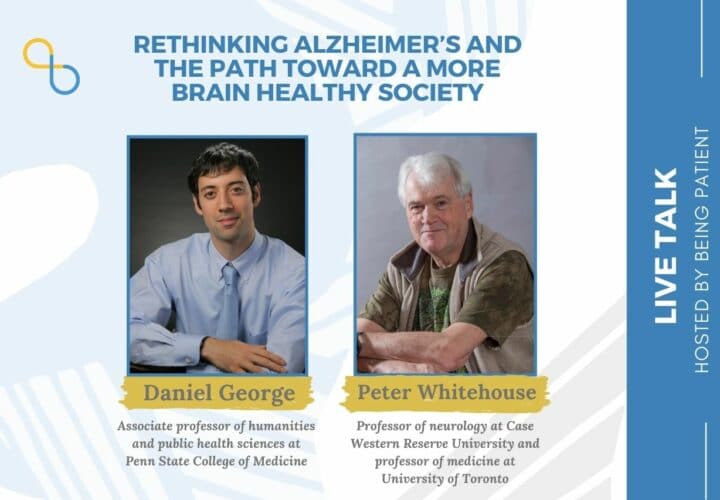

Daniel George and Peter Whitehouse, authors of 'American Dementia: Brain Health in an Unhealthy Society,' discussed the problems of seeing Alzheimer's as a single disease that can be cured, the paradox of declining dementia rates, and what we can do collectively to improve healthy brain aging and quality of life for people living with dementia.

Despite the absence of disease-modifying treatments, the dementia rate in developed Western countries has actually declined in recent years. In fact, one study showed that the incidence rate of dementia fell by 13 percent per decade in Europe and the U.S. between 1988 and 2015, meaning that people’s likelihood of developing dementia has steadily fallen.

In the book American Dementia: Brain Health in an Unhealthy Society (Sept. 2021), Daniel George and Peter Whitehouse delve into this encouraging trend, noting that improved heart health and access to education, which are closely linked with dementia risk, from public policies in the 20th century have seemed to protect the brains of today’s older adults.

However, George and Whitehouse note that today’s “hyper-capitalist principles” threaten the public health gains of the past as society faces issues ranging from poverty, to income inequality, to climate change, to access to healthcare and higher education, all of which affect our health, and in particular, brain health.

Further, they believe that society’s focus on leveraging biomedical science and free markets to cure Alzheimer’s has led us astray from addressing an inconvenient truth: Instead of being a singular, curable disease that’s separate from aging, Alzheimer’s is a syndrome that involves a host of age-related processes that unfold throughout life. So, preserving our collective brain health across the lifespan requires broad changes to institutions, communities and public policies, George and Whitehouse say.

In a wide-ranging interview, Being Patient reporter Nicholas Chan spoke with George, associate professor of humanities and public health sciences at Penn State College of Medicine, and Whitehouse, professor of neurology at Case Western Reserve University and professor of medicine at University of Toronto, about the crisis of the current paradigm of Alzheimer’s, the patterns that underlie the decline of dementia risk, and their vision for creating more brain healthy and compassionate communities.

On understanding Alzheimer’s as diseases of aging:

Being Patient: Why is the concept of Alzheimer’s as a single, curable disease that is separate from aging, in crisis?

Peter Whitehouse: As a neurologist who’s seen patients for years, I came to appreciate that the reductionistic biomedical model just wasn’t working. Why is it in crisis? Because we haven’t produced any biological interventions, and in fact, it’s in an even worse crisis because the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) approved one (Aduhelm) without demonstrating its clinical value. We’ve gotten to a point in the field where we’re desperate. We’ve been built around false hope.

(In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market indefinitely.)

It’s time we looked at the whole history of Alzheimer’s disease, and particularly the dominance of forces that drive profit and want to essentially take advantage of individuals and societies by promising things that don’t work, haven’t worked and won’t work. We need a different approach.

Daniel George: When you look closely at the history of Alzheimer’s, which is quite young for a disease, the 70s become a very pivotal decade. That’s when the war on cancer was launched and the war on Alzheimer’s was launched, and we had these large scale proclamations about curing disease. Clearly those were effective political shibboleths in terms of getting funding, shaping the markets, [and] rallying researchers around a shared goal, but we may have defined the problem wrong.

