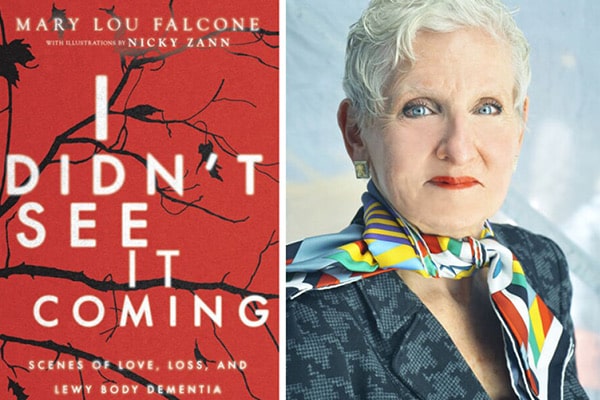

Classical music publicist, educator, performer, and Lewy Body dementia advocate Mary Lou Falcone joins Being Patient Live Talks to discuss her book, "I Didn’t See It Coming."

Lewy body dementia is one of the most common forms of dementia. Estimated to make up almost 20 percent of dementia cases worldwide, the type of dementia is characterized by problems with memory, fatigue, mood changes, and hallucinations. For loved ones and people living with LBD, the path to diagnosis and treatment is typically a long one. In fact, the Lewy Body Dementia Association found that 80 percent of participants with this type of dementia were originally misdiagnosed with something else; often enough, Alzheimer’s, as many — but not all — of the symptoms overlap. Not all cases of Parkinson’s disease are accompanied by dementia, but in the cases where someone with Parksinson’s does have dementia, it’s likely to be Lewy body.

Having navigated this journey with her late husband, Nicholas ‘Nicky’ Zann, Mary Lou Falcone decided to tell their love story to break the stigma around the disease and guide caregivers with her memoir, I Didn’t See It Coming (October 2023, East End Press).

Falcone thought she would never write a book, at least about her high-profile clients. However, “I knew in the moment that he passed what I had to write about,” Falcone explained. She knew she “had to write our love story from the standpoint of our journey, hope, and resilience, and I had to do it for other caregivers.”

For 50 years, she helped guide the careers of celebrated artists like Van Cliburn, Gustavo Dudamel, Renée Fleming, Sir Georg Solti, and James Taylor. Falcone has also advised institutions like Carnegie Hall, Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, and Vienna Philharmonic. Combining her communication skills with her background as a performer and educator, Falcone now advocates for Lewy body dementia awareness by sharing her story.

Joining in conversation with Being Patient founder Deborah Kan about the book and her journey, she shares her story of “love, loss, and Lewy Body dementia,” as well as her advice for caregivers.

Read or watch the full conversation below.

Being Patient: You have an illustrious career as a music publicist for the likes of James Taylor and the New York Philharmonic. You were a busy woman and are a busy woman. I can only imagine what it was like to have a career and then suddenly have a husband with Lewy body dementia. What were some of the first signs, and where were you in your life?

Mary Lou Falcone: The first signs were in the fall of 2016. What I saw was some forgetting, but you know, Nicky was 72, and I thought that was not too abnormal. A little paranoia, and a little bit of anger, which he never was an angry person, and repeating himself. Then, a really telling one was taking anywhere from 20 to 30 minutes to write a check.

I thought this was a little odd; maybe he’s tired. You could always make excuses for things and find reasons that you should not be alarmed. But, by the end of that year, it was in December, we were in Vienna, and he was very tired and a little foggy. One night, he was supposed to meet me and some friends in a restaurant that he knew very well. Lo and behold, a half-hour, 45 minutes pass, no Nicky. I got really frightened.

I went to try to find him heading towards St. Stephen’s Cathedral, and I didn’t know where I would look. But as fate would have it, and thank goodness for higher powers, Nicky was walking toward me. As he came toward me, what I saw in his eyes was fear. He confronted me and basically said, “You didn’t give me the address. You didn’t write it down.” He never spoke that way to me. I got very calm, and I said, “Please forgive me. It’s my fault, and I really should have done that. Let’s go to dinner.”

We proceeded on our Vienna trip, and I was there. We were there for the Vienna Philharmonic’s New Year’s concert, which was conducted by Gustavo Dudamel. Both the Vienna Philharmonic and Gustavo were my clients at the time. It became a joyous occasion, but there was a lot of doubt planted during that trip.

Being Patient: I can’t imagine that. It would be a really scary thing. I’m amazed that, without having a diagnosis or what you were dealing with, you knew how to manage that situation. Why did you do that? That’s really advanced. People usually have to learn to approach situations that way.

