This article is part of the series Diversity & Dementia, produced by Being Patient with support provided by Eisai.

Henrietta Lacks. The Tuskegee Experiment. When husband-and-wife team Mollie and Ralph Richards got involved in Alzheimer’s advocacy, one of the biggest obstacles they encountered between Black communities and adequate healthcare access was a lack of trust. They’ve devoted nearly a quarter century to changing that.

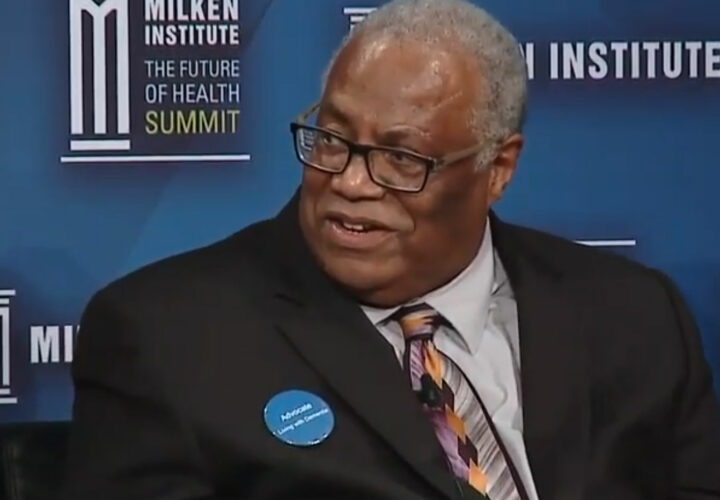

Mollie and Ralph Richards have been doing Alzheimer’s advocacy outreach side by side for a quarter of a century.

Mollie and Ralph Richards have been doing Alzheimer’s advocacy outreach side by side for a quarter of a century.

Ralph has a background in radiology and worked for Eastman Kodak for more than 30 years. When he was invited to become the first Black board member at his local Alzheimer’s Association chapter, he said, he was shocked at how little Alzheimer’s awareness existed among his Black neighbors where he and Mollie were living in Virginia.

“We need to make a difference,” Ralph recalled thinking at the time. “We need do something different.”

Mollie has been involved in Alzheimer’s advocacy right alongside him. Her father was diagnosed with dementia when she was 17 and learned more about Alzheimer’s working as an occupational therapist in long-term care homes. She eventually organized a team of 16 colleagues who were dedicated to educating all the home’s staff about Alzheimer’s.

That team’s work expanded outward, and together, the couple has continued working to make information about Alzheimer’s more accessible. They’ve also been focused on finding ways to encourage the purveyors of Alzheimer’s research — which has historically looked at primarily white participants — to make studies more inclusive and to encourage people of color to enroll in clinical trials.

Improving clinical trial diversity requires building trust

Recently, Mollie and Ralph gave a presentation about Alzheimer’s at her family reunion to about 80 people, most of whom, Mollie said, are African American.

“We talked about the disease, healthy living, and the importance of research,” she told Being Patient. But she fielded a lot of questions from her family when she explained that she’s been a research participant for six years. “It was the same story that still persists in some of the Black communities,” she said. “We don’t trust, we know what they’ve done in the past and they’re going to be experimenting on us.”

She noted that people often bring up the Tuskegee experiment — in which 600 Black men were told they were receiving treatments for syphilis, when in actuality the doctors watched them progress through the disease for 40 years, continuing into the 1970s, despite the availability of safe treatments — and the case of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman in the 1950s whose cervical cells were taken by doctors without her permission, developed and still sold to researchers around the world.

Given the disproportionate number of Black Americans affected by Alzheimer’s, Black representation in clinical trials is essential to understanding the disease — and its possible treatments.

“The medication that Biogen put out [Aduhelm], less than one percent of [clinical trial] participants were people of color,” Mollie pointed out. Consequently, it’s unclear whether the drug is effective in people of color.

But drug developers struggle to boost diverse enrollment. “People don’t understand that all people of color are not the same,” Mollie said. “Some are from Haiti, some are from Africa, some are from the Bronx, and some are from California,” Mollie said.

Importantly, Mollie and Ralph believe that researchers and clinicians also need to play an important role in building trust.

“We advise the researchers how to put together flyers or bookmarks, and how to deal with people that are different,” Ralph said. “Researchers and doctors should understand the community that they’re working with, some of their needs and some of their concerns.”

He reiterated that the Tuskegee experiment still looms in much of the community, and concerns over this kind of experimentation can’t simply be discounted by researchers and clinicians. “You have to say, I understand what you’re saying,” Ralph said. “There has to be a degree of trust, and if you violate that trust in any way, you lose the community.”

Many researchers and doctors still may not be comfortable speaking with African American patients. Even today, many doctors are 2.5 times more likely to include negative descriptors in African Americans like “agitated,” “angry,” “challenging,” or “non-adherent.”

“Researchers don’t seem to be comfortable as a whole, just opening up and talking to us,” Mollie said. “They’re not asking us what we think and what we feel about things.”

Later in the day, Ralph added, the couple will be having a luncheon with a local physician and their wife. “We had to work hard to establish that relationship and trust in the community,” he said. And there is still work to do: “Everywhere we go, we’re going to be talking about Alzheimer’s.”