doctor, I am not one. I have a [doctorate] in higher education. I got my certification through the National Association of Social Workers.

When I learned that was a certification area, I jumped for joy, because this was my lane. I enjoyed working with the senior population and the disabled population, giving them a voice, and helping people to understand that it’s more about their abilities than their disabilities. That gave me a sense of empowerment. It helped me more to help them than anything in the world.

Of course, it’s not a very lucrative job, but it’s just a person’s life that’s positively impacted and gives you a feeling that money could never provide. I was gaining additional research in the area of Alzheimer’s and progressive types of dementia, learning that there are over 100 types of dementia. Then in that research, [I learned] that there was a certification that I could actually receive to be able to expand on the work that I was doing only locally, that was exciting.

There is a lot of jargon that’s being used in professional terminology that goes over people’s heads, even in a doctor’s office. I just refuse, not on my watch, for someone to remain in a crisis when they don’t have to. I feel like my job, role, and passion point really is to break down those complex ideas into basic, tangible, relatable items of interest.

Being Patient: In your work, what disparities have you noticed in the Black community for dementia care? What is lacking right now, and what can we do about it?

Smith: We talk about the social determinants of health in general that really play an important role in our livelihood and in the way that we live. I’ve gone into hundreds of assisted living communities, and I specifically remember someone saying to me that more white people were at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease than Black people. I said, “Well, the data does not bear that out. That’s actually incorrect.” I asked, “Why do you say that?” They said, “Because there are more white people in assisted living communities than Black people.”

I said, “You’re right, but let’s look at that. Whenever you see that, to determine what the real disparity is, follow the money.” When you follow the funding source, you realize that is why there are more white people in assisted living than, say, Black Americans, because that is private pay.

We [need to] look at the disparities across the board. When we start to assess food, we see food deserts. Food deserts are predominantly in Black communities. When we look at the water we drink and the air we breathe— where there are pollutants in water, and the air is highly saturated with dangerous chemicals, that is in predominantly black communities, not necessarily rural because it could be in the city and the suburban areas as well.

When we look at health deserts and hospital deserts, they’re predominantly in Black communities. You have the food you eat, the air you breathe, the water you drink, and the inability to access appropriate health care. These four factors increase one’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and progressive types of dementia.

With those factors and those elements alone, if you can’t change where you live because of money and financial resources, at least you can have the education. Now, we’re dealing with broadband deserts. Those are in those rural, desolate communities where we find a large amount of Black and brown people live.

“If you can’t change where you live because

of money and financial resources, at

least you can have the education.”

Number one, break down the practices, break down the elements of complex ideas. Then, [diversify] the way in which you disseminate the information. It can’t just be on social media. You need all that information. You gotta do print, you gotta do television, you gotta do radio, and I am on all those platforms, but I can’t be on it alone.

I’m so thankful for what you all are doing at Being Patient, because you have print, you’re on social media, and so you’re providing information and bringing experts in to be able to break down these complex ideas to provide people with real-world, real-time information that they can use that day to change the course of their life, and just being in not just one space, but being in all spaces.

Being Patient: Are there stigmas around Alzheimer’s disease in the Black community? Do you find that the community lacks education about the disease compared to other population segments?

Smith: There is a lack of information, but that could be twofold. Maybe they don’t have access to the information, or maybe they don’t want access to the information. When we talk about just the caregiving experience, that’s going to be lack of access. I was taught that Alzheimer’s was a part of aging. Everybody’s going to get a touch of it. Well, that’s all wrong. One thing that’s right about it— age is the number one risk factor, but that doesn’t mean that you automatically are going to get it because you’re aging.

You can’t have a little bit of it because you can’t be a little bit pregnant, so you can’t have a little bit of dementia. You either have it or you don’t. Then, there are treatable causes of dementia, meaning medication side effects or interactions, lack of sleep, and diabetes. These things are not explained to us as we’re growing up. The reason it’s not explained to us is because our elders don’t have that information. It all boils down to a lack of information.

“These things are not explained to us

as we’re growing up. The reason it’s not

explained to us is because our elders

don’t have that information.”

Number two, culturally, Black people are very keen on taking care of their own. That is shifting a bit as the generations age. We take care of our own, number one, because of being risk averse. We’re not allowing people into our home, getting into our business. We can handle our own. We are a strong Black race. We have to be strong. We have to be resilient. We have to be dedicated.

What we don’t realize is that all that resilience, all that “I can do it myself”— it’s weighing on your body and your emotional psyche. What we know now is that approximately 35 percent of caregivers pass away before the person with the chronic illness.

We do have to have a culture shift, but that culture shift will come with information, not only the information [but also] the provider of the information. Black people tend to take certain information from the Black person who’s delivering the information. If you came into my church, Mark, talking about Black caregiving, they’re not going to listen to you, because how do you know? Same thing with the Hispanic community. How can you tell me about my community when you’re not a member of my community?

“Typically, when it comes to paying for

long-term care, assisted living, or

someone to come into the home,

Black Americans can’t afford it.”

Even though I’m in all communities, and I speak a universal language, if I need to break it down to my Black Americans, I’m going to break it down because I experience it, I know it, and I research it. Those are some of the factors.

[You] want to keep in mind that back in the day, the families were a lot bigger, so you had a lot of natural support to pull from to keep your loved one at home. Families are a lot smaller. I had my daughter when I was 31. I only have one and don’t plan on having another one. Families are a lot smaller.

Then, just going back to the lack of finances, when we look at the disparities in the economics of our country, and then [break] it down into the communities, some of the poorest communities are the Black communities.

We’re not monolithic at all. All Black people are not poor by a long shot. We do very well, but when you look at the disparity, the data, and where there’s economic growth, there’s not a lot of us. Typically, when it comes to paying for long term care, assisted living, or someone to come into the home, Black Americans can’t afford it.

Being Patient: What do you hope people take away from your most recent book?

Smith: Number one, if it’s a family caregiver, if it’s a practitioner, if it’s anybody who is currently providing care support to someone with Alzheimer’s or dementia, or you think you may be in line to provide care for someone— I want this book to serve as a planning guide for you.

I want this book to serve as a preparation guide for you. I want this book to serve as hope and also help. A lot of times when you don’t have the information, because there’s so much information all over the place, and it doesn’t apply to you— you feel helpless [and] you feel hopeless. When you lose hope, you lose life. I don’t want that to happen to anyone under the sound of my voice.

This book is not big at all. It’s very compact. You can read it in a couple of hours, but you’re going to refer back to it as new experiences and situations arise.

Katy Koop is a writer and theater artist in Raleigh, NC.