The National Center for Health Statistics attributes 266,000 deaths per year to Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. Upwards of 120,000 of those per year are from Alzheimer’s, which generally ranks sixth among causes of death in that year for white Americans and fourth for Black Americans. But this year, those numbers will be notably higher.

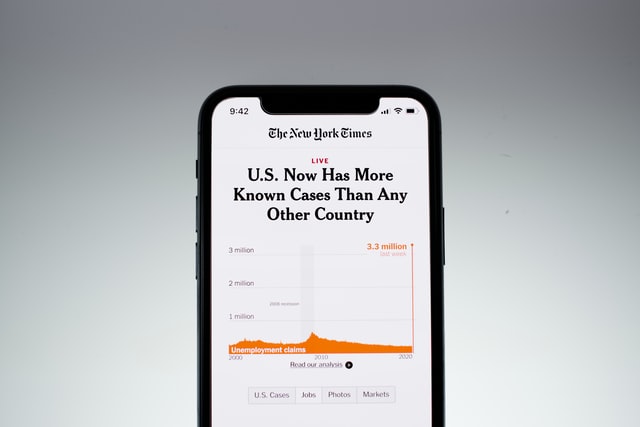

The Wall Street Journal reports that over the course of the past four months, while the world is under the thumb of the novel coronavirus pandemic, we’ve seen a surge in Alzheimer’s deaths and deaths from related dementias, in which 15,000 more Americans have died from dementias than in the same timeframe in past years — an estimated 100,000 total between February through May. According to the CDC, the death toll rose sharply in March, and by mid-April, some 250 extra people with dementia per day were dying. So far, deaths due to Alzheimer’s and dementia in California, New Jersey, New York and Texas are more than 1,000 beyond what would be normal in any other year.

So far in 2020, the dementia and Alzheimer’s fatality rate is nearly 20% higher than average from recent years.

Indeed, some of these deaths are the direct result of a COVID-19 infection, but without a positive test, the death certificate may just list the neurodegenerative disease with which the patient had long been diagnosed. On the other hand, some deaths are not directly caused by a COVID-19 infection, but still the result of the perfect storm of dementia and the circumstances of a pandemic.

Being Patient takes a closer look at just why this surge in deaths is occurring:

1. Higher Risk

Perhaps the most obvious reason that coronavirus is causing more dementia deaths is two-fold: People living with Alzheimer’s and dementia are 1) both more exposed to COVID-19, and 2) at greater risk of fatality once they are exposed to the virus.

The nation has watched as COVID-19 has swept through nursing homes and long-term care facilities like an unstoppable rising tide. Over 40% of coronavirus deaths in the U.S. have been in nursing homes. In one home in California, every resident became infected with coronavirus.

In residential care communities, more than 40 percent of residents have been diagnosed with some form of dementia. Nearly one in every two nursing home residents have. So people with Alzheimer’s or related dementias are disproportionately exposed.

They are also at greater risk once exposed: An estimated 80 percent of Americans living with Alzheimer’s are 75 or older, and older people are much more susceptible to fatality from COVID-19.

Some nursing homes have had their staff live onsite throughout the pandemic in order to reduce risk to residents, but few can afford to do so.

2. Less Accessible Medical Care

The surge in non-COVID-19 deaths during the pandemic hasn’t just befallen people living with dementia: The same surges have been documented in people living with hypertension, diabetes, stroke, coronary artery disease and others. And in a pandemic, medical care of all kinds is less accessible.

Dr. Lynn Goldman, dean of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University, believes the coronavirus pandemic will take far more lives than those lost directly to fatal cases of COVID-19 for several reasons, one being that the pandemic is preventing people from taking preventive measures or seeking needed care.

She told the Wall Street Journal, “I have friends who tell me in the hospitals where they work they’ve never seen so many ruptured appendicitis cases” — one indicator that people are waiting longer to get care.

The WSJ reports that Goldman was part the research team on a 2018 study of estimated deaths in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria. The study found that thousands of deaths that were not a direct result of the storm occurred due to power outages, infrastructural failings and lack of access to healthcare and medicine. While the coronavirus pandemic is less acute than a hurricane, factors are preventing people who need care from accessing it soon enough, if at all. During disaster events, people with any kind of health condition are at higher risk across the board.

