Parkinson’s advocate Benjamin Stecher and neurologist Dr. Alfonso Fasano share a real-life experience of neuromodulation technology and talk about their upcoming book, 'Reprogramming the Brain.'

High-tech treatments for neurodegenerative diseases aren’t so far off. In fact, some patients already have brain implants that help address their symptoms by sending electrical signals to different parts of their brains. One such example is Benjamin Stecher — a speaker, author, and Parkinson’s Disease advocate who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at age 29. In 2021, Stecher decided, in collaboration with his neurologist Dr. Alfonso Fasano, to undergo the implantation of two six-inch-long metal alloy spikes all the way through his brain. He now has a battery in his chest and wires that run up to his neck — all of which work to provide a therapy called adaptive deep brain stimulation (DBS), which Stecher says has has almost “wiped away” many of his Parkinson’s symptoms.

“As soon as Alfonso turned on this DBS for me for the first time,” Stecher recalled, “I felt like the whole world had been lifted off my shoulders.”

“As soon as Alfonso turned on this DBS for me

for the first time, I felt like the whole

world had been lifted off my shoulders.”

In the new book Reprogramming the Brain (Springer, March 2024), co-authored by this patient-and-doctor team, Stecher and Fasano trace their decision to pursue adaptive deep brain stimulation and provide guidance on the future of neuromodulation. They joined Being Patient founder Deborah Kan to discuss neuromodulation, their experience with the process, and the future of treatments like these. Read or watch the whole conversation below to learn the story behind this innovative new treatment for Parkinson’s.

Being Patient: What is neuromodulation?

Dr. Alfonso Fasano: Neuromodulation is just a general term that we use to modulate the activity of tissues like neurons. As people probably know, neurons use electricity to communicate with each other, and they’re like electric wires. So, most neural modulation techniques are indeed using electricity delivered in different ways to modulate the action of neurons.

Being Patient: Does neuromodulation require a physical implant in the brain?

Fasano: There are different ways. There are invasive and non-invasive forms of neuromodulation. The invasive ones are treatments like vagal nerve stimulation, spinal cord stimulation, and, indeed, deep brain stimulation, which is what Ben and I can focus on.

Non-invasive ways are techniques like TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation, DCS, and there are many others. They [are] appealing to some extent because they can neuromodulate without an implant. The downside of these approaches is that they don’t lead to permanent effects because, of course, after the neuromodulation is removed from the body, then the effect, little by little, goes away.

These are still useful in rehabilitation settings, or to explore new targets for the future. So, these new targets will be then treated with invasive treatments.

Being Patient: Benjamin, you were first diagnosed at 29 years old, and it’s been a decade since then. Can you tell us about the early symptoms and then how you found out about neuromodulation?

Benjamin Stecher: My first symptoms were a tremor, my right hand slowly progressed, as well as some bradykinesia as well, and some slowness of movement that I was experiencing. Those progressed, and I got to the point where I realized how much trouble I was in.

I then came back home from China, where I was working at the time. I found Dr. Fasano’s clinic, and he was the one who really introduced me to not only neuromodulation, but this whole world of Parkinson’s research.

From there, I kind of took off and I explored the world. I traveled all over the place to see who had the best solutions for [someone like] me. I found the best solutions out here in Toronto, funnily enough, at his clinic where three years ago, I got this new type of deep brain stimulator implanted in me.

Being Patient: So, you actually got the invasive kind, and they put an implant into your brain. Tell me a little bit about that.

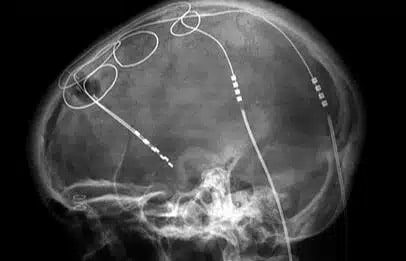

Stecher: I have two burrows [that] have been dug through my skull; six inches or both parts of my brain, there are electrodes. There’s this battery in my chest and wires that [go to] my neck. This is what allows me to live again. Right now, I’m not really on any kind of medication at all.

“I found Dr. Fasano’s clinic, and he was the one

who really introduced me to not only neuromodulation,

but this whole world of Parkinson’s research.”

