Vaxxinity’s beta-amyloid vaccine to treat Alzheimer’s disease — UB-311 — recently received fast track designation as it finishes up Phase 2 trials.

Vaccines are considered one of the greatest innovations in medical history. Immunizations help train the body’s immune system to recognize and respond to a specific pathogen or protein. Many pharmaceutical companies are now exploring whether vaccines could treat Alzheimer’s disease: As of spring 2022, there are at least nine different vaccine candidates in clinical trials.

Vaxxinity’s UB-311 vaccine — which targets a soluble form of the toxic beta amyloid protein — recently received Fast Track designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). While this designation does not guarantee that the vaccine will receive approval, it expedites the submission process.

The company plans to initiate a Phase 2b trial by the end of the year. Vaxxinity’s CEO Mei Mei Hu, 36, is on a mission to use vaccines and immunizations to “democratize healthcare” by making them more affordable, accessible and convenient.

Her parents founded UBI United Biomedical Inc., but she studied law and began her career as a management consultant. Eventually, this path led her back to her parents’ pharmaceutical company.

“Life works in funny ways,” Hu told Being Patient. “I was brought back to help with one problem, and ended up saying that there’s a lot of impact to be made here.” This spurred her journey toward developing vaccines for age-related degenerative disorders.

She spoke with Being Patient about the promise and challenge of developing an Alzheimer’s vaccine — and why, in the current landscape of treatment options, it is so critical.

From the ‘amyloid gene’ to developing safer vaccines

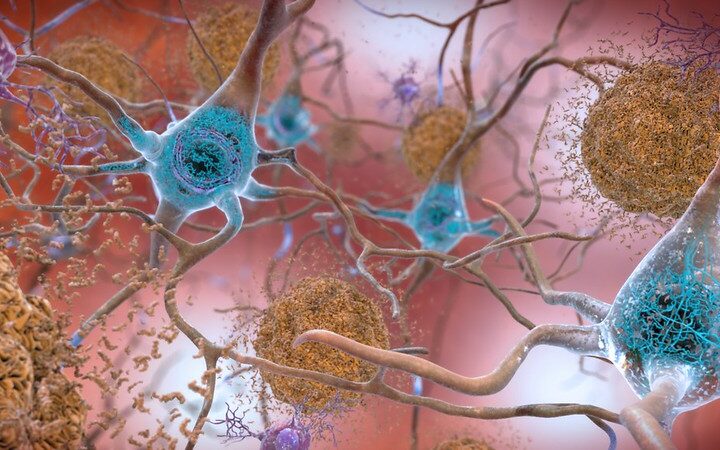

Since the 1980s, scientists have known that APP, the “amyloid gene“ and the amyloid precursor protein it generates play an important role in Alzheimer’s disease. The protein becomes misfolded as people age and begins to stick together, disrupting brain function, and often leading to Alzheimer’s. As scientists gradually came to understand more about the dynamics of beta-amyloid, they formulated strategies to eliminate beta-amyloid in hopes of treating Alzheimer’s.

By the end of the 20th century, scientists at Pfizer and Jannsen had developed the AIP 001 vaccine, a vaccine that targeted beta-amyloid. But, in 2002 the development of this vaccine was terminated due to issues with its safety profile: In Phase 2a trials for AIP 001, six percent of patients developed meningoencephalitis — inflammation of the thin membrane enveloping the brain.

But the first vaccine was led and developed by neuroscientists; Hu believed her company, Vaxxinity, and their immunologists could develop a safer treatment.

“We know how to build immune tolerance safely and generate a vaccine that induces really potent antibodies — but without the safety side effect,” Hu told Being Patient. Unlike AIP 001, she believed her company could make a safe, effective Alzheimer’s vaccine, solving the challenge of how to get immune system cells to focus solely on attacking beta-amyloid, without causing inflammation and damage to the body.

Why vaccines may be a better option than antibody treatments

The only FDA approved disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer’s disease is Aduhelm (generic name aducanumab), the controversial anti-amyloid drug created by Biogen and Eisai. However, the efficacy, safety, and, ultimately, the approval of this drug has been called into question. Further, it comes with a hefty price tag — $28,200 for patients who aren’t enrolled in clinical trials (down from twice that at the time of its approval in 2021).

There are other issues with Aduhelm, and the similar -mab drugs drugs lecanemab, donanemab, and gantenerumab.

Their endings, –mab, are shorthand for monoclonal antibodies, which are laboratory-made proteins that mimic the immune system’s defensive abilities. Antibodies are highly specific defensive proteins that bind to a part of a protein. In the case of anti-amyloid antibodies, they bind to beta-amyloid and attract more immune cells to facilitate clearance.

The difference between these antibodies and vaccines is that a vaccine also trains the immune system to recognize the problematic protein so it can be dealt with in the future. The next time the brain’s immune system would encounter beta-amyloid, it would initiate the immune response on its own.

Hu explained that antibody-based drugs are “difficult to take and extremely expensive,” adding that the average cost of this class of drugs is “$100,000 a year.” This makes antibody-based therapies difficult to scale to a large population, notwithstanding the monitoring required to manage amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, which affected more than one in three individuals taking the highest dose of Aduhelm during clinical trials.

“I don’t think there’s any antibodies right now that could serve 44 million people [with Alzheimer’s],” Hu said. “Imagine the proposition with an antibody: I’m going to ask you to go in and get infused, spend several hours of your day, every month, to get infused with an antibody. And it’s going to cost a lot of money.”

Vaccines could be administered to people before symptoms emerge, and they are more convenient, accessible and affordable than drugs administered through a series of spinal taps, Hu noted.

Not all amyloid is made equal

One of the challenges of vaccine development is directing the immune system to the right target. In the case of beta-amyloid, there are multiple different folded forms of this protein, some more toxic than others.

UB-311 goes after the soluble aggregating amyloid proteins: the sticky, free-floating forms that kill neurons.

“They’re the ones that cause a lot of havoc and are part of the [amyloid] cascade,” Hu said. She added that plaques form after aggregated amyloid proteins have already run amok.

The future of Alzheimer’s vaccines

The upcoming Phase 2b trials for UB-311 will test how well the vaccine works on individuals in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. But vaccines could eventually allow us to immunize against age-related brain diseases decades earlier.

“I think it’s a much more attractive cost-benefit profile to be going earlier and earlier in the disease,” Hu said. “Eventually what we love is a multi-combo vaccine, just like we give kids MMR today.” These vaccines could simultaneously target beta-amyloid as well as other protein biomarkers, she said.