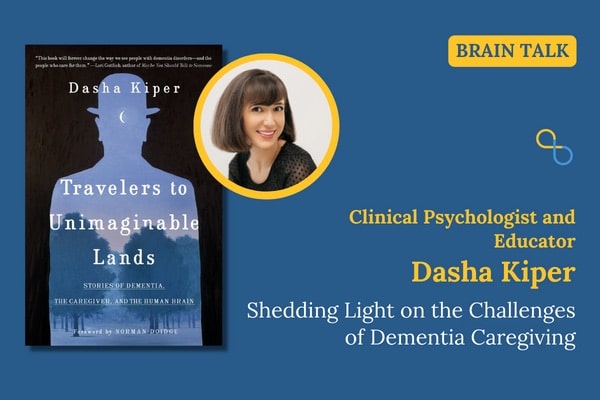

Clinical psychologist, educator, and author Dasha Kiper joins Being Patient Live Talks to discuss her book "Travelers to Unimaginable Lands," which uses storytelling and research to explore the impact of dementia caregiving on the brain.

Dementia doesn’t just affect the brain of a patient. As clinical psychologist, educator, and author Dasha Kiper explores in her new book, the disease can leave indirect marks on the brain of a family caregiver, too.

Some 94 percent of dementia caregivers sleep-deprived, and many experience burnout. Caregiving for a loved one with dementia can take a heavy toll on one’s health and wellbeing — and it can sometimes lead a person to react in ways they didn’t expect — no matter how much they know about the disease their loved one is experiencing. Kiper explores these radiating, second-hand effects on caregivers in Travelers to Unimaginable Lands: Stories of Dementia, the Caregiver, and the Human Brain.

“What I noticed is that no matter how much I read about this disease, that no matter how much I understood the symptoms intellectually and understood what was happening to his brain,” Kiper retold her experience assisting a son caregiving for his father, “I found that when he would get extremely angry with me… I still felt it as so painful, in part because I was really trying to do my best.”

Her book’s title is a reference to a case study in “The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat” by neurologist Oliver Sacks. And as a New York Times review that highlights Kiper’s and Sandeep Jahar’s recent books pointed out, the work is “particularly rich with literary references.”

Taking her clinical experience, as well as stories of caregivers and people living with dementia, she also uses cognitive and neurological research in the book to shed light on the pressures on caregivers. Drawing from her own experience and in counseling, Kiper illustrates how Alzheimer’s can affect not only the person with the disease but the caregiver.

Previously the Clinical Director for Support Groups at a New York Alzheimer’s Organization, she has led groups for people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s and caregivers of those with dementia disorders. Kiper has also trained and supervised mental health professionals who work with dementia caregivers.

In conversation with Being Patient’s Mark Niu, Kiper discusses what it means for caregivers to traverse the “unimaginable” territory of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Read or watch below to learn more about this book on dementia, caregiving, and the brain.

Being Patient: You have experience being a caregiver yourself and working with caregivers of dementia, navigating the “unimaginable” territory, as you call it. Can you tell us about that experience?

Dasha Kiper: I was studying pathology and clinical psychology, but I was mostly doing research. I was so craving a kind of a person interaction, which I wasn’t getting any of. I mentioned this to a friend, and he said, “Oh, I have this man who has memory loss, and his son was desperately looking for someone.” I thought, “Okay, this might be good for a couple of months.”

I went in there, and I was so intent on really trying to understand everything that was happening to his brain, what his struggle was, and really eager to try to be as helpful to him as I could.

Being Patient: These experiences can be somewhat traumatic, even to see and experience. Why did you feel the need to write this book?

Kiper: When I was taking care of this gentleman in the Bronx, I compulsively began to read all the literature there was: how do you communicate with somebody who has dementia, understanding what’s happening to their brain? As I pored through all the literature, what I noticed [was] that my brain was also becoming more and more affected, and I didn’t see that reflected in the literature.

I began to feel really kind of ashamed, as was what was happening to me. Because despite reading everything I could get my hands on, what I noticed is that no matter how much I read about this disease, no matter how much I understood the symptoms intellectually and understood what was happening to his brain—I found that when he would get extremely angry with me when he would become accusatory, which is very typical with dementia, and I understood that, I still felt it as so painful, in part because I was really trying to do my best. Then I felt insane for taking those symptoms personally because I understood very well that there was nothing personal to it.