Falcone: There’s a backstory to this, and that is, I had been a caregiver since I was ten years old. My dad had a massive stroke when he was 37. As I said, I was 10, and I became the caregiver for my dad and for my younger brother and sister, while my mother held down three jobs to keep our family together.

“It became a joyous occasion, but there

was a lot of doubt planted during that trip.”

A child thinks they can make anything happen. What I learned in that caregiving situation was a little bit about patience, not a lot because a child thinks they can make it alright, but I began to learn how to make people feel more comfortable who could not do things that they were doing before. So, something just kicked in and said to me, “Ground, go gentle, and take the blame.”

Being Patient: It is my unscientific belief that Lewy Body is the most underdiagnosed type of dementia. When we do interviews, people tell us, “I was first misdiagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and this happened to me.” What you’re describing sounds a bit like early stages of Alzheimer’s, so tell me what that diagnosis process was like. How did you come to Lewy Body?

Falcone: It was a little bit complicated. After that session in Vienna, we went on to Paris. Unbeknownst to both of us, he had a heart attack in Paris. We should have seen the symptoms, but he was fine by morning, so we didn’t think anything of it.

Coming back stateside a couple of weeks later, it happened that he had his normal physical, which he had every six months. He said to the doctor, “By the way, what happened to that test you had me take, the calcium score test?” Our doctor looked it up, and he went, “Oh, my goodness, Nicky, we’ve got to get you to a cardiologist now.” They did a stress test, and they found out that, indeed, he had a heart attack.

They set him up with a cardiologist that everybody agreed upon, and we went to the cardiologist, [who] basically said, “Well, look, I think that you need to do an angiogram for sure, and from that will determine whether you need some pills and stents or whatever.” I went, “Oh, that’s why he’s been so kind of out of it or whatever. There’s probably not enough blood flow to the head.”

During that period, Nicky and I had been together for 34 years, and we’ve known each other for 44 years, but we had not been married. Something in me said, “Oh, something is really dramatically wrong here, and deep in my heart, I knew something was more than just the heart.” I looked at it again, and I said, “You’ve been asking me to marry you for 34 years, right on clockwork every year. Basically, I think we should do it.” He looked at me, and he had a great sense of humor. He said, “Well, it’s only been 34 years. What’s your hurry?”

We got married on the 13th of February. On the 14th of February, we went to Sinai for the angiogram. I quipped, “Doesn’t everybody go have their heart checked out on Valentine’s Day?” On the 15th, he was in surgery, [which] became a triple bypass. That was supposed to be the beginning of a new start. It was the beginning of the end because he did not come back from the hallucinations.

The hallucination started with the anesthesia, which was quite extensive, and he didn’t get stronger. He kept losing weight. Nicky was a very thin person, so he couldn’t afford to lose weight. I watched this for about a year, hoping that maybe he was just a slow healer; he was now 73. Maybe, maybe, maybe.

By 2018, we switched general physicians. Our new physician said, “You’re asking me about an MRI,” because I asked for a baseline MRI, and he said, “Let’s watch a little bit longer.” As he was watching, we were in Stockholm, and we were there for a big event that I was running. Nicky couldn’t get through the line at the airport. He didn’t know how to go through the metal detector. When we got to the hotel, he couldn’t find his way from the desk to the room.

It was sleeping all day so that at night he could be bright and with it and, all 100 percent, Nicky. Still, we didn’t know what it was, but we worked with it. We came back, and I said to the doctor, “MRI now, please. This is too much.” He did it, of course. He was wonderful.

The MRI showed age-appropriate deterioration, which to me is a nonsense phrase for “We don’t know what’s happening. We can’t tell you.” From there, our doctor, who was very kind, gentle, and smart, said, “I’m sending you to the best neurologist I know.”

“The neurologist did a cognitive test

and watched Nicky walk, and he said,

point blank, ‘This is Lewy body

dementia with Parkinsonian aspects,’

right out of the gate.”

Now, he didn’t say for what; he just said the best neurologist I know, and he sent us out of system, which is not the way they generally do things. The neurologist did a cognitive test and watched Nicky walk, and he said point blank, “This is Lewy body dementia with Parkinsonian aspects,” right out of the gate.

Being Patient: That’s amazing because many very good and competent neurologists wouldn’t make that early assumption. So, what was it? Why do so many people have such a hard time getting diagnosed with Lewy Body?

