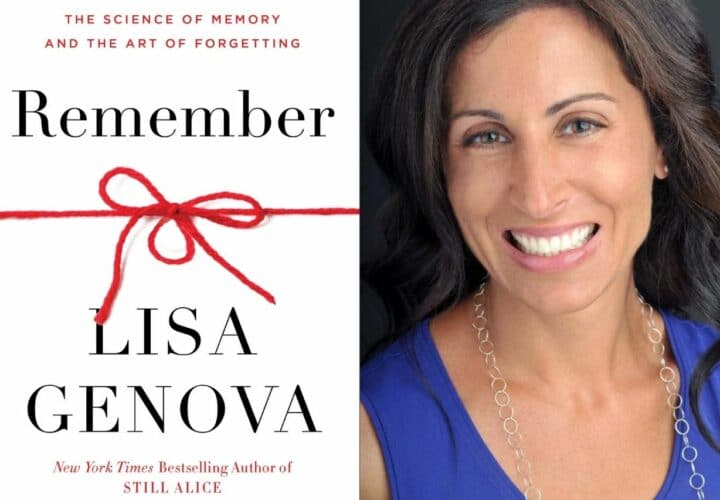

To understand memory, we must understand the power and vulnerability of the brain. In Being Patient's LiveTalk series, Lisa Genova, neuroscientist and author of Remember, shares insight into how our memory works — along with day-to-day strategies for strengthening our ability to remember.

Whether it’s forgetting a name or where we placed our keys and cell phone, memory lapses can be especially worrying for aging adults with a family history of Alzheimer’s: What if this moment is a sign of dementia, foreshadowing more severe memory loss down the road?

But, as neuroscientist Lisa Genova writes in her book Remember, “Our brains aren’t designed to remember people’s names, to do something later, or to catalog everything we encounter. These imperfections are simply the factory settings. Even in the smartest of heads, memory is fallible.”

Forgetting doesn’t necessarily reflect the beginnings of a disease like Alzheimer’s, Genova says, and without paying attention to familiar and mundane routines, our memories of these events tend to go by the wayside. Most of us won’t remember what we wore or what we had for dinner last Monday, let alone a year ago. In fact, as she explains in her book, the majority of us forget most of our life experiences: That’s a normal part of being human, and there’s a fine line between normal forgetting and memory impairment in Alzheimer’s.

“Our brains aren’t designed to remember people’s names,

to do something later, or to catalog everything we

encounter. These imperfections are simply the factory

settings. Even in the smartest of heads, memory is fallible.”

Instead of viewing forgetfulness as our “moral adversary,” Genova hopes we can develop a better relationship with our memory, by setting informed expectations and taking simple, everyday steps to improve our ability to remember. By doing so, “we don’t have to fear it anymore,” she writes of memory. “And that can be life changing.”

Being Patient spoke with Genova, who is also the author of Still Alice, about the strengths and limitations of our cognitive function, and what we can do to enhance our memory.

Being Patient: What question should we ask ourselves to answer whether our forgetfulness is due to normal aging or Alzheimer’s?

Lisa Genova: I think that a lot of us don’t understand memory and that it’s actually quite fallible. It’s not designed to be perfect and remember everything. After the age of 50 or if you have a mom with Alzheimer’s, you start framing everything as all forgetting equals: “I’m going to get Alzheimer’s or this is a prelude to the path to dementia.” What I want people to come away with is understanding what’s normal: “Let’s look under the hood and understand how memory works so that I can know what’s going on when I walk into a room and I don’t know why I’m in there, or I’ve got a word stuck on the tip of my tongue.”

I know that Alzheimer’s is terrifying, but normal forgetting shouldn’t be … I would love for folks to start to get comfortable with the idea of being in conversation about brain health: “How can I influence it? What are the kinds of things that can maintain brain healthy habits today so that I can prevent Alzheimer’s tomorrow?”

Being Patient: Why is paying attention important for memory?

Lisa Genova: Every day, most of us probably have a moment of, “Where did I put my glasses? Where did I leave my phone? Where are my keys? Where’s my coat? Where did I park my car?” Then people instantly go, “I have the worst memory. I think I’m getting Alzheimer’s. I cannot remember where I put my things all day long.”

Here’s the deal folks: Your memory was never even involved, I’m betting, because the number one ingredient in forming a memory that’s going to last longer than right now is your attention … Your memory is not a video camera and it is not a stenographer. It does not record a constant stream of every sight and sound, smell and emotion you’re exposed to. It can only have a chance at capturing what you pay attention to.

Being Patient: Say I put my glasses down and tell myself, “My glasses are on the table.” What happens in our brain in terms of memory formation?

Lisa Genova: You’ve now given your hippocampus a chance to remember it. You need that neural input of your attention. We don’t pay attention to what we already know, what’s familiar and ho-hum and boring. We pay attention to what’s new and surprising and emotional and meaningful … I regularly drive over this four-lane bridge. It’s huge and I will be 10 minutes past this bridge and think, “Wait, where am I? Did I already go over the bridge?”

I can’t recall going over this bridge that my eyes were available to. My brain saw the bridge. I didn’t go over with my eyes shut. My brain got the visual information. My muscle memory — my memory to the choreography of how to drive — was online. I didn’t crash into anything. But my brain has no memory of driving over the bridge because I didn’t pay attention to anything about the bridge even though I saw it. We can’t remember what we don’t pay attention to.

“Your memory is not a video camera and it is not a stenographer.

It does not record a constant stream of every sight and sound,

smell and emotion you’re exposed to. It can only have a

chance at capturing what you pay attention to.”

Being Patient: So we forget most events in our lives?

Lisa Genova: You will very normally forget most of your life. Most of our waking hours are actually spent doing routine, ho-hum, been there done that things. Tell me everyone you texted three days ago. Tell me what you had for lunch last Thursday. Tell me what you wore last Wednesday.