That’s the result of having done this new type of deep brain stimulation therapy. The kind I have is adaptive. That means it’s actually modulating the signal based on the output that’s coming out from the electrode. We can talk about that more in detail if your listeners are interested. As I said, [it was] about three years ago; it’s powering my life right now.

Being Patient: You had frequent tremors prior to the implants, right? Now that you have the implants, do you have tremors anymore?

Stecher: It’s true, from time to time. Tremors [are] the most obvious symptom of Parkinson’s, but it’s not the one that bothers me the most. The biggest ones are things like dystonia, which is like curling up [and] the spasming of the muscles that patients often experience, bradykinesia, and dyskinesia as well, which is like the involuntary movements that people get.

All three of those have been almost clearly wiped away, because of this new procedure that I had. I still have some mild tremors from time to time, and my walking can be slow, and it’s a little bit impaired— but it’s like night and day compared to where it was beforehand.

Being Patient: That’s amazing. It’s been three years— have the implants have consistently kept your symptoms at bay for the most part?

Stecher: For the most part, yes, but I still have to go back to my clinic from time to time, about every two to three months it looks like right now. It’s for them to make small adjustments [for] some of the settings.

Being Patient: Dr. Fasano, how are the electrical signals modulated in the brain with this type of implant? How does the whole neuromodulation system work?

Fasano: Right now, Ben is coming roughly often for a number of reasons, including the fact that we’re learning still how to better use this technology. Deep brain stimulation has been around for three decades, and it’s been doing a good job, but right now, we are trying to make it even better, and this is when adaptive stimulation might make the difference.

“I still have some mild tremors from time to time,

and my walking can be slow, and it’s a little bit impaired—

but it’s like night and day compared

to where it was beforehand.”

To answer your question, the same electrodes that are implanted in Ben’s brain are able to record the neuronal activity, and we now have a sort of biomarker telling us when Parkinson’s is flaring up. That is called Beta. Beta is a certain frequency that these neurons are firing at.

When that signal is picked up by the stimulator, this is the signal that the stimulator itself wants to reduce. So, based on that, the power of the stimulation will go up and down to reduce the amount of beta to the physiological level because we all have some beta in the brain, but in Parkinson’s, it is more than usual. That’s basically what’s [happening].

Being Patient: Is there a computer or a device that you hook up to to see what is happening? How does that all work?

Fasano: Maybe one part that we should clarify is that Ben showed where the electrodes are, but they’re connected to a battery pack that is placed under his right collarbone. So, it’s a little computer also with a battery. The electrodes are connected to extension wires that run under the skin.

“Deep brain stimulation has been around for three decades,

and it’s been doing a good job, but right now, we are

trying to make it even better, and this is when

adaptive stimulation might make the difference.”

Everything [is] in the body, and in theory, he can go wherever— you can travel. He doesn’t need to be here in Toronto and see me necessarily all the time, and I’m sure he will avoid [seeing] me [sometimes], but it doesn’t have to be physically here for the stimulation to occur. Stimulation occurs all the time.

The reason we meet every once in a while is to adjust the settings because the disease and this is important to stress for the audience, is not a [static] disease; [it is] a disease that tends to change over time. So, we’re trying to modulate the parameters.

The idea is that in the future, it won’t be needed. This particular party won’t be here anymore, because the simulator itself will learn and will adjust even well beyond what we can do automatically right now.

Being Patient: We have a question from our audience for Benjamin. Are you experiencing any side effects from this therapy?

Stecher: There are some weird things. For certain activities that require a lot of bilateral upper and lower body control, like swimming, for example— it’s something I can’t really do anymore. Maybe with proper training, though, and if I got a therapist who specializes in these kinds of things, then that would help me a lot. Right now, that’s one activity that’s kind of off-limits for me.

Being Patient: Why exactly can’t you swim after getting deep brain stimulation therapy?

Stecher: Maybe Alfonso can answer that one as well. From my perspective, it’s like the computer. It’s constantly having to think about, “What do I need? What do I need at a given moment of the day?”

So, if I punch myself into a different environment, the things that I need are very different in that environment than if I’m just walking around living my life. That’s just my perspective. I’m sure there’s something more technical that I’m missing that Alfonso can fill us in on.

Fasano: Maybe we can just clarify because otherwise, people will be concerned that swimming is impossible. It’s way more complicated than that. The stimulation makes sure that movements are fluid and fast enough, but sometimes, for complex motor tasks, what we need is fine coordination within the different groups of muscles between the upper and lower body, as you heard, the right and the left.