Falcone: Absolutely. But just to be sure, he then said, “I’ll do a DaT scan, and I’ll do a REM sleep test.” Now, with Lewy Body, there are three telling signs. One is early hallucinations. Another is the fluctuations, like one day or one hour, you’re completely you, and then you don’t even know who the person standing next to you is. The third thing is REM sleep disorder. That’s when, for people who don’t know, you’re dreaming, for instance, punching somebody, and you actually act it out.

The REM sleep test showed indeed he had REM sleep disorder. The DaT scan showed the alpha-synucleins, which are the Lewy bodies, which basically are rogue proteins. They’re proteins that go tangled and rogue and reconfigure. That’s why I think people can fluctuate in and out of lucidity. They don’t just damage and stay. They have a pattern to them that they take on, but that’s simplifying it. That’s basically it.

So, we were lucky. We were very lucky because [for] most people, it does mimic Alzheimer’s. It does mimic Parkinson’s, which sometimes it is also, and it mimics psychiatric disorders. That’s why it’s so hard to get a handle on it.

Being Patient: I want to talk a little bit about the hallucinations because there are people who we’ve interviewed before with hallucinations outside the norm. Don Kent, who I bring up quite a bit because I think this is just such an incredible symptom—when he ate what was salty, it tasted sweet, and when it was sweet, it tasted salty. He went to six neurologists, and no one diagnosed him. The Mayo Clinic finally said, “That’s a hallucination. You have Lewy Body.” In Nicky’s case, what were the hallucinations like?

Falcone: With Nicky, it manifested itself in an interesting way. First, it was audio hallucinations. Nicky had been a rocker in the 1950s, a rock’n’roll teenage idol, and on the same stages as Johnny Cash, Patsy Cline, and Jerry Lee Lewis—so he was for real. Music was very important to him, and audio was very important, although he was losing his hearing. That’s also a symptom of all this.

He said to me, after he was diagnosed, the day he was diagnosed, “Do you hear the voices coming out of the faucet?” I said, “No, but I know you do.” “Do you hear the music coming out of the pillow?” “No, but I know you do.” That’s how it was manifesting itself early on.

Then, there were visual hallucinations. You know, the little animals. I remember one when he told me he woke up from a dream, and he was looking around the room. I said, “What is it?” He said, “Well, there are squirrels running all around the room, and they’re running under you. I have to go into the living room and check to make sure that they’re not there. I think we need to buy a $17,000 bed to replace the bed we’re in.” It wasn’t malevolent, but it was weird.

Being Patient: How long did he live with Lewy Body?

Falcone: From diagnosis, it was 16 months, which is very fast.

Being Patient: I’ve never heard of anything so fast. Is there any explanation why some people can live with Lewy Body for years and years, and for others, it goes that quickly?

Falcone: I don’t think so. It’s the longest case that I’ve heard of. Norma Loeb, who runs the Lewy Body Dementia Resource Center, [said] her mom had it for 18 years. Nicky’s is one of the shortest cases I’ve ever heard. I think that’s [because of a] couple of things.

“From diagnosis, it was 16

months, which is very fast.”

His first year, he was pretty strong. He was able to hold his own, and it was okay. Then, in the second year, in the last five months or so, the pandemic hit. I think that caused an isolation that was necessary. With that isolation came some cocooning. We were able to come home, which was a beautiful thing, in many ways. You know, it doesn’t all have to be doom and gloom. It can be beautiful moments, and there were.

As a matter of fact, when Nicki was diagnosed in March of 2019, he said three things to me. The first was, “I’ve always wanted to meet your father, and now we’ll have my opportunity,” which was his way of telling me he knew he was dying. The second thing he said, and I live by this every single day, is, “We have had a great run. We cannot be sad.” The third thing which touched my heart, and I worked very hard to maintain it, and I’m proud that I could, was, “Please, Mary Lou, help me to keep my dignity,” and that’s very important for caregivers, too.

Being Patient: I absolutely, 100 percent agree. I think about this with my own mom, but how do you do that?

Falcone: You put on, like the Italians say, “La bella figura,” the beautiful face, but you have to believe it— because the person who is across from you feels what you’re feeling. They may not be able to articulate it, they may not be able to understand it, they may not even be able to speak at that point— but I believe that your loved one is in there and feeling. The kind touch, the touch on the face, the kind word, the loving kiss, whatever it is, really does make a difference. I’m not saying it’s easy because it’s not.