With cancer, we now look at it as multiple cancers. It’s a spectrum of conditions. Alzheimer’s disease, we would argue, and many agree, is not a singular condition. It’s [an] age-entangled syndrome that’s heterogenous and that complicates the search for a simple, single mechanism cure.

Being Patient: The amyloid hypothesis — the idea that the accumulation of beta-amyloid proteins is the main cause Alzheimer’s — has dominated the field of Alzheimer’s. But research has shown that many people with amyloid pathology in their brains do not actually develop dementia. Can you tell us more about the studies with these findings and their implications?

Daniel George: One famous study is the Nun Study. One revelation that was found in that study on several hundred nuns and has been replicated in populations around the world is that about 40 percent of normally aged people have pathology in their brain consistent with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis. But they don’t have clinical dementia: not only is this a heterogeneous condition and syndromal, [but also] the pathology is not destiny.

Being Patient: Why is the Alzheimer’s field’s focus on the amyloid hypothesis problematic?

Daniel George: For one, we don’t entirely know what amyloid does in the brain. As I mentioned earlier [about] the Nun Study, people can have plaques, which have beta-amyloid as a constituent part of them, and not have dementia.

Beta-amyloid is also a feature that we see with stress response and immune response. It’s necessary for the growth of cells and synapses. You see it in response to hypoxia and traumatic brain injury. There are people like our colleague and friend George Perry and others as well who have even proposed that amyloid could be a form of scar tissue or a brain self-repair response. But we’ve assigned it value as toxic and attacked it as if it were a pathogen.

Peter Whitehouse: There’s a single word answer also: genes. The reason amyloid got so much attention was that in very rare cases, a genetic abnormality in genes responsible for some aspects of amyloid were found. I think the lesson here is that medicine is obsessed with genes.

Well, we’re ignoring the environment and this climate crisis. There are things which we can be doing to improve the climate, the environment, the communities we live in, and that has been relatively ignored by medicine because of their fascination with the power of controlling genes.

On the reduction of dementia risk in developed Western Countries:

Being Patient: With aging populations in developed Western countries, the overall number of people with dementia is increasing. But, for people in these countries like the U.S., U.K. and Canada, the risk of being affected by dementia have actually declined in the past decades even without disease-modifying therapies. Why is that?

Daniel George: That’s really the motivating question behind the book and what gets me excited about this, because there’s such an irony here. Drugs have almost uniformly failed, yet dementia rates are declining, and out of that paradox emerged this book.

When [researchers] pull the data from all of the countries that you mentioned, what they see from the 1980s onward is a per decade reduction of 13 percent dementia risk for the cohorts that are growing older in those decades and a 16 percent risk [reduction] specific to Alzheimer’s disease.

When you zoom out and try to understand what’s happening culturally, there are two main patterns that emerge. One is that over the course of the 20th century, we got much better at treating vascular risk factors, heart attacks, high cholesterol, diabetes, and those sorts of things. Two, we provided higher education and formal education to tens of millions more people in those countries.

“Drugs have almost uniformly failed,

yet dementia rates are declining,

and out of that paradox emerged this book.”

Those things don’t just happen in a vacuum. They happen within a very particular political economic context. Specifically, after the 1930s, the world wars and the Great Depression, Western States saw fit to start investing in their populations again. There were limits put on capital mobility. There was taxation of wealth of the rich [and] corporations. That money was redistributed and used to build strong safety nets.

In the United States, we had the GI Bill, which provided higher education for tens of millions of veterans coming back. Cognitive reserve is a somewhat mysterious but very real dynamic that protects people’s brains as [they] get more education.

On the vascular dementia side, improved healthcare systems were providing better frontline care to treat vascular risk factors. We had very effective smoking cessation campaigns. The smoking rates went from 42 percent in the United States in the 60s to 14 percent today. We were able to get lead out gasoline by the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) using the Clean Air Act, and that resulted in an 80 percent drop in blood lead levels in United States citizens from the 1970s to the 1990s.