The disease doesn’t go away. This is not a cure, unfortunately. This is a treatment. People feel good, as you heard from Ben. In the past, what we’ve seen is that people start going back to anything they used to do 20 years before.

There have been some cases where people unfortunately died because they went to the sea and said, “Okay, now I’m feeling much better, let me go for a swim for half an hour.” There are limits to what we can do. There are also limits to the fact that we are aging. I mean, Ben is young but still is aging, like all of us.

Also, the conditioning plays a big role. Because if for years, you haven’t done much because of a disease, once the disease is under control, it’s not like right away, you can go and do all you want. You need to slowly start and make sure that your overall health is in good control and you’re exercising, which is at the end of the day, really something that can change the future of anybody.

“The disease doesn’t go away. This is not a

cure, unfortunately. This is a treatment.”

But yes, for more fine motor tasks, DBS itself can make things more complicated. This is something we also see in musicians. Maybe they’re looking great and don’t have visible signs of Parkinson’s, but they can tell you that when they try to use their fingers in a more complex fashion, they feel that it’s not as good as it used to be.

Being Patient: What is happening inside the brain of someone with Parkinson’s, and why does deep brain stimulation help the symptoms?

Fasano: Let me just make a little preface to Ben’s answers. Ben has decided to dedicate his life to understanding this disease, and one thing he will tell you is that the more you dig into Parkinson’s, the less you know because it’s a complex syndrome.

It’s not just a single disease coming from different causes, and Ben really has traveled the world, has spoken to, I don’t know [how] many hundreds of researchers in the field. So, he’s the right person to answer what’s going on in Parkinson’s brain.

I just want to say that Ben is an incredible example to everybody out there, not just with Parkinson’s— with any disease, that when you have a diagnosis, it’s your chance to decide whether to be a passive product of what happened to you or decide to take ownership and, and do all you can— [teach] yourself and possibly help others, which is what Ben did.

Being Patient: That’s amazing. Benjamin, from your perspective, what’s going on in your brain?

Stecher: It is, as Alfonso was alluding to, it is a degenerative condition. So suddenly, it’s getting worse and worse over time. However, what exactly is happening is something that’s up for a lot of debate. In my humble opinion, I don’t think anybody’s really qualified to know exactly what’s going on. I think that it’s part of the spectrum of neurodegeneration that we see across Alzheimer’s, dementia, ALS, and FTD to some extent.

There [are] things happening that we just don’t understand very clearly right now, but what is clear and why treatments like DBS work is that there’s a part of our brain that is slowly fading away over time. It seems to be happening in places like the SN, in the substantia nigra, and VTA first, but nobody knows exactly where it begins either.

“Ben has decided to dedicate his life to understanding

this disease, and one thing he will tell you is that the more

you dig into Parkinson’s, the less you

know because it’s a complex syndrome.”

That’s the tricky part about knowing exactly how to treat each individual that comes into a lab. Alfonso was there, and so the question I would love to ask Alfonso, actually. How would you know? Were these clues that DBS was the best therapy for me? And for other patients out there might also be struggling, diagnosed like Parkinson’s, how will they know if this will actually work for them or not?

Fasano: He’s already taking your role, Deborah. Classic Ben. Ben and I just wrote a book describing our experiences and, and how the partnership worked. I can tell you, as challenging as he can be today, for me to write a book with it, but it was also a lot of fun.

I will quickly say that in this book, there is a chapter where Ben talks about the cards that we are dealt, and this is life. We have issues and problems, and then there are also solutions that are offered to us. This is to say that not everybody’s a good candidate for deep brain stimulation, and DBS is not the only treatment. There are many other things, including doing nothing. It’s not that you have to necessarily do something.

But, what’s important is to be aware. So, awareness and good relationship and communication with your care provider is key, because then there’s a best solution that together you get to. When it came to Ben’s case, we were actually debating what was his best solution.

I just need you to realize that it was me, the neurologist, seeing the patient Ben who was meanwhile, [traveling and] spoke with all researchers and knows exactly what’s happening in every lab and knows what’s going to happen in the future, which ones are the trials. Ben knew about stem cell treatments, gene therapy, and all of that.

