Longeveron published new results from a small Phase 2 trial testing its stem cell therapy in people living with Alzheimer’s disease.

Since their discovery in the 1960s, stem cells have captivated our curiosity. Unlike other cells in the body, stem cells are changeable — they can self-renew and they can differentiate into different, specialized cell types, raising the possibility that we could one day regenerate damaged tissue and organs. But when it comes to Alzheimer’s and dementia, stem cells haven’t lived up to the hype.

Still, many research groups and companies continue to rigorously test these treatments, probing their potential to restore brain function. Drugmaker Longeveron recently published a phase 2 study of 49 patients in Nature Medicine testing their stem cell treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.

Intriguingly, the treatment is also offered at cost, as part of a trial registry — where prospective patients who meet certain criteria are eligible to receive the drug — in a clinic in the Bahamas. Patients are then followed over time to see whether they improve.

Can laromestrocel treat Alzheimer’s?

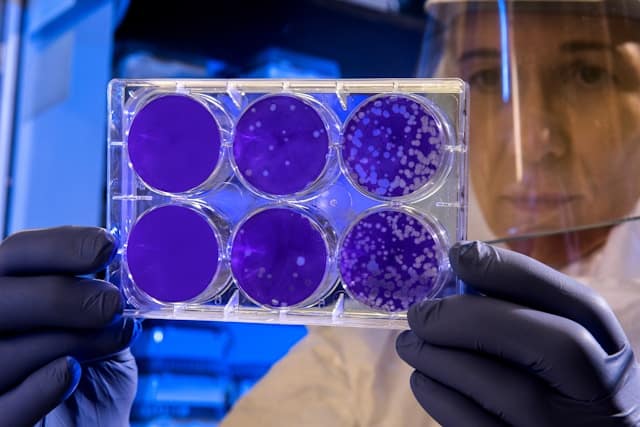

Longeveron’s therapy, laromestrocel (Lomecel-B), is made of mesenchymal cells taken from the bone marrow of healthy adults. Mesenchymal cells can transform into cartilage, fat, or muscle cells and secrete proteins that may regulate the immune system and the blood-brain barrier.

In the study, researchers randomized their 49 trial participants across four different groups. Each participant received four monthly infusions.

- One group received four placebo infusions.

- A second group received one infusion of 25 million cells, followed by three placebo infusions.

- A third group received four infusions of 25 million cells.

- A fourth group received four infusions of 100 million cells.

The main goal of the trial was to test whether the treatment was safe. Across all groups, serious side effects occurred in fewer than 10 percent of participants.

“The drug appears to be quite safe,” Longeveron vice president Brian Rash told Being Patient. Although the study was small and more research is needed to confirm, he said that the drug showed “potential signs of efficacy” in treating cognitive symptoms and improving daily function.

However, neurologists looking at past research — including the fundamental question of whether these cells are in fact “stem cells” — aren’t feeling optimistic.

Though there is pushback on this trial, two small trials testing stem cell-derived brain cells intended to replace dead and dying cells in Parkinson’s disease show promise and are headed to Phase 3 trials later this year.

Pushback on laromestrocel

But the results on cognitive and functional measures — the study’s secondary goals — were less straightforward. There was a lack of consistency across the cognitive assessment and more doses of the treatment didn’t always lead to better outcomes.

Lastly, the researchers also found that treatment with laromestrocel may have slowed brain shrinkage in the test group. This was an exploratory outcome in the trial, meaning that the trial wasn’t primarily designed to measure this. While the data may be interesting, it isn’t definitive, and more research is needed to confirm these effects.

Research studies conducted by other stem cell scientists have cast doubt on the idea that these types of stem cells survive in the body long enough to have a physiological impact.

Dr. Arnold Kriegstein, a UCSF neurologist and leading expert on stem cells in neurodegenerative disease, who isn’t involved with Longeveron, isn’t convinced, expressing skepticism about the findings — and the rationale behind the treatment overall.

Kriegstein called the results “paradoxical.” At times, the lowest dose seemed to have the best impact. The treatment didn’t follow a standard dose-response. For most medical treatments, there is a dose where we expect to see a minimal effect and a dose where there is a maximal effect.

Further, Kriegstein added there isn’t any evidence of this dose-response in the trial data — casting further doubt on the treatment’s effectiveness.

Many of these cognitive tests are also affected by day-to-day fluctuations. A person’s score might be a few points higher one day because they didn’t sleep very well, for example. Kriegstein said that these tests become more reliable in larger clinical trials. For a treatment like this to work, Kriegstein said, stem cells would need to either persist in the body or exert a lasting biological effect.

“I don’t find there’s evidence for either of those things,” he said, referring to previous studies.

A 2012 study injected mesenchymal stem cells into mice to see what would happen in the body. After an hour, most of the stem cells were found in the lungs, but they did not live longer than 24 hours and did not reach any other organs. Instead, pieces of dead cells were later found in the liver.

“The cells are very unlikely to survive longer than a few days,” Kriegstein speculated. “They get filtered by the liver.” Some cells, he said, may survive for a bit and travel to the lungs, but

Research hasn’t definitively shown that the proteins and signaling molecules secreted by these cells actually affect the brain in human trials.

Beyond these potential disadvantages of the study methodology, there’s a more fundamental question: Is this a stem cell therapy?

Stem cells are cells that can turn into multiple other types of cells. Longeveron has framed mesenchymal cells as stem cells — but are they? The scientist who discovered mesenchymal stem cells, Arnold Caplan, disavowed this terminology in 2017, suggesting that calling them stem cells could mislead consumers. (To Longeveron’s credit, the company does not claim that the cells turn into new neurons.)

“Unfortunately, the fact that MSCs [mesenchymal stem cells] are called “stem cells” is being used to infer that patients will receive direct medical benefit, because they imagine that these cells will differentiate into regenerating tissue-producing cells,” he wrote. “Such a stem cell treatment will presumably cure the patient of their medically relevant difficulties ranging from osteoarthritic (bone-on-bone) knees to various neurological maladies including dementia.”

He does think that it is worth studying whether these cells exert beneficial effects in clinical trials.)

Then, in 2018, stem cell scientists Douglas Sipp, Pamela G. Robey, and Leigh Turner, published criticism in Nature of companies that sell mesenchymal stem cell treatments for “selectively highlighting” studies “indicating that the cells secrete all sorts of healing factors” while ignoring the evidence that they play more “limited roles.”

Rash acknowledged that more data is needed to understand how the treatment might work.

What’s next for Longeveron?

Though the company completed this trial in 2023, Longeveron has not yet registered a phase 3 trial that would definitively test whether the treatment is effective. This trial would be required to win regulatory approval. Rash said that the company is actively planning the trial.

The company is also testing the same treatment for age-related frailty and a rare congenital heart condition called hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Kriegstein thinks it’s problematic that the company is claiming the treatment could be effective for a range of diseases that have different biological mechanisms.

The stem cell treatment is already available to patients at an independent clinic in the Bahamas. People who receive the treatment need to pay out of pocket, and the cost is determined on a case-by-case basis, though Longeveron indicated the price would likely be in the thousands.

Participants who receive the treatment take part in a trial registry, meaning some of the data could be used to help researchers understand if the treatment works. The trial registry is regulated by the Bahamas National Stem Cells Ethics Committee.

“It is unethical to charge patients who enroll in a trial for an unproven therapy,” said Kriegstein. “It also creates bias that can influence the outcome.”