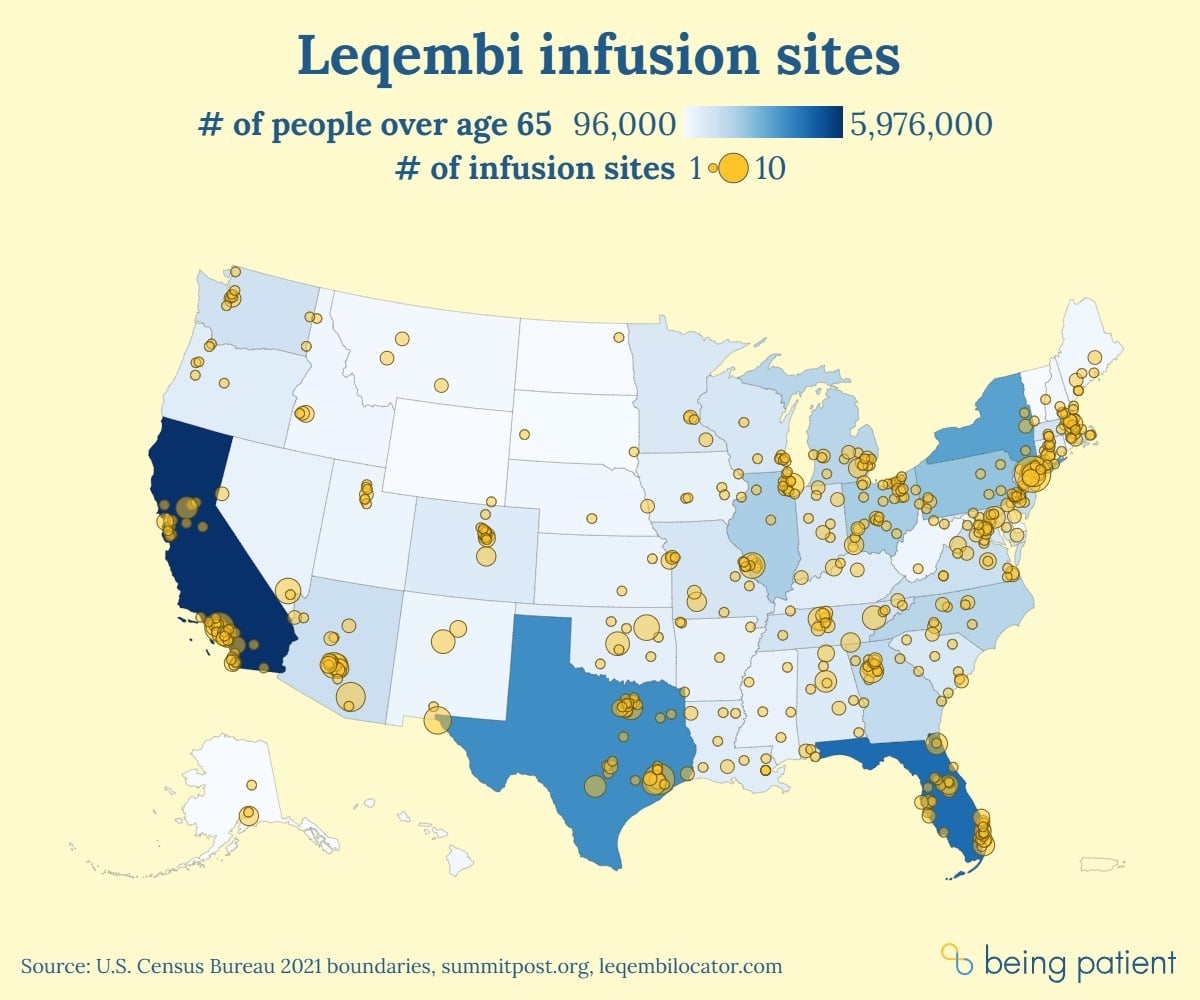

We mapped drug infusion centers across the U.S. and found that capacity for distributing new Alzheimer’s drugs is lacking. In some of the counties with the nation’s highest Alzheimer’s prevalence, patients must drive hours to get new disease-modifying treatment.

Diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and one of the relative few who has gotten a prescription for the new, disease-modifying anti-amyloid drug Leqembi? If you live in one of the counties with the highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s, you may need to travel upwards of 100 miles every two weeks to receive the treatment — and the cost of traveling back and forth to drug administration sites is not covered by Medicare.

Being Patient looked at the number of infusion sites near the 10 highest- prevalence counties for Alzheimer’s in the U.S. In these counties, more than one in six people over 65 have Alzheimer’s disease. Two of these counties — Dougherty County, in Georgia, which is predominantly Black, and Imperial County, California where residents are predominantly Hispanic — have zero infusion sites that can administer Leqembi, the only disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer’s.

And in half of these “Alzheimer’s hotspot” counties, there are no infusion sites within 10 miles of the geographic county center. Six have fewer than 10 infusion sites within a 50-mile radius.

In multiple U.S. states, Leqembi access is very limited

Our analysis found that patients in the communities that need treatments like Leqembi most may have to drive long distances to access the drug. And experts say there may not be enough infusion centers in the country to treat eligible patients.

Jim Taylor, president and CEO of the advocacy group Voices of Alzheimer’s, told Being Patient many patients need to travel great distances for these infusions. “Travel time will need to be a factor in the decision to take the drug,” he said.

Being Patient took a look at the distribution of sites where patients can access the drug — and even for a team of reporters, finding out where a patient could get Leqembi wasn’t easy.

The National Infusion Center Association declined to share the locations of all infusion clinics offering Leqembi with Being Patient. Looking up the nation’s highest-prevalence counties in Leqembi Locator — a site developed by the National Infusion Center Association — we developed an estimate of how many infusion centers are offering Leqembi in these areas. Using this tool to review site locations state by state, Being Patient estimated there are a total of 853 infusion sites in the country offering Leqembi.

Eleven states had five or fewer infusion sites listed:

- Delaware

- Mississippi

- Arkansas

- Nebraska

- West Virginia

- Rhode Island

- South Dakota

- North Dakota

- Vermont

- Wyoming

- Hawaii

Meanwhile, despite being the third-least populous state and containing no Alzheimer’s hotspots, Alaska has six infusion sites — more than Mississippi which has about eight times as many seniors living with Alzheimer’s disease.

According to Libby Holman, a spokesperson from Leqembi’s drugmaker Eisai, people living in southwest Oregon, the Chicago Metro area, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia are also calling into the company saying they are having trouble finding infusion centers with capacity to treat them.

While there are infusion sites within the most populous Georgia counties (Fulton, Gwinnett, Cobb, DeKalb, and Clayton) and the Chicago Metro area, there are no infusion sites within a 50-mile radius of the most populous counties in Southwest Oregon., meaning that people in Southwest Oregon need to drive over 50 miles for treatment.

There are fewer than five sites within a 50-mile radius of the most populous counties in North Carolina. Are a couple centers enough to meet capacity? Experts say it’s hard to guess, as the size, and scope of services of these centers varies.

Based on estimates from a 2019 study, there were 910,000 adults over the age of 65 newly diagnosed with Alzheimer’s as of 2011. A 2023 study estimated that about 8 percent of people with early Alzheimer’s disease quality for Leqembi.

If the estimates from 2011 remain constant, there may be 72,800 people who qualify, meaning each infusion center would need to service 85 patients.

To Tracy Meinke, a spokesperson for AleraCare, which operates 35 infusion centers across six states, that sounds like a lot. Meinke told Being Patient that they currently have 100 patients on Leqembi across all 35 centers, and that there is intensive clinical and care coordination involved in getting a Leqembi patient approved, treated, and maintaining their treatments.

“The clinical workflow required to manage Leqembi is highly complex, labor intensive, and time consuming,” she said. “Of all the 100+ drugs that AleraCare administers this drug has the most challenges and demands the most resources.”

As a result, Meinke added, infusion centers incur higher costs for administering Leqembi to patients than they incur from other infusion-based drugs.

While there are a handful of infusion centers specializing in Alzheimer’s or neurological diseases who can treat more than 100 patients, smaller clinics which make up the majority of these infusion centers, have a much smaller capacity.