The reason why we decided to go for DBS in the case of Ben is because it was the treatment already approved, with the highest level of evidence that it will make a difference in terms of quality of life. So, there are certain treatments that are very promising, but because of the lack of certainty, you might not want to go there, especially if your quality of life is suffering.

If you want to have a rapid solution, it is better to go to established treatments for which we know what to expect. Now in this case, in this case, in particular, yes, we went for something established like DBS, but this is the twist that at some point, we describe what’s in the book because we said okay, we will do DBS, but we also explored this new way of doing DBS, which is adaptive deep brain stimulation

Being Patient: Who would not be a candidate for deep brain stimulation?

Fasano: There are different reasons not to be a candidate for these treatments. First of all, this is a brain operation, and therefore, some people might be too frail to go for it. If they are too old or have [already] suffered for years, and maybe there are some vascular problems, like many strokes in the brain, that will be one reason.

Another reason will be people with particular problems like balance problems [and] cognitive problems, because we know that in these people, if we were to do a brain operation— chances are that we can make those particular problems worse. Maybe we can treat the tremor, we can treat all the classic signs of the disease, but those particular issues that are actually the reason why the person is looking into surgery in the first place might not improve or might get even worse. Another example will be speech.

“If you want to have a rapid solution, it is better to go

to established treatments for which we know what to expect.”

Then, there are many others, including the expectations and motivations of the patients. We want people [who] go through this process to be motivated to be again, as I mentioned earlier, active participants [in] their care. But at the same time, if they come with excessive expectations, being cured, we don’t think that they’re good candidates. [That’s] because they’re going to be depressed afterward, they’re going to be disappointed.

In fact, in the past, we had also cases of suicide 20 years ago. When we didn’t really know how to even portray this process to patients, some people really got disappointed, and that, together with the drastic medication reduction that can happen with DBS, lead to severe depression and suicide, unfortunately.

Being Patient: What does it feel like to have implants for deep brain stimulation in your skull? Are you cognizant of it at all times?

Stecher: No, I’m not, thankfully. I gotta say the team that they have in Toronto is a fabulous team. They really know how to do it in such a way that’s minimally invasive. I could obviously feel it like in the months after I had the surgery, even now, because I just actually had a battery replacement about two weeks ago, I can still feel the new battery plant that I have here in my chest.

If I press here, then I do feel obviously something like something alien in my chest, and there’s no going around that. I do feel the wiring through my neck as well. So, these bumps on my head, but they’re not that big of a deal for me.

Being Patient: What’s the difference between adaptive and continuous DBS? What is working better for you?

Stecher: There was a period of time where we were trying out whether continuous would be better for me or adaptive was better. Continuous just means that it’s firing at the same steady rate throughout the day. Adaptive means that it’s reading out the activity and that it’s actually trying to better stimulate according to my specific needs.

I would say that adaptive has been better for me so far. It could just be my own biases, and I’m very biased. I have to admit my bias as well. I’m very open about that because, as a participant. I’m still participating in these new adaptive PD trials as well. All that’s kind of clouding my judgment, to some degree anyway, but I do feel as if this adaptive signal is better for me.

Being Patient: A member of our audience is asking if beta is the correct feedback signal for adaptive DBS. Have you had significant improvements as your implant has been using beta as the feedback signal?

What beta means [is] that I think a certain frequency at which every neuron in your brain pulsates. It’s pulsing between 70 and 37 hertz—that could be wrong; please correct me if I am. It seems that reading, and then it’s modulating stimulation from the battery, according to that reading that it’s getting, it’s also trying to match it to my symptoms. But it’s not doing a perfect job with that right now.

“We want people [who] go through this process to

be motivated to be again, as I mentioned earlier,

active participants [in] their care.”

Although it seems to be getting better and better over time as well, I do feel better today than I felt right after the surgery. After we turned on this adapter for the first time, it was still far from perfect. I hope that it’ll continue to get better as we go forward in the future.

Because right now, it’s only modulating the amplitude of the wave. It’s also the frequency and the shape of the wave that I hope for in the future devices, or I might not be lucky enough to have them, but whatever, I do hope that future devices will actually [be] modulating. There are other parameters as well because I think that those are also part of this disease. They’re part of actually better-treating patients like myself.