When the going gets rough, you need to take a deep breath and leave the room, and go someplace where you have a pillow waiting into which you scream. I think that if you say heck, damn, darn, it doesn’t do it. I would scream the F word at the top of my lungs into this pillow because there’s something that gets released. Then I would take a lavender sachet, and I would take one of those yoga breaths and inhale. When I calmed myself, I’d go in and greet Nicky with a big smile and a hug because it’s not his fault. Nobody asks for this. Who would?

“When the going gets rough, you need to take a deep breath and leave the room, and go someplace where you have a pillow waiting into which you scream.”

Being Patient: Absolutely. That is such great advice. Tell us a little bit about why you felt the need to write I Didn’t See It Coming. What do you want to accomplish by publishing this book?

Falcone: I’ll preface this by saying I was the person who, for 50-some-odd years, would say whenever I was asked, “Are you going to write the book,” meaning the tell all about my clients, et cetera, and the answer was “Never. I am never writing a book, period, the end.” But, about three months before Nicky died, he looked at me one day in one of those lucid moments and said, “Mary Lou, you have to write,” and I thought to myself, “Write what?” Then he passed, and I knew in the moment that he passed what I had to write about. I had to write our love story from the standpoint of our journey, hope, and resilience, and I had to do it for other caregivers.

Because when I went to our very brilliant neurologist, who got the diagnosis right out of the gate, for which I am grateful, and I asked my questions, “What can I expect? What is this going to look like?” He wouldn’t answer me. Not one word except to say you’re going to find more out from people who are dealing with this than you will from anybody else. In that, he was correct. I still think he could have been a little bit more forthcoming.

Being Patient: Do you think he wasn’t telling you because he just didn’t want you to know or he didn’t want to make you depressed?

Falcone: No, because a friend of ours had died of Lewy Body dementia three years before this diagnosis. When I talked to his widow, she asked me who our neurologist was, and I told her, and she said, “Oh, you’re so lucky. He was ours, and he walked me through every step of it.”

I went, “Wait a minute, are we talking about the same person?” We were. So, she had guidance all along the way. By the time I got to the same person, there was no guidance. Something happened. I can only speculate, and that would not be fair because I don’t know. But something happened to this man between the time she had him and I had him.

Being Patient: I mean, what you’re pointing out and not pointing fingers at anyone, but we hear this over and over again. A lot of your experience with a diagnosis has to do with that type of communication with your doctor. You want to become closer to your doctor. You don’t want your doctor to just give you this news and not guidance.

Falcone: Thank goodness for our general physician, who I will name, it was John Cahill, and Nicky called him the angel because this is a man who had such compassion. His sister also had been diagnosed, and his young sister, in her late 40s, had been diagnosed with early onset Lewy Body dementia. So, he knew what he was looking at, and he knew what it did. He was a blessing, no question about it. We were lucky. We were just very lucky with him, so I do count my blessings.

But going back to why I wrote this book, it was to give caregivers a guideline. And why did I write it the way I wrote it? Because I had front-loaded the whole thing with Lewy Body, that was my reason for writing this book. A very brilliant editor said to me, you have to tell your story, your Nicky’s story, because unless we care about you— you are never going to get us to care about Lewy body dementia, and she was right. I rewrote, rewrote, and rewrote, but finally, I got it where I wanted it, which was to write it as a narrative, as a story of our life, my life first, and then when Nicky joined my life, and what our what our journey was.

Being Patient: It’s a love story, right? You write it like a love story.

Falcone: I do, because what you remember are stories. What you remember are, yes, the sad parts, but you remember the happy parts too. I really did want to point out that there’s a lot of joy in the agony. There’s both.

Being Patient: I so respect that you say this and believe you, but I think that most people aren’t like you. I think it’s very, very hard to get to that space. I see it within my own family— that’s a hard thing. You seem very positive, and you know intuitively how to preserve your relationship with Nicky.

Falcone: Remember, I had a role model called my mother, and nobody had a harder life than my mother did. I won’t go into the details, but my father’s illness alone. She was 38 years old; he was 37 years old— the prime of their lives.

“I really did want to point out that

there’s a lot of joy in the agony.

There’s both.”

They misdiagnosed my dad when he had a stroke. He lived, but he never spoke again for the rest of his life. And to watch them communicate, to watch this, you just have to, at least I had to, embrace that as something to emulate. Maybe I’m not normal. I would say that it’s something I work at, to be positive. I do deflect negativity. I have my whole life. I prefer to dwell on the positive, and I’ve made that a mantra.

Being Patient: That’s the best way to live and makes for a long, happy life. Can I ask you a little bit of a difficult question? I’m asking you this because it comes up from our community of readers. How does someone die of Lewy Body dementia?

