In Part 2 of a two-part series about gene therapy, we explore how pharmaceutical companies are zeroing in on gene therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. An expert digs in to explain what it is, how it works, and how Alzheimer's gene Apoe4 plays a key role.

This article was made possible through sponsorship by Lexeo Therapeutics. Being Patient’s editorial team produced the interview and article with no review/approval process by the sponsor. Explore the rest of our gene therapy series.

The root cause of Alzheimer’s disease is still unknown, but our genes appear to play some part in our Alzheimer’s risk. In early-onset Alzheimer’s, a version of the disease that affects people younger than age 65, they might play a lead role. Many Alzheimer’s treatments like Leqembi or cholinesterase inhibitors target proteins — the molecular machines of the cells. But what if doctors could go one level deeper and treat Alzheimer’s more effectively with a few quick changes to our genetic code?

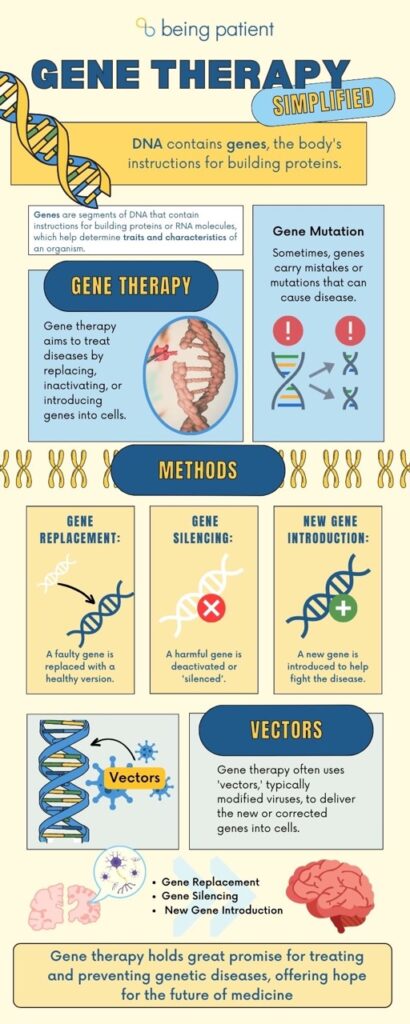

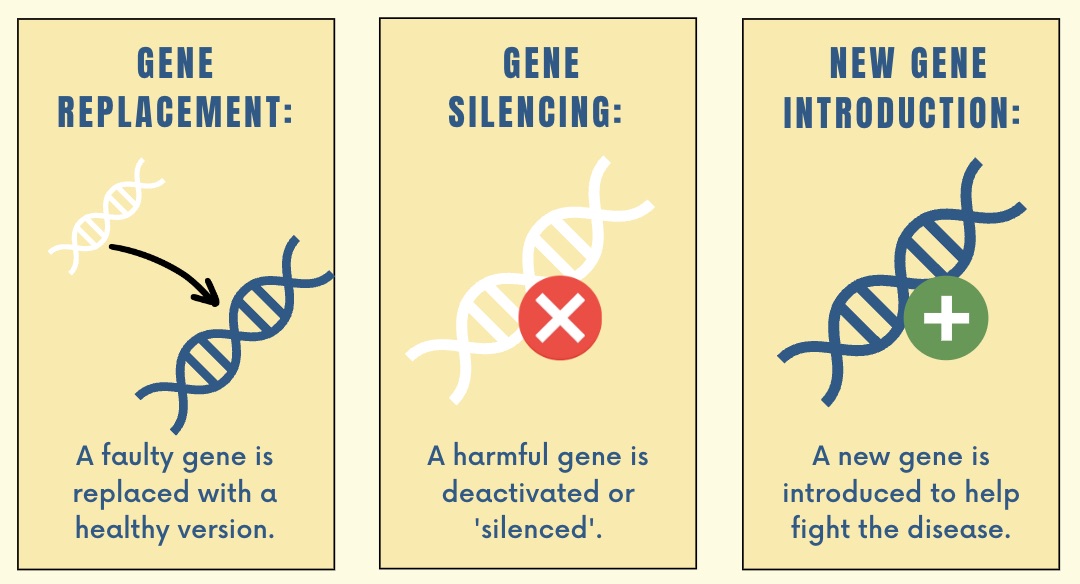

Gene therapy is a broad term used to describe medical treatments that, instead of medicines, use our genes themselves to treat diseases, from melanoma to spinal muscular atrophy. In the example of melanoma, gene therapy involves adding in extra genes into the body’s immune cells so that they can fight off cancer. In spinal muscular atrophy, the gene therapy delivers a healthy version of a protein that isn’t working in the brain. There are many more gene therapy treatments in the pipeline that would work by rewriting parts of the DNA: they all either replace harmful genes or gene variants, turn off — or “silence” — them, or introduce wholly new genetic material that has a positive effect.