Being Patient: You said that you feel a lot better than when you first got the implants. Is that just because you’ve had to work on getting the right frequency and stabilized according to your symptoms?

Stecher: For example, and this is something I give Alfonso and his team a lot of credit for, is that they’ve done a very good job learning for me what works for each patient that comes into their office. To further complicate this whole procedure, there are four contact points at the end of each electrode.

At the beginning, and this is what they thought soon after my surgery was done, they thought that I only need to light up the second bottom most electrode. However, we’ve learned over time that I actually respond better if we let it be the second and the third one together.

Alfonso can talk about that in more detail than I can, obviously, but so it’s been a continual learning process, what’s working for me as a patient. They’ve been kind enough, and they’ve had the time and the energy to actually help me better live my life, as well as the input that I’ve given them.

Being Patient: Who controls that? When you need to change a frequency, or you need more in one area, what does that look like?

Stecher: I tend to defer to Alfonso for that because I just go back to the clinic. Whenever [I need] any of those kinds of changes. The amplitude of the wave that’s changing by itself that’s the algorithm at work. Everything else was Alfonso’s magic, and that’s the real result as well.

Being Patient: Is the algorithm reading what you need at certain moments and adapting accordingly? When it comes back to the office, what do you do, Alfonso?

Fasano: The other missing part, practically speaking, is the programmer. In this case, the neurologist myself— we use a special tablet. We program the device to communicate with a wireless system. I have a tablet, simple like that, and with that tablet, I can control certain parameters.

Importantly, when it comes to amplitude, which is how much stimulation to give, I don’t need to set certain parameters; I set a range. That range goes up and down depending on how much beta there is in Ben’s brain.

“They’ve been kind enough, and they’ve had the

time and the energy to actually help me better live

my life, as well as the input that I’ve given them.”

Beta is just one of the biomarkers. Going back to [the audience] question, we’re now learning all the other biomarkers. We know that other frequencies are encoding tremors, others [are] for involuntary movements, others [are] just for voluntary movements.

The good thing about all we’re doing right now is that we’re also planning to learn more about how the brain works in general, regardless of the disease.

Stecher: Now the hope is that soon we will have other diseases as well. There are clinical trials for all sorts of other indications.

Being Patient: Is deep brain stimulation being applied to different types of dementia, like Alzheimer’s disease?

Fasano: For Alzheimer’s, there have been studies, a quite promising small initial study followed by a double-blind, randomized control trial that, unfortunately, was negative. Again, it’s important to explain what these trials were because they were portrayed as DBS for Alzheimer’s disease, but in my opinion, this was more DBS for memory because the electrode was placed in the structure of the brain called the fornix, which is used to enhance learning. So, the circuit in function, [when] we want to learn new things, we want to remember something that we’re told, for example.

“The good thing about all we’re doing right now

is that we’re also planning to learn more about how

the brain works in general, regardless of the disease.”

DBS can probably help memory consolidation, but it doesn’t offer solutions long term, it doesn’t address the degeneration. The interesting thing about the second trial that I was talking about, the bigger one that was negative, is that when researchers started to look into the data, they realized that a group of people did better than others.

They saw that the difference was mainly related to age. To their surprise, they found that people with an age at onset, I think just surgery above 65, did better than the young onset dementias. The third trial is now ongoing with some problems, and this third trial, as you can imagine, is only enrolling people above the age of 65. But again, it will be a treatment for memory, not for Alzheimer’s in general.

Being Patient: Is there an option for people who don’t want to have the invasive DBS to have a non-invasive DBS? What do we know about its efficacy?

Fasano: Probably the one treatment that everybody’s thinking about right now is MRI-guided focused ultrasound. To step back, we know that certain parts of the brain [are] working too much. In Parkinson’s, there are these two nuclei that are doing too much of a bad job: the subthalamus, which is the target where the electrodes are implanted in the case of Ben, but another one will be the globus pallidus.

Now, either we control the activity of these neurons with electricity, or we kill these neurons. We will expect to see the same results with the difference that, as you can imagine, killing neurons is irreversible. If you have problems, you cannot get rid of them.

So, a focused ultrasound is a way to kill these neurons without opening the skull. It consists of shooting over 1000 acoustic waves from different angles, and they all converge in the spot of the brain that we want to lesion, that we want to get rid of. This has been done for Parkinson’s, using three different targets: the thalamus, which helps the tremor; the globus pallidus, which helps dyskinesias and, to some extent, the other problems of the disease; and even the subthalamus, where Ben has electrodes, has been lesioned using ultrasound.