All of these collective investments from the 20th century seem to be having these downstream brain health benefits for the cohorts of folks who are aging.

Being Patient: How does poverty relate to dementia and brain health?

Daniel George: We have a whole chapter in the book dedicated to looking at that very question and we do it through the eyes of the Fight for $15 movement. These are frontline fast food workers trying to get $15 an hour [in wages]. When we know what is protected for brain health, from diet, exercise, stress, poverty reduction, to avoiding substance abuse issues and workplace injuries, it’s almost impossible to have brain health when you’re [a] working poor in this country.

Being Patient: How are the current trends worrying?

Daniel George: Things have been trending the wrong way, especially if you’re poor or [if you’re in the] working class in this country. In terms of vascular health, whereas we saw major gains in terms of treating chronic diseases and vascular disease specifically in the 20th century, we’re now seeing a tilt in the wrong direction.

According to the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), six out of 10 Americans live with at least one chronic disease. There’s 80 million [people who are uninsured] or underinsured in this country. These are people who are not getting care or getting very minimal care, not [being treated for] vascular risk factors until it’s too late in many cases. That’s unconscionable.

Real wages have been stagnant for the working class for 40 years. The Fed (Federal Reserve) released a survey a few years ago [showing] that 40 percent of Americans couldn’t cover a $400 expense without going into debt or selling something. There’s a lot of people living very precarious, stressful lives. We saw that boil over with Occupy Wall Street a few years ago and then dissipate unfortunately.

We’ve got falling lifespans on our hands. We lost a whole year and a half of life expectancy last year. But four of the five previous years, we also had falling life expectancy. A lot of that is due to poor chronic disease care, but also diseases [and] deaths of despair from alcoholism, suicide and drug abuse, which are rampant right now.

Want to learn more about clinical trials

for Alzheimer’s and dementia?

Check out the Lilly Trial Guide.

We have of course another national lead crisis on our hands. We dealt with the gasoline issue in the 70s, but now we have the crisis of lead in our drinking waters, which has been dramatized in Flint especially. But in California, Cleveland and Philadelphia, there is lead in drinking water right now and no lead levels are safe. Lead is a neurotoxin. It also raises risk for heart disease or heart attacks.

Then the last thing I’ll mention are the educational rates, which trended up in all those countries that you mentioned that are seeing dementia rates or dementia risk decline. Now, what we’re starting to see in the United States are actually falling cumulative years of education for cohorts that are now turning 65-plus. For people our age (younger generations), we’ve got massive debt if [we] want to go into higher education. It’s all underwritten by Wall Street and people are just getting priced out of it, especially men which is a real problem. There used to be a 60/40 split with men and women in college. Now it’s 40/60 men [and] women.

The needle is moving in very troubling directions on a lot of these indicators of brain health that were still favorable in the 20th century.

On the importance of “socialceuticals” for the care of older adults and those living with dementia:

Being Patient: Tell us about the Intergenerational Schools that Peter co-founded.

Peter Whitehouse: [For] the signature program … one kid and an adult [would] pair off, [and] would spend time building a relationship by sharing stories from their own lives or books in our library. Danny (Daniel) did some research that actually demonstrates our intuitions: That this would be a valuable, quality of life enhancing activity for the kids of all ages and the older adults.

“Grandparenting and those kinds of relationships

have been very powerful for the human species.

It’s time to reinvent relationships in the

community and get the generations to work together.”

Daniel George: One of the worst things that happens with an Alzheimer’s or any other dementia diagnosis is the social death, the stigma that accrues to that diagnosis. It can remove people from the community, from protective bonds [and] from social networks that we know are protective for brain health, general wellbeing and quality of life.

The Intergenerational School effectively reframes people with living with dementia as mentors within the school. Interestingly, the school used to be located two floors below a memory and aging clinic. People with Alzheimer’s on the third floor would be mentors, reading to kids on the second and first floors and in the basement.