“What I couldn’t find is a reflection on the caregiver’s experience: what’s happening to their mind.”

I understood that [it] was Alzheimer’s at work. I began to see that his son, in his own way, was also behaving in ways that betrayed what I taught him about the disease, as well. I thought I really wanted to find more information about what was happening to the caregiver’s brain because we’re social animals. What I couldn’t find is a reflection on the caregiver’s experience: what’s happening to their mind.

I read a lot about that; there’s a lot of heartbreak. I read about the sadness, the financial costs, [and] the psychological costs, but not what I was experiencing and what I would soon see when I would work with caregivers. I didn’t see that reflected.

Being Patient: How did you approach finding the research on cognition and neurology for the book?

Kiper: Well, at first, I began with a question. This partly came also with my clinical [experiences] dealing with caregivers because after having my own personal experience and seeing the son kind of respond in ways that were irrational, I began to be really drawn to the caregiver’s dilemma.

I think it began with a general clinical question that I kept observing that no matter how well-intentioned, sophisticated, oftentimes kind, resourceful, [or] reasonable the caregiver was, what I found is that they kept on confessing to me that they still kept arguing with their wife or their mother, that they kept on struggling to enter their reality. They said to me, “I read a lot about how I’m supposed to behave, and sometimes I manage to do it, but other times, I don’t.”

A lot of the humor that came from my support groups where people [were] confessing how crazy they were behaving at home, and I began to find it interesting. So, I thought to myself, “What is dementia doing to our brains that oftentimes we become more irrational than the person that we’re taking care of?” So, the question was: what are the needs of the ordinary healthy brain, and how is Alzheimer’s undermining those needs? How is Alzheimer’s disease making it very difficult to adapt to this new reality?

Being Patient: The book has so many different stories and scenarios that you bring up, and all of them are a little bit different in the psychology of what each caregiver is going through. How did you choose these particular stories?

Kiper: I spoke to so many caregivers. I wanted to make sure that the stories were varied enough that they would give access to different questions. Because every chapter is broken down into different themes that I’ve seen caregivers struggle with: why do we take symptoms so personally? Why do we argue? Why is it so hard to remember that it’s their brain that’s acting up? Why is it so hard to stop blaming them, even though we know that the disease is culpable?

I tried to find those stories that reflected those big questions that I saw that were universal when I spoke to caregivers. On a personal level, I really adored the people I spoke to. So, I wanted to make sure that when I’m catching people [behaving] at their most vulnerable and irrational, that these people were also very loving and kind and just struggling human beings.

I hope what came across in the pages is that I truly enjoy talking to them, and I really admire them as well. That was very important to me— that it doesn’t look like I am exposing these people but that the stories reflect a universal experience.

“I tried to find those stories that reflected those big questions that I saw that were universal when I spoke to caregivers.”

Being Patient: I can tell you that some of the cases that you brought up were surprising to me. The example of a couple having an evening out. Every time they go home, or quite often when they go home, he completely forgets. She has to keep trying to prove that she is his wife and keeps trying to bring up, “Look, my clothes are there,” and he says something to the extent that she planted her clothes. Those stories might be even more common than we know, but was there anything that surprised you when you did your research? Were there any stories that caught you by surprise?

Kiper: I think that the more I began to research about the brain, and I went a lot into social neuroscience, cognitive psychology, philosophy of mind, and the more I really began to understand the needs and biases and proclivities of the healthy mind. I assumed that this disease was agonizing. I didn’t realize how cognitively draining this disease is and how stubborn our minds are about certain things that dementia requires that we give up.

For example, our minds have a very hard time giving up a mutual reality. Our minds really struggle to give up the idea that somebody else is responsible for their behavior. There are evolutionarily good reasons why our brain does that. It really floored me how wonderfully, on the one hand, our brain is resilient; it’s adaptive, but it is compulsively social.

When you’re compulsively social, [your] brain has very rigid rules about how it expects other brains to behave. That’s when I began to go, “Aha,” that’s the reason it’s so hard to accept this disease, even when intellectually, you know all about it. Our brain is just so committed to connections with other human beings.

I really began to understand why it’s so hard for caregivers to accept it. It’s not because caregivers are mean or stubborn or rigid; it’s because our brain has needs too, and I think it’s very easy to forget that because we’re so consumed about the needs of the the sick brain, of the struggling brain of the brain that has the disorder, we assume that we can do anything. I found that that’s just not the case.