To leverage gene therapy in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease, scientists are targeting the genes that have the greatest impact on Alzheimer’s risk.

Could gene therapy one day treat Alzheimer’s disease?

In the case of Alzheimer’s, editing the right genes could mean shutting down the disease before it even starts. One renowned researcher who’s been with the field of gene therapy from its start has set his sights on Alzheimer’s disease.

Cornell scientist Ronald Crystal, who developed some of the first forms of gene therapy — viruses loading genes into cells and organs — turned his attention to treating Alzheimer’s in 2004.

“Gene therapy is essentially a drug delivery system,” Crystal told Being Patient. “We’re all made up of about 25,000 genes, and we’re using those genes, essentially, as drugs. So, gene therapy is a strategy to try to prevent or treat disease by using genes as the drug.”

“We’re all made up of about 25,000 genes,

and we’re using those genes, essentially,

as drugs. So, gene therapy is a strategy to

try to prevent or treat disease

by using genes as the drug.”

In Alzheimer’s, he said, the target for this genetic drug is the brain cells.

“We’re not really altering the genes,” he explained. “What we’re doing is putting in a new gene — augmenting the genes.” In Alzheimer’s, he said, the gene he’s focused on is ApoE2.

Many scientists right now are trying to develop the first gene therapy for Alzheimer’s. Biogen, the drug makers behind Aduhelm and Leqembi, are also in the race, with their drug BIIB080 that stops the tau gene from making proteins. Researchers at Ohio State are in the earliest stages of testing a gene therapy that boosts the levels of a neuroprotective to slow the course of the disease. Other scientists that are working on mouse models of Alzheimer’s are hoping to develop human trials based on their results.

How do individual genes affect the risk of Alzheimer’s?

The gene that notoriously raises Alzheimer’s risk

In over 95 percent of Alzheimer’s cases, the exact cause of the disease is unknown. However one risk factor gene, which encodes a protein called apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is the biggest risk factor. Each person carries two total copies of the ApoE gene, inheriting one variant from each parent.

There are three different variants — ApoE4, ApoE3, and ApoE2 — that affect Alzheimer’s risk. “Most of us are ApoE3, we inherit it from both parents,” Crystal said. “In contrast, if you’re lucky and you inherit the ApoE2 gene from both parents, it is protective.”

But with two copies of ApoE4, he added, the risk of developing Alzheimer’s becomes at least 15 percent. Studies show that 65 to 80 percent of all those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s have at least one ApoE4 allele.

So, why does ApoE affect the risk of Alzheimer’s?

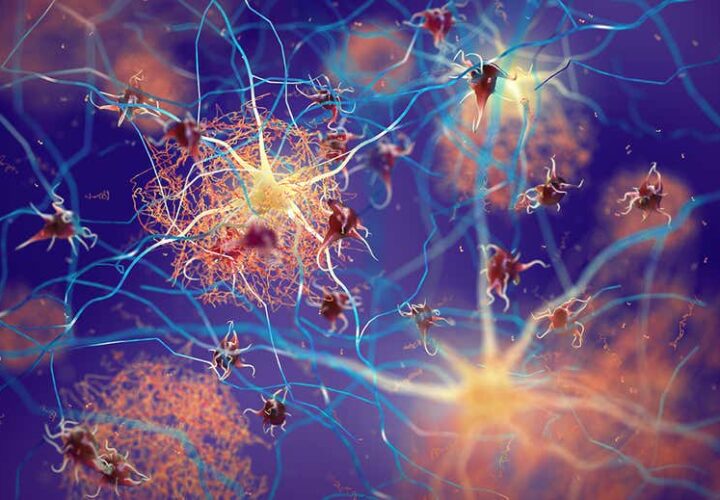

“ApoE has many different functions in the brain, all of which affect amyloid accumulation as well as tau [production] and tau tangles,” Crystal said.