I did a randomized control study for my doctoral research. The group that came to the school every week had significantly lower stress. They had a better sense of purpose, a sense of usefulness and connection to their community. They didn’t show cognitive improvement per se, but they certainly were cognitively stimulated and looked forward to coming every week even if they didn’t quite remember it. They sort of came to life when they knew that they were coming to the school and would get to see kids.

They can read books with children. They can sing songs with kids. They can make art projects. It’s a very horizontal type of learning model that is lifespan-oriented.

Being Patient: Can you explain the broader concept of ‘socialceuticals?’

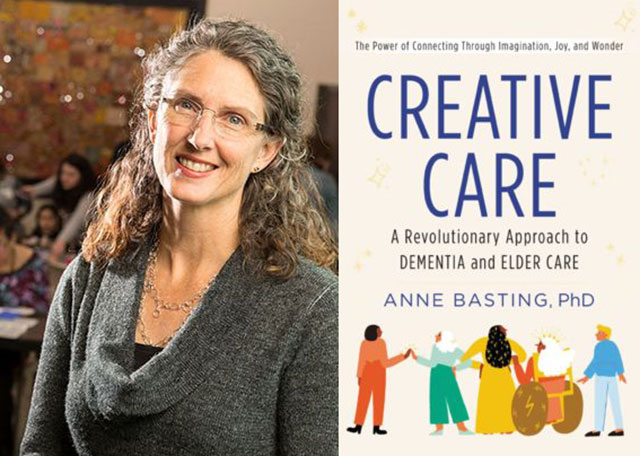

Daniel George: It’s a play on the effectiveness of art-based, relationship-based activities, like intergenerational activities, music, dance, creating artwork, telling stories. All of these things are clearly effective in improving quality of life for people living with dementia, but don’t have business models around them like pharmaceuticals do.

I have my medical students go to an assisted living home and do TimeSlips, which is a creative and improvisational storytelling project. It’s been remarkably effective not just for the people living in the locked unit at the eldercare home, but for my students who get to see people with dementia as more than just challenging patients or people with really difficult illnesses. [Students] see them as witty, insightful, playful and socialceuticals connect to something quintessentially human about us. That’s where, in my two decades of work in the field, I’ve seen the most hope and the most reason for optimism.

Juxtaposing with your great story, Nicholas, about Aduhelm being the source of hope for people: What if we had intergenerational schools? What if we made volunteering opportunities? What if we had more dementia-friendly communities? Is that maybe a better intervention [and] a better way of thinking about this very complex challenge of how to care for people living with some degree of memory loss in our communities?

Peter Whitehouse: What I used to prescribe both in Canada and the U.S. was dance, particularly intergenerational dance. Music, physical exercise, social relationships and often storytelling [are] so important. Social prescribing is real and growing.

On paving the way for a more brain healthy society:

Being Patient: What are the main takeaways of the book?

Daniel George: We need to look back. We’ve forgotten aspects of the past that have benefited our brain health — that’s part of our American dementia. Also part of dementia is not being able to project forward. So what I’d like us to do is remember the wisdom of the past and project it forward and overcome our American dementia.

To me, that means addressing this issue of 80 million [people being uninsured] or underinsured, making sure people are all getting care for vascular risk factors and other challenges in their lives. It’s [a] right of citizenship in this country.

We could provide universal education. That’s been talked about in recent years. We just need political will to do that. We could provide vocational training and adult education opportunities. We could provide a job guarantee and a living wage. We could have a national campaign to get lead out of our drinking water. We could have national long-term care insurance, as they do in Japan, where every citizen is guaranteed the right to institutional or at-home care. Lastly, we could invest in socialceuticals, like we do in other scientific and drug-based approaches.

Peter Whitehouse: The word I’m going to add is intergenerational relationships. We’ve got to work together to create communities that take responsibility for the future. Grandparenting and those kinds of relationships have been very powerful for the human species. It’s time to reinvent relationships in the community and get the generations to work together.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com

UPDATE: 3 March 2024, 9:42 P.M. ET. In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market, citing financial concerns. Although the drug did receive accelerated, conditional FDA approval for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease in 2021, it is no longer available to new patients. The company announced it would sunset trials in May 2024 and cease supplying the drug to current patients in November 2024.