Being Patient: It’s something I struggle with. My mom is at an earlier stage of Alzheimer’s, and I think this issue is also brought up in your book. Do I need to try to prove to my mother that you, indeed, are forgetting things and you are sick? Or is it better to just help her out? Should I make it clear to them that they are not well, or is it better not to disturb them and upset them? I mean, it may depend on what stage of Alzheimer’s someone is at, right?

Kiper: I mean, this is such a fraught, ethical question, too. Because at what point do you start lying to your mom, and that’s already a threshold. It’s a very, very difficult thing. It puts caregivers in this moral dilemma. When do I start lying to my mom? When do I start going against her needs?

Let’s say she says, “I don’t want anybody in the house.” When do you feel like her concerns for safety override what she wants? So, I think people don’t realize that on top of all the stress that you’re dealing with your mom, you’re also forced into these ethical conundrums. It is always my bias, although I will say that this is just my view; there are different people in the field who have different perspectives. I think that at a certain point, for the sake of both the caregiver and the person dealing with dementia, our objective should be shielding their self-image.

“What I’ve noticed is that no matter how much cognition declines, a person’s self-image actually persists.”

What I’ve noticed is that no matter how much cognition declines, a person’s self-image actually persists. I think that we should be very keen on preserving it. If we find that the person is just not accepting this disease, I think that for everybody’s well-being, the ideal thing is not to confront them with this disease because I feel that they cannot handle it. It puts too much of a burden on both parties.

I say that to you, but that’s a very difficult thing to actually execute. Because your instincts are like, “No, Mom, we went through this. You have a problem. I’m here to help, right?” Because you want her to accept your help. You want her to kind of want her to understand where you’re coming from, and all that requires is her understanding that she has a problem.

Being Patient: I have one of those passages that relates to exactly that from your book. You say on page 157, So, when do we need to accept that a parent, spouse, or friend is no longer morally accountable, that someone is no longer a person to be trusted to choose? To choose the right thing, it’s an ethical dilemma bound to haunt caregivers and explains why, in many cases, caregivers wait too long before taking away driving privileges or attaching a tracking device, or bringing an aide into the house. Safety matters, of course, but so does a person’s integrity, which is tied to a feeling of autonomy. But in dealing with the disease, there is rarely a clear divide between right and wrong. There are only trade-offs. That’s exactly what we’re talking about, right?

Kiper: This is the reason I so loathe to tell caregivers what to do, even though they oftentimes desperately want the answer. I think it’s the ambiguity in this disease that’s so hard because I could tell you that who am I to say when it’s right for you emotionally to start lying to your mom?

The tricky thing is, oftentimes, your parents— they taught you right from wrong they gave you these moral tenets to live by. Sometimes, dealing with them effectively with dementia means betraying the very things they taught you when it comes to human decency.

Still, even with parents also, they might be enfeebled in many ways, but they could still be very intimidating. They could still loom large, no matter how old you get. So, to go against their wishes is really daunting. I think people don’t realize how intimidating somebody can still be, no matter what stage they are in their dementia decline.

Being Patient: What are the things you would like caregivers to know?

Boy, so many things. There’s been so much attention paid to the brain of what the person living with dementia is going through. What I really hope that they get through in reading this book is the more they understand the human brain and how we’ve evolved to interact with other human beings, that when they begin to see their own behavior, that maybe when they’re arguing or when they’re behaving in ways that they probably shouldn’t, that they could give themselves a little bit of compassion.

They could give themselves a little bit of forgiveness, to say, “Oh, I’m reacting in a very human manner,” that most people are struggling to do this, that dealing with this disease is not just sad. It’s not just financially costly; it’s cognitively draining, and it’s morally, oftentimes impossible— that there are no right ways to behave.

“As I said, there are trade-offs, and it’s never going to feel good. You’re never going to feel like you’re doing the right thing.”

As I said, there are trade-offs, and it’s never going to feel good. You’re never going to feel like you’re doing the right thing. You’re always going to be haunted by guilt. Because this disease is going to make you feel that no matter what you choose to do, it’s never quite right or good enough. And that’s because of the disease. It’s not because of anything that you’re doing. That’s wrong.