However, like I said already, this is an irreversible procedure, and people think that simply because there is no opening and they just lie down in their special MRI machine, that this is not a surgical intervention. Instead, it is a brain operation like any other, it is appealing because there is no opening of the skull and the skin, but it still carries risks.

Being Patient: You’re penetrating the brain blood barrier, right, with a focus ultrasound?

Fasano: No, that’s something else. The same technology-focused ultrasound can be combined, changing the type of the power and so it’s a lower intensity focused ultrasound, combined with IV injection of microbubbles. These bubbles oscillate while they’re under the effect of the ultrasound so we can basically make them get bigger when they are in certain parts of the brain.

They’re circulating in the bloodstream. When they are exposed to ultrasound, they get bigger and they vibrate basically. This creates an opening of the so-called broad brain barrier, which is a barrier that protects the brain, which is good to have, but it also comes with downsides.

For example, if you want to deliver specific treatments to the brain, chemotherapy, in case of cancer, or gene therapy, in case of experimental treatment, these molecules or viruses cannot get into the brain. So, now the idea is to combine opening the blood brain barrier with oxytocin and micro bubbles, so whatever intervention you’re offering, the patient can penetrate the brain and not just enlarge the brain in that particular spot. So, that’s actually very interesting.

Being Patient: Is there a path from Parkinson’s treatment to cure, and what do we need to get there?

Stecher: At the moment, I would say that the path from treatment to cure is a blurry one, but there’s a lot of hope that your life will improve after you get a proper diagnosis and if you get seen by a proper specialist like Dr. Fasano. However, that’s a key part, and it’s a very difficult thing for a lot of patients to actually get to actually be under the care of somebody like Alfonso there because most patients don’t have access to that kind of specialists, and those kinds of care centers.

However, the ultimate goal is still to cure these diseases. I don’t see anything coming online soon that will actually stop this degenerative process, but I do see that these DBS systems are getting better and better over time. I hope that, over time, it will continue to improve.

It’ll continue to address more symptoms, and then it’ll be using more nuclei. I mean, in my opinion, these diseases are the symptoms. I can’t feel the degeneration happening in my brain, I can feel the tremor, but I can’t feel the concept of nucleon forming, so I think we could, if we could actually address symptoms, I think we would be a long way further and actually help more people.

Being Patient: Before you had this treatment, you were seven years or so post-diagnosis. How did it feel before getting the implant, and how did you feel after starting DBS therapy? What has changed for you?

Stecher: Prior to getting DBS, I was declining pretty rapidly at the time. It was at the height of the COVID pandemic, so the world felt like it was kind of declining all around me. All that stress, all that accumulated, made me feel a lot worse than otherwise would.

I was very dystonic, which means I had that posturing of my hands like that. I had a very pronounced tremor like I was saying, and I had bradykinesia as well. My movements [were] very slow, especially when I didn’t have any medication. As soon as Alfonso turned on this DBS for me for the first time, I felt like the whole world had been lifted off my shoulders.

It was a complete relief, and it was very sudden, too. Even faster than I was expecting it, but it was that immediate relief. [It was] very stark and very surprising even to me. I mean, it was kind of like the best expectations that I was hoping for. But until he actually turned it on, I didn’t know that I was going to experience the full benefits of this procedure. Then once he did, I knew that I made the right choice, and I was in good hands.

Being Patient: We have a question from our audience. When are the results from the adaptive DBS clinical trials going to be released? She says that she’s heard that adaptive DBS really didn’t show better symptom control, but it did conserve battery power and battery life.

Fasano: The results have been released in poster format during the major conference that we have, an international conference called the Movement Disorder Society Conference. It was last year in Denmark. The results have shown that adaptive stimulation works and it’s safe.

Now, adaptive PD, which is the trial that we’re talking about in the trial that Ben alluded to, was meant to show that adaptive stimulation is safe, and it’s better than nothing. So, in that sense, it’s a positive trial, and it’s probably the trial leading to approval. Actually, I should also say that, in Japan, this treatment has already been approved so probably little by little all countries will have the approval.

“As soon as Alfonso turned on this DBS for

me for the first time, I felt like the whole

world had been lifted off my shoulders.”