Dr. Erik Musiek, at Washington University in St. Louis says that the infusion capacity of a center can differ a lot depending on size. The neurology center where he works was one of the first in the country to offer Leqembi infusions to patients.

“Our center has over 100 people on lecanemab at this time, and it is very taxing — and we have numerous physicians, nurse practitioners, and other full time staff working on it,” said Musiek. “Certainly there are many people, particularly in rural and underserved areas, that do not live near any of these things, and that is a major challenge.”

Accessibility is a bigger issue than infusion centers

There are many other reasons that patients might not get access to Leqembi or any other new anti-amyloid Alzheimer’s drugs that make it onto the market in the near future. One issue, according to Aranda, is that people aren’t getting timely information because there are so few geriatrically-trained social workers who specialize in dementia care.

“For communities that are low-resourced and have low levels of information regarding dementia, where to go for help, and availability of infusion centers nearby, you have the perfect storm of lack of equitable access to treatment, resources and support for people and families living with Alzheimer’s disease,” Maria Aranda, a professor at the University of Southern California told Being Patient.

“These social workers are key in providing timely and accurate information” about things like memory loss, brain health, and treatment planning, Aranda said.

There’s a shortage of other Alzheimer’s experts as well.

Americans are finding themselves unable to get a diagnosis due to a shortage of neurologists and other clinicians that can diagnose Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

According to Musiek, these specialists also need to obtain and interpret biomarkers and ApoE genotyping, and have access to radiologists that can monitor patients for brain swelling and bleeding, a side effect of anti-amyloid drugs called ARIA.

“It takes a lot of infrastructure that is not available [in] many places, even large academic centers often do not have all of this in place,” Musiek said.

Then, for Alzheimer’s patients who are diagnosed at the early stages and are prescribed Leqembi or other anti-amyloid drugs in the future, “time is brain” Dr. David Weisman, a neurologist at Abington Neurological Associates who treats patients with Leqembi, told Being Patient. He added that when treatment is delayed for months, it could mean that patients may progress to the point where they’re no longer able to take the drug.

Future monoclonal antibody drugs for Alzheimer’s — future access woes?

While Leqembi is approved, many neurologists and researchers are still debating whether the effects of the medication are meaningful for patients. New monoclonal antibodies that target amyloid, tau, or microglia may come onto the market in the future — even if the benefits of these newer drugs are much greater — there may not be enough infusion sites to deliver these treatments.

Drugmakers are now developing injectable forms of anti-amyloid antibodies like Leqembi or donanemab which could be administered at home. However, it is currently unclear when these formulations might hit the market — and how widely they’ll be distributed, or how easily they’ll be made available to patients, when they do.

UPDATE May 2, 2024 4:08PM: Corrected the number of Leqembi infusion sites in the US — from 836 to 853.

This was an interesting article. I am on Leqembi and notice there administratively lots of time spent talking with Eisai, the Japanese manufacturer of Leqembi, have organized a “patient support person” who organizes when doses of this medication is mailed from their pharmacy in Texas (to the infusion center in thermal…….you cut off the rest of my comment

We’re so sorry your comment got cut off. We’re looking into that. In the meantime, please feel free to email comments to info@beingpatient.com with your comment as we’re really interested to hear about your experience on Leqembi. And thanks for reading!

As a very lucky patient receiving Leqembi thank you for letting others know. I was fortunate although it did take many years to get a diagnosis to be at a hospital that made it available. I hope many more can receive as well

Thank you for sharing your experience with Leqembi. Wishing you the very best with your results, Michael. Take care!

Interesting article. My husband was diagnosed last October with early stage Alzheimer’s. I have tried every avenue possible to have him treated with Luquembi. Everything you stated in your article is true- lack of availability, not enough doctors knowledge of the drug, lack of infusion centers and medical professionals. If has been an incredibly frustrating experience.

As an aside, we are well educated, have access to good health care and have some connections in tge health care field. Heaven help those with fewer resources.

Hi Ellen, we’re sorry to hear about your husband’s diagnosis and the challenges you’re facing. We hope that increased awareness and advocacy will lead to better Leqembi access for individuals in the future. Thank you for sharing your experience and being part of our community.