Being Patient: We got a comment from the audience. In Traveler’s to Unimaginable Lands, you shed light on how the problems in relationship dynamics after Alzheimer’s are magnified afterward. This viewer finds that lifelong personality struggles were magnified between her sister and herself after they tried to share care of their father after he got dementia.

Kiper: Oh, I hear you. This is such a major issue in support groups, too. I mean, on top of all the hardships, there’s also the strain on family dynamics. What I find is that oftentimes, the person who has dementia not only are their personalities and challenging behavior amplified, but also the family roles also become amplified.

The person who is most likely to be the caregiver becomes even more consumed by this task. People have different positions on what should happen. I think that it’s very, very hard to navigate. It’s very hard to navigate these family dynamics, especially when you’re making these difficult decisions with others in mind. The tricky thing is both parties could be completely right, and they can both disagree strongly with one another.

Being Patient: What do you hope readers actually learn about dementia and the brain?

Kiper: I would like them to learn that people who have dementia, I think that maybe in the media, people who have dementia are oftentimes portrayed as very passive [and] in the very, very late stages as completely helpless— what I want them to understand is that the reason you’re being tortured by your family is because they’re not that helpless.

The brain is very complex. Yes, there’s a disease that’s making it very hard for them to do various things like follow instructions, and maybe they can’t remember, but they’re still [there]. They could still be emotionally and cognitively shockingly nuanced in certain ways.

I think they’re still capable of driving you crazy because they do have so many of their old abilities. So many unconscious processes are not necessarily erased because of this disease. When people tell you, “Oh, that’s just the disease. It’s not your mom,” I would like you to take them with a grain of salt because you know that there are many parts of your mom that are still there.

They still could be as loving and could be as exhausting and irritating and infuriating— as you’ve always known your mom to be. People who have dementia are a lot more complex and a lot more capable than people give them credit for. The healthy brain can be as helpless, as irrational, and as volatile as the person who has the disease.

“People who have dementia are a lot more complex and a lot more capable than people give them credit for. The healthy brain can be as helpless, as irrational, and as volatile as the person who has the disease.”

So, this divide [is] that we oftentimes think you’re healthy, so that means you’re perfectly capable, you’re unhealthy, that means you’re completely helpless. I don’t believe that is an accurate depiction of what happens, and I believe that’s an invalidating description of a caregiver’s experience.

Being Patient: I’m a writer too, and sometimes we’re taught to go toward the pain, but sometimes you really don’t want to go there. I want to know about your writing process for this book and how you managed to navigate and deal with such a heavy subject.

Kiper: Oh gosh, my writing process is pretty torturous. In part because I think that as I was writing this book, I was also listening to caregivers. Because I was surrounded by their pain, I don’t think it was their pain that made it difficult. It was the responsibility of reflecting that pain accurately that, I think, really weighed on me.

I felt such admiration and awe when caregivers were able to express to me the reality of their experience. So, I felt a tremendous responsibility to accurately portray that. That was the real kind of writing difficulty, and of course, to kind of do a mixture of stories and science so one would not overtake the other.

Being Patient: What’s next for you? Are there any readings for the book or events coming up?

Kiper: Yes, I am going to be doing various talks I have at universities; I will be traveling to different places to talk. I’m actually working in a new place called Renewal Memory Partners, and I am the clinical trainer. What that means is I speak to mental health professional caregivers about some of the themes of my book and to try to educate them a little bit about the struggles and the difficulties that our brain has when it comes to adapting to and accommodating this disease— in hopes that people feel less alone and have a greater neurological framework of why they’re struggling.

Being Patient: Do you have future books in the works?

Kiper: That question put so much terror into my heart. I think that I need to pause and listen and learn more about my experience because it’s really the clients that really informed this book. So, I want the experience to lead the writing.

Katy Koop is a writer and theater artist based in Raleigh, NC.

I am in early days of dealing with dementia. So much is true for me, even now.

Hi Mary — Thanks for reading, and don’t forget that you are not alone on this journey! Keep in touch.

After a year I continue to read this article and i’ll buy her book. I’m from Italy and also with my poor english I would thank Mrs. Kiper for her work…

Thank you for being here, Alberto! You might enjoy this Live Talk with Dr. Sandeep Jauhar https://www.beingpatient.com/my-fathers-brain-sandeep-jauhar-alzheimers-caregiving/ – take care.