Falcone: That’s a very good question. In Nicky’s case, remember there was also Parkinson’s present, so the walking became difficult, and finally, a wheelchair had to be employed, which I called the chair with wheels because I refuse to call it a wheelchair in his presence. [Then], he was having trouble with his hands. He couldn’t hold a fork. He couldn’t cut.

I remember one dinner we went to with a whole group of friends, and my colleague sitting next to him noticed that he was having difficulty cutting, and therefore she just reached over very gently and cut up his meat. So, there was that. There were swallowing issues. Swallowing became hard. There’s incontinence, bowel incontinence, and urinary incontinence. It just happens because your muscles will not function as they had.

In those instances, I would just say [that] he gets so embarrassed and so upset. I would say, “That’s what washing machines are for. Don’t worry about it, it happens. We’ll make it right.” Meanwhile, you want to tear out your hair because the mess is the mess. But that’s what you do. Toward the end, the lucidity with Lewy Body comes in and out, as I said before, and Nicky wrote a poem about a month, a month and a half, before he died, which I found three months after he passed.

This poem described his descent into Lewy Body, what it felt like from his perspective. Now, he had been a writer, also for Esquire magazine, he was a real writer as well as his other great talents and [career as an] artist, et cetera, but this poem was so powerful. As I watched him decline, there were days when I would say, “Nicky, do you know who I am?” And he’d say, “No, but that’s all right.” Or we’d always sit at the dinner table, even when he couldn’t walk, we’d come in, and just so we’d be together. At the end of dinner, I knew he couldn’t stand up. I would reach over, and ostensibly to hug him, but to lift him as I was hugging him, and we had a ritual, and it worked.

At the end, he made a choice, a week before he passed, to stop eating. He just stopped, two bites of chicken salad that particular day when we were visiting with his favorite godchild, who was three years old, and his niece. He stopped, and I was told by a nurse friend of mine [that] when that happens, offer, but do not force. Two days later, he stopped drinking, no liquids, and would not take anything. You take a wet sponge and just make sure that everything keeps lubricated, but that was it.

When that day came, it was a Thursday, and he died on a Tuesday. So, he was four or five days away from passing. When that day came, I called all of our close relatives and close friends to come over to say their goodbyes, and they came that evening and they said their goodbyes, they went into the bedroom. He was bedridden but came back into the living room. I heard a voice, and it was Nicky from the bedroom, so I went in and I said, “What is it,” and he said, “I want to get up and go into the living room.” Clear. I said, “Fine,” put a robe on him, and took him into the living room.

“In that second, he was gone, but it wasn’t

horrible because I knew he chose in his moment.”

Deborah, I’m here to tell you that he said goodbye by name and thank you to everybody in that room. Then looked at me and said, “I’m very tired. I have to go back to bed.” And that’s how it ended. When he finally took his last breath, I was holding his hand. My phone pinged, and I looked away for one second. In that second, he was gone, but it wasn’t horrible because I knew he chose in his moment. I just know in my heart.

Being Patient: That actually is beautiful, the way you describe it.

Falcone: It was. Of course, you’re sad, but with Alzheimer’s, with Lewy body, with any of these dementias— you’re dying a little bit every day, and so is your loved one, just watching this. So, when the end finally comes, there is a rejoicing that the agony is over.

Being Patient: Absolutely. When we have a loved one with dementia, we just pray that the end is not painful. I think that that is what weighs on me.

Falcone: I don’t think it is. Hospice is wonderful, and they bring in the end-of-life kit, and the morphine is there, and the morphine helps. They also ask you if you want an oxygen mask, and instinctively I said no. But then I called our doctors and [asked] if I should have said yes, and he said, “No, you’re right. Your instinct was right,” because I felt that anything on the face, anything that was intrusive, would actually be negative, not positive.

Being Patient: After writing this book, how do you want people to remember Nicky?

Falcone: I want people to remember Nicky as he was described in the hundreds of condolence letters that were sent to me, which is, [that] he made us feel like the most special person in the room with his love, with his kindness, and with his generosity. That’s the Nicky that everyone remembers and misses.

Being Patient: What a beautiful story. I Didn’t See It Coming is available for purchase on Amazon. Thank you for sharing the story. These types of interviews and books are so helpful to people. Thank you for writing about it. It’s really important.

Falcone: Thank you. Thank you very much for the opportunity to share. One last word and that is to all caregivers out there. Please know, [that] even in your loneliest moments, you are not alone. That’s why I wrote this book to make that message clear.

Katy Koop is a writer and theater artist based in Raleigh, NC.