Of this genes variants, ApoE4 is worse at clearing these plaques. Since it leads to more plaque buildup, people carrying the ApoE4 gene are at a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

The genes that almost guarantee Alzheimer’s disease

Other types of gene therapy may target the hereditary of Alzheimer’s which is directly caused by mutations in specific genes that ramp up amyloid production. These genes account for about one in every 20 cases.

These genes nearly guarantee Alzheimer’s disease:

- Amyloid precursor protein (APP). This protein sits within the membrane of the cell, with one end sticking out of the cell. When the end of the protein is snipped off, it forms beta-amyloid. More APP means the brain will make more beta-amyloid, eventually leading to plaque formation and Alzheimer’s.

- Presenelin 1 and 2 (PSEN1, PSEN2). These genes help form the protein that cuts the end off of to make beta-amyloid. Mutations in this gene cause it to create too much beta-amyloid leading to plaque formation and Alzheimer’s.

Each of these genetic perpetrators increase the production of amyloid plaques in the brain — a key Alzheimer’s biomarker — early in a person’s life.

How would Alzheimer’s gene therapy work?

“There’s a lot of work that’s going on throughout the world in terms of gene therapy,” Crystal says.

Many of these gene therapies work by changing the expression of a specific gene by trafficking a brand new copy of a healthy gene into brain cells or drugs that affect how much a gene is activated. These forms of gene therapy do not change the underlying genetic code.

However, new therapies in development can actually edit the DNA, with the potential to “erase” genes that increase the risk of Alzheimer’s and replace them with a healthy version.

Therapies that don’t change the DNA

Crystal founded a company called Lexeo Therapeutics built out of his lab’s research into Alzheimer’s gene therapy. He noticed that when people inherit both the ApoE2 and ApoE4 gene, the ApoE2 cancels out the risk. These findings gave Crystal the idea: Add the ApoE2 gene into the brains of people carrying two copies of ApoE4 to reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s later in life.

“We’re essentially using viruses like a Trojan horse to carry the normal gene, ApoE2, into the cells of the brain,” Crystal says. “The cells then embed the brain with the ApoE2.” From then on, Crystal and his team hope that the cells will continue to produce the ApoE2 protein on its own. “The important thing is, first, showing it’s safe and secondly, to show that you can actually get ApoE2 into the brain and that it will persist,” Crystal added. “Then, the hard part is proving that it really works, which takes large numbers of patients, and that’ll take several years.”

One of the early gene therapy trials for Alzheimer’s involved boosting the levels of ApoE2 using ApoE- boosting pills in people with moderate Alzheimer’s disease. More ApoE2 would mean more clearance of beta-amyloid proteins. However, this didn’t slow the course of the disease. Note that the people in this study already had one copy of the ApoE2 gene.

In contrast, Lexeo Therapeutics will test the effects of ApoE2 in people who carry two copies of ApoE4. The company is testing their drug across multiple trial centers in the U.S. to find out. But even then, Crystal explained that there are many other approaches scientists are trying.

“Another strategy, for example, was to try to reduce the ApoE4 in the brain,” Crystal said. “Then there are strategies many pharmaceutical companies are working on in terms of monoclonal antibodies directed against amyloid, against tau.”

Rather than receiving infusion every two weeks or every month, gene therapy would allow the brain to develop its own antibodies against Alzheimer’s.

Therapies that change the DNA

Until fairly recently, it was very difficult to edit the genetic code itself. This changed with the development of CRISPR/Cas9, a tool that makes it possible to snip out, edit and write new genes into the DNA itself. It was discovered in bacteria in 1987, but it took decades of development before CRISPR could even work in animal cells. However, it made headlines in 2016 when CRISPR was first tested on a human. In recent years, the field of genetic editing has exploded as these capabilities have developed further.

In the spring of 2020, in a mouse study, scientists in Tokyo used these “genetic scissors” to cut out genes in order to affect beta amyloid production in the brain. Just a few months later, in a petri dish study, researchers in Canada used CRISPR/Cas9 to alter a certain gene in nerve cells and, in turn, control (and slow) the production of beta-amyloid prgeotein, the protein that aggregates in toxic clumps at the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. In the future, this could treat early-onset Alzheimer’s disease by knocking out genes like PSEN1 which kickstart the disease process.

What’s next for Alzheimer’s gene therapies?

With more of these therapies advancing to human trials, Crystal emphasized that they will require participants to succeed.

“I would encourage people to think about participating in trials,” Crystal said. “These go on all over the country, and it’s really the participation of people with Alzheimer’s that make this possible to be able to develop a cure.”