A new study finds that older adults who are socioeconomically disadvantaged have greater odds of functional impairment and probable dementia after an ICU stay.

Over the last few decades, the number of older adults admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) has been rising — a trend that is expected to continue as the aging population grows. The good news is that ICU patients’ survival rate has dramatically improved during this period. But an ICU stay can be the beginning of other health issues. In fact, patients can experience new or worsening problems with cognition, mental health and physical function, — collectively known as post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) — long after discharge. For ICU survivors living with PICS, including those who had COVID-19, life just isn’t the same.

Trouble thinking clearly, muscle weakness and post traumatic stress disorder are among the different symptoms of PICS. Experts say older adults are especially prone to developing the syndrome, and pre-existing health factors can increase that vulnerability. As researchers continue to make inroads in understanding PICS, a recent study, published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, now adds socioeconomic disadvantage as a risk factor of certain PICS outcomes in older adults.

The study reported that low-income older adults had a nearly three-fold greater burden of disability after their ICU stays, compared to their more socioeconomically advantaged counterparts. The risk of post-ICU probable dementia was even higher for this group — almost 10-fold higher for low-income patients.

According to Dr. Snigdha Jain, the study’s lead author and a pulmonary and critical care physician at Yale School of Medicine, past research shows that functional and cognitive decline has far-reaching consequences for older adults and those who care for them.

“When we see cognitive and functional decline among older persons, it’s associated with increased risk of staying in a facility, so being institutionalized, because they often lose their independence to be in their own homes,” Jain told Being Patient. “It increases the risk of dying, and it increases the burden on their caregivers.”

Functional and cognitive impairment in older adults, she added, can also lead to hospital readmissions; further, these patients often require more home-based care services. For older adults who lack financial and social support, disability and cognitive impairment after an ICU stay may exacerbate their unmet needs for medical care. Ultimately, Jain’s team hopes to identify and tailor interventions that can improve health equity among ICU patients.

For the recent study, Jain and her colleagues gathered data of people aged 65 or older, patients who stayed at an ICU for a day or more between 2011 and 2017. The researchers then compared health outcomes between older adults who met the low-income threshold for both Medicare and Medicaid eligibility and those who were not eligible for Medicaid. (Dual-eligibility is a common measure of socioeconomic disadvantage.)

After accounting for sociodemographic and clinical factors, the team observed that post-ICU disability scores for mobility and self-care were 28 percent higher among dual-eligible patients, compared to those who were not eligible for Medicaid.

Dual-eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid was also linked with an increased risk of probable dementia by nearly 10 times (though it had no significant bearing on mental health issues like depression and anxiety).

Building on recent study’s findings, Jain and her colleagues are now aiming to explore whether rehabilitation could play a role in the disparities of patients’ health. In particular, they are planning to examine whether low-income patients receive adequate physical and occupational therapy following their critical illness.

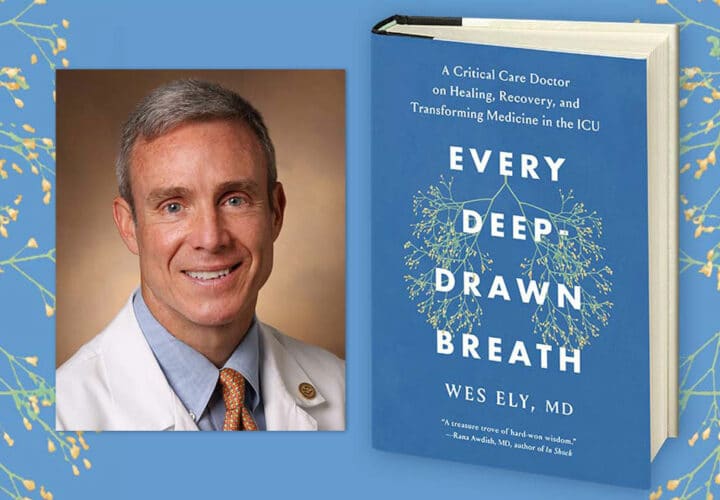

Meanwhile, Jain encouraged families to be advocates for their loved ones both during their ICU stay and after. In a past interview with Being Patient, Dr. E. Wesley Ely, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and co-director of the Center for Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship (CIBS) added that there are now protocols to optimize the recovery of critically ill patients.

Some of these include monitoring for pain and delirium, minimizing sedation and mechanical ventilation, keeping patients physically active early on, and involving family members as part of the care team. For guidance on how to support a loved one who has been admitted to the ICU, CIBS offers a wealth of resources and practical guides.