The key question, which we don’t really have an answer yet, is whether adaptive stimulation is superior to continuous classic stimulation, and if so, for what type of problem and for what type of patient. That’s why there are other trials coming up in Toronto. We have a trial that has just started called Canada trial which stands for continuous versus adaptive deep brain stimulation, blah blah blah.

The goal is exactly to look at whether gait, speech, by allowance, is better when people have adapted stimulation versus continuous in a double blind fashion. We’re focusing on gait, balance, and speech because, first of all, these are not well treated with current treatments, including continuous DBS, and second, because they are major determinants of quality of life for people. So, we’ll see.

Being Patient: How hard was this treatment for Parkinson’s to find? For the people who are watching this, can they go to their doctors and ask about trying adaptive DBS?

Stecher: It depends entirely on where they happen to live and where their neurological office is. If they’re in one of the bigger centers, like New York, San Francisco, or Toronto, then I would say that they probably do have access to this kind of therapy, but they happen to live somewhere where they do not have access to the best therapists in the world, the argument that maybe continuous might be even better for them.

Adaptive does require expertise, and does require more fine tuning from what I’ve seen anyway. That’d be my basic recommendation, if they happen to live in a big city center with access to some of the best neurological minds in the world, then they can probably get this adaptive version. If not, then I think continuous is also available for most patients as well.

Being Patient: Is it expensive? It sounds like you have to go to the neurologist a lot to get things tweaked.

Stecher: It can be pretty pricey if you’re paying for everything out of pocket. I think a lot of insurance companies, so if you’re living in America, [they do] cover it. It’s an advantage of being here in Canada,

Fasano: I can add something to this. Ben, obviously as a patient advocate, is concerned that a lot of people will not have access to treatments. I will say generally speaking in Western countries, there’s a good understanding of DBS and you don’t necessarily need to go for adaptive DBS.

“It’s good to start a relationship and a collaboration

with your neurologist and ask questions.”

I think the message is that people go to their neurologist and ask, “Okay, what’s on the table for me? I heard about DBS. Is it good for me or not? If not, why?” It’s good to start a relationship and a collaboration with your neurologist and ask questions. That’s all you need to do. Most likely, the neurologist will know what to say, and if not, change neurologists, of course.

Stecher: If you’re not sure about which questions to even ask, you can buy our new book Reprogramming the Brain. We have a checklist of all the different questions that patients should be asking them.

Being Patient: How far away do you think we are from using this neuromodulation technology to treat other dementias? Is it way down the pipeline, or are we getting closer?

Fasano: I don’t think we’re close. I may be wrong, but like I said, these are complex diseases. In a way, Parkinson’s is an easier problem because, as you heard from Ben earlier, the neurodegeneration starts from a single spot in the brain. We know what parts of the brain are not really working.

In dementia, there are more areas of the brain affected and dementia affects functions that are very complex and are difficult to replace. I may be wrong also because technology is interesting because it’s an exponential growth because from one discovery, you’ll get to two, three, four and so forth.

For example, the trial was telling you earlier about fornix DBS wasn’t intended to be for memory problems or dementia; it was serendipity. It was DBS done to treat obesity. During surgery, the patient was awake during surgery. The surgeon here in Toronto, Dr. Rosano, turned the stimulation on, and the patient started remembering things from the past. Then they noticed that the higher the stimulation, the more clear this memory was forming in this person’s brain. So, from that serendipitous discovery, they decided to do a little trial, and then things evolved.

You never know. It’s important to keep our curious mindset, and at the same time, be careful and not so excited about anything you might hear on the internet; to fund research, fundraising is very important, because a lot more can be done.

“It’s important to keep our curious mindset, and at the same time,

be careful and not so excited about anything you might hear on the internet.”

Being Patient: Ben, is there anything else that you want to add or say before we go?

Stecher: [To] patients out there, my message basically is pretty simple. Don’t let other people define this disease for you. You should try and go out and do the best you possibly can with the tools that you have to define it for yourself.

I think that’s one of these lessons I’ve learned along the way as well. Do what you can to surround yourself with good people as well. Having a great team around you and having people who care about you, that will make the difference between having good outcomes versus bad outcomes in many cases.

Katy Koop is a writer and theater artist based in Raleigh, NC.