Being Patient: I have no idea.

Lisa Genova: This is why we remember vacations. [We’ve] gone to a new city [with] new architecture and different meals and different culture. We’ve taken photos of it. We post [the photos] to social media so we can revisit [them] with captions. It’s like a photo album that we keep going over and it’s probably emotional because we [were with] other family and maybe it was wonderful, or maybe we fought. It’s not same old same old. There’s lots of feeling and newness and repetition.

“Every time we learn something new, we can build

new neural connections, so we can build more branches

to connect neuron A to B to C to D. But we also birth

new neurons throughout life. It’s called neurogenesis.”

Our brains are not designed to remember to do something later (prospective memory). There’s a lot of folks out there that think, “If I can’t remember a name, [and] I Google it, I’m cheating and I’m going to make my memory worse.” No, you can Google it. It’s okay. By the way, then that frees up your brain to learn and think and pay attention to other things. If you’re constantly like, “What’s his name? What’s his name? What’s his name?” you’re gonna drive yourself nuts … If you need to pick up milk at the grocery store later, put it in your phone, write it down, or you’ll probably forget the milk.

People think, “No, I shouldn’t. I should remember it. I should try harder.” No, it’s not gonna make your memory for all the other stuff better and you’re probably gonna forget. Airline pilots do not rely on their brains and their prospective memories to remember to lower the wheels of the plane before landing them. They use checklists. You outsource your prospective memory.

Being Patient: You wrote about a group of people with highly superior autobiographical memory (HSAM). Can you share with us more about what makes them unique?

Lisa Genova: About 100 people have been identified and one of them is actress Marylu Henner.

There’s three kinds of long-term memory. There’s the memory for the stuff you know. That’s semantic memory, all the facts and information you learned in school. Six times six is 36. George Washington was the first president. It’s your address and phone number and date of birth, all of that info.

There’s also muscle memory. It doesn’t live in your muscles. This is the memory for the choreography of how to do things: how to brush your teeth, ride a bike, drive your car, hit a tennis ball, type. That muscle memory is in your motor cortex motor. The desire to move and the choreography to move is in your motor cortex. Those neurons go to the spinal cord, and then to every voluntary muscle in your body. Your brain tells your body what to do.

The last kind of long-term memory is called episodic, and this is the memory for what happened. That’s what highly superior autobiographical memory folks have. They can remember what happened on pretty much every day of their lives from around age 10 or 12 on.

Being Patient: What happens to our ability to remember in old age?

Lisa Genova: What you’re going to feel as you age is processing speed slows. Retrieving what you already know feels slower, but your memories for what happened are just as accurate and inaccurate as your younger counterparts. You will have trouble paying attention to more than one unrelated thing at a time as you age. If you’re trying to do that, you’re going to remember less of it, because you’re not able to attend as well.

Otherwise, as we age, we accumulate wisdom, which is the memories for what happened and the memories of the stuff you know.

Being Patient: Aside from paying attention and writing things down, what are other strategies that could improve our ability to remember as we age?

Lisa Genova: Akira Haraguchi was a retired engineer in Japan who decided he wanted to memorize pi to as many digits as he could. He memorized the non-repeating patternless numbers to over 111,000 digits at age 69. He’s not a mathematical genius. He’s not a savant. He used what all of these memory champions use, which is understanding our memory system’s love of story — because stories are meaningful — emotion, things that are surprising and weird and bizarre. Each number is attached to an image or a word and it tells a story so they don’t just rotely memorize all of those numbers.

If I want to remember to buy milk and I didn’t write it down, my memory retrieval is best served if I attach something to that. Our brains love things that are visual, weird, surprising [and] where things are in space … If I want to remember milk, I can imagine Dwayne The Rock Johnson milking a cow on my kitchen table. Now I’m going to remember to buy the milk … If we add meaning and story to what we’re trying to remember, that helps us our brains a ton, Our brains love that.

“A lot of us don’t understand memory

and that it’s actually quite fallible.

It’s not designed to be perfect

and remember everything.”

Being Patient: Can new neurons grow in our brains?

Lisa Genova: Every time we learn something new, we can build new neural connections, so we can build more branches to connect neuron A to B to C to D. But we also birth new neurons throughout life. It’s called neurogenesis. We can make new neurons. When I was in graduate school in the 90s, we were told, “No, you never birth new neurons after you’re born.” But that’s been debunked.

You don’t birth new neurons everywhere in your brain, but one of the places that this happens throughout life is your hippocampus, which is great news, because this is the engine that allows us to knit together the sights, the sounds, the smells, the emotions, the information that is a memory. The hippocampus is required to take previously unrelated information or new information and bind it together so that we can then recall it again later.

We can increase the neurogenesis in our hippocampus, which is increasing the size and the robustness and the power of this part of our brain, through aerobic exercise. We think it’s about 30 minutes a day for four to five days a week. A brisk walk, which means walking like you’re in a hurry, can do it. We know that meditating can increase the size of your hippocampus.

We know that for people who have two copies of ApoE4 — a genetic risk of Alzheimer’s [which] doesn’t mean you’re gonna get Alzheimer’s but you’ve got a much higher chance of developing it — your hippocampus will be smaller than someone who does not have two copies of ApoE4 only if you’re sedentary. If you have two copies of ApoE4 and you are an exerciser, your hippocampus will not be smaller.

People think, from the neck up for some reason, it’s not part of the rest of the body. It is folks. You know you have an influence over your heart health. I know you guys believe this at this point. We count our steps. We know the kinds of food that support heart health. We know that blood pressure is a measure of heart health. We monitor and influence our heart health and we’re comfortable with that. You can do that with your brain as well.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.