3. Disrupted Routines, Loneliness and Anxiety

Routines and regularity are central to the mental wellbeing of people with dementia and in the midst of a pandemic, for man, that routine has been one casualty. Visits halted, and in nursing homes and care facilities where staff was cut, staff may have less bandwidth to care for each resident. Those who were displaced from long-term care or day-care programs and are now at home are also experiencing massive disruptions.

With limited caregiver bandwidth may come higher risk of accidents or declining health.

“It’s one fall, and it sets everything off. It’s one day of no fluids and they become dehydrated and it sets off a chain of events,” Indiana University’s Center for Aging Research Associate Director Nicole Fowler told WSJ. “It’s amazing how little it actually takes to upset their environment.”

Plus, the pandemic put an abrupt stop to family visits in care facilities. The has caused heightened anxiety, agitation, depression, loneliness and isolation, all of which tax the brain and can lead to a steeper decline in health for people already living with cognitive impairment.

One reason it is so difficult is because people living with Alzheimer’s or dementia often don’t understand the reasons that visits have stopped, Lori Smetanka, executive director at the nonprofit National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care, told WSJ.

“We’re hearing stories of people declining and dying literally from loneliness and feelings of abandonment,” she said.

When Ruth “Dolly” Reigel, resident of an assisted-living facility in Marshfield, Wis., stopped receiving regular visitors in March, Ms. Reigel’s daughter, Amy Cattanach said their absence quickly led to Ms. Reigel’s decline.

Ms. Cattanach argued against [the visitor ban], fearful of the separation from family. Her mother’s condition deteriorated, she seemed to lose her ability to recognize family members during their visits from outside a window, and she fell at least six times, Ms. Cattanach said. Falls can be a risk when people with dementia become more agitated, according to David Reuben, who directs the University of California, Los Angeles Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program in Los Angeles.

Ms. Reigel fractured a hip in late May, quickly developed pneumonia and died two days later. The fall was listed as the cause of death, her daughter said. Ms. Reigel’s family was able to visit in person just before she died.

“I do feel she was made more vulnerable because of not only the mental stress of not being able to be with her loved ones, but also the environment,” Ms. Cattanach said.

Senior living communities have experimented with all manner of ways to reduce isolation and loneliness, from iPads, robotic pets and Skype calls to building plexiglass walls through which family members and residents can visit and eventually allowing outdoor visits.

4. Compounded Risk In Hospitalizations

Older people hav a higher risk of being hospitalized for COVID-19, and when people living with dementia are hospitalized, they are more likely to experience delirium, which can continue to worsen symptoms and it can lead to a heightened risk of death.

Dr. Jason Karlawish, a professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and an Alzheimer’s expert, told Being Patient during a BrainTalk that this is for the same reason that worsening cognitive impairment increases the likelihood of someone dying. “You might not be able to adequately comply with your therapies and take them,” he said. “You extend the period of time that you’re in the hospital. You extend the period of time that you’re in bed … It’s one of these multi-factorial events, that sort of cascade of events, that in some cases sadly leads to death, and certainly lead to worsening disability.”

5. SARS-COV-2’s Neurological Effects

Coronaviruses can have adverse neurological effects, but we don’t yet know how SARS-COV-2 affects the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

Past studies on the neurological effects of coronaviruses indicate that the novel coronavirus and brain health are closely linked. One the one hand, it is possible that the Alzheimer’s biomarker gene may heighten a person’s risk of contracting COVID-19. On the other, some neurologists believe COVID-19 may heighten the risk of eventually developing Alzheimer’s.

Whatever the relationship, the virus’s exact impact on the brain is unclear — and this may remain the case for years or even generations to come.

Can you please send me the reference list for this article?

I am working with this population, but require literature to back up everything. You have some interesting numbers here that I would like to use, but need the citations.

Thank you for your help!

Hi Nancy, all information in the article comes from the sources linked in the text.

My father, 89, was living with Alzheimer’s in a memory care facility. He was very happy there, and he especially loved to eat. He contracted what turned out to be a mild case of COVID and after 8 days in the hospital and 2 days in a step down facility, he returned to his “home” which was on lockdown, so he was spending the majority of time alone. About 7-10 days later he refused to eat or drink. He died from renal failure on January 22, 2021. I speculate that he died from failure to thrive due to the isolation, but I don’t know whether he lost his sense of taste and smell due to COVID (although he was eating in the hospital.)

My neurologist says I have dementia due to Alzheimer’s. Need suggestions to deal with covid infection.