Phil Gutis, a reporter and Being Patient columnist living with early-onset Alzheimer’s, reflects on his years of marathon running — and how, when it comes to brain health, they may still be paying off.

It was 1999. We were about to turn the clock on a century and a millennium. I don’t remember how it all exactly happened, but apparently thought it would be a good idea to mark the new year by deciding to become a runner. And because I never do anything halfway, I decided to begin my running adventure by training for a marathon.

My first and second official races were the Marine Corps Marathons in Washington, D.C. I ran them to raise money for AIDS research and support. Even though the training was grueling, I completed both races and found myself captured by a bit of a running bug.

Friends and I decided it would be “fun” to pick a marathon somewhere in the country and fly out for the race. It was at one of those random races that I met an amazing woman named Cathy Troisi. I don’t recall how we started chatting but I remember that Cathy was an “older” woman (older than me anyway — she was only probably in her early 50s at the time) but she told me that she too was a late-in-life runner, and that she traveled around the country to run marathons. She added that she often ran a marathon every weekend.

Inspired by Cathy’s crazy schedule, I decided that if she could run a marathon every week, I could do one every month for at least a year. The dates and races are lost to my memory, but I distinctly recall running a marathon a month for six months.

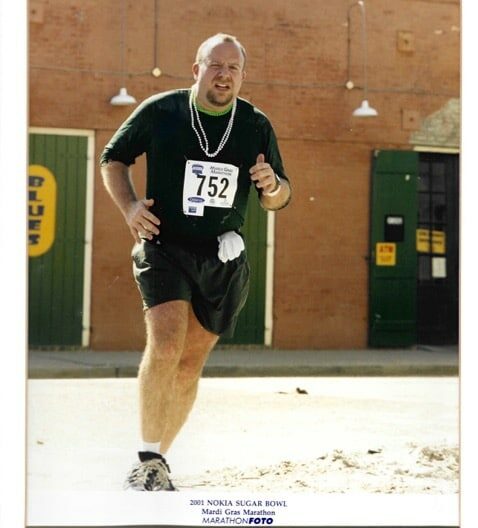

Over my short running career, I did marathons in Washington, New York City, Philadelphia, Virginia Beach and Disney World (the Mickey Mouse medal is awesome! In fact, I had to go back the next year to run the half-marathon to get the Donald Duck finishers medal). I also completed marathons in Oklahoma City, New Orleans, Hartford, Huntsville, Alabama, Madison, Wisconsin, and Clearwater, Florida.

Over a three-year period, I went the 26.2-mile distance 17 times.

I was in San Francisco, running my seventh monthly marathon of the year, when my quest ended. I had just crossed the half-marathon line and saw a bus there to take the 13.1-mile finishers back to the start of the race. I made the hasty decision that I had had enough and hopped on the bus, accepted my half-marathon finishers medal and crawled to a seat.

I was done. I don’t believe I ran another step for ten years or more. That’s not to say that I didn’t exercise — but more about that in a bit.

I just saw on Facebook that Cathy passed away unexpectedly at age 76. In addition to memorializing a friend and marking her incredible achievement – 400 marathons run and hundreds of thousands of dollars raised for cancer research – I wanted to write this piece because I’ve been thinking once again about exercise and the role that movement has on development and progression of cognitive diseases.

Exercise and I have long had a love-hate relationship — heavy on the hate. I didn’t participate in sports while growing up, and I’ve always struggled with my weight. (Even while running those marathons, I would weigh in at around 200 pounds on my 5’7’’ frame.)

That midlife jolt, however, got me moving. While I still see myself as a sedentary being (the COVID years didn’t help), I’ve been fairly athletic. I’ve done two Climate Rides, where we biked more than 100 miles a day. I dabbled in CrossFit for several years and had developed an awesome rowing routine at an indoor rowing studio.

COVID, however, destroyed my routine. The rowing studio closed and I’ve not been able to motivate myself to find a replacement. And, of course, my type 2 diabetes came roaring back and my blood pressure has become challenging again. Lately, I struggle to work exercise into my daily routine.

I recognize that I need to get moving again, and my friend Brittany Cassin — co-founder of a brain health company that works in artificial intelligence and Alzheimer’s early detection — and I are working on a brain health action program that we hope will lead to running a marathon. We’ve got a long way to go. She’s walking about three miles; I’ve been doing about a mile — and I’m exhausted afterwards.

While the research is clear about the connection between exercise and cognitive disease, I wonder why my 20-some years of intense exercise didn’t stop me from developing Alzheimer’s. But then again, my progression has been very slow.

I generally attribute this slow progression to receiving Aduhelm as part of an ongoing clinical trial. But there’s another possibility: What if my Alzheimer’s has progressed relatively slowly because I did all that exercise in my 40s and 50s?

Or, what if the reverse is true: All those miles, all that Crossfit activity and endless rowing did nothing to stop the appearance of Alzheimer’s.

It is a frustrating thought to consider. And we may never know the answer: There’s so much still unknown about Alzheimer’s and other cognitive diseases and the brain is the most complex organ in our body. Hell, the only way to conclusively determine the cause of cognitive illness is a post-mortem brain autopsy.

Still, though, inspired by my friend Cathy and with Brittany’s assistance, I pledge to get active again. Exercise will not cure my Alzheimer’s but just perhaps it will help slow down the progression. I’m sure I’ll be writing more about my efforts. So stay tuned and wish me luck!

Phil Gutis is a former New York Times reporter and current Being Patient contributor who was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s. This article is part of his Phil’s Journal series, chronicling his experience living with Alzheimer’s and his participation in the aducanumab clinical trial.