In the UK, over 25,000 people from ethnic minority groups are living with dementia. Through his organization Meri Yaadain, dementia researcher Mohammed Akhlak Rauf has set out to research – and remedy – why the country's healthcare system is failing them and their carers.

This article is part of the series Diversity & Dementia, produced by Being Patient with support provided by Eisai.

As young kids growing up in West Yorkshire, England, Mohammed Akhlak Rauf and his siblings giggled innocently when their grandmother swore, one of the signs of her undiagnosed dementia. Today, he knows this was no laughing matter.

“Speaking English wasn’t a problem for my dad, but nobody ever defined dementia for him,” Rauf told Being Patient of his father’s journey as a carer. In fact, witnessing the many challenges faced by his immigrant parents in navigating dementia care eventually led to him establishing Meri Yaadain.

In 2006, Rauf embarked on a two-year project to explore the impact of dementia on South Asian families. But the project would sprawl far beyond those bounds, gaining national recognition. A decade after its inception, Rauf earned a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) from the Queen in recognition of his services.

Meri Yaadain registered as a community interest company three years later, allowing the organization to enhance both its geographical spread and the type of services it offers, now raising dementia awareness among other ethnic minority communities.

Overcoming language limitations, one generation at a time

According to Rauf, the name Meri Yaadain translates to ‘my memories’ in the Urdu language, reflecting Rauf’s roots — his parents left Pakistan for the UK in the 1960s. Today, the organization is rooted in advocating for those seldom seen in the dementia narrative.

“We don’t have a word for dementia, nor do we refer to ourselves as ‘carers,’ making it a challenge for healthcare service providers,” Rauf told Being Patient. In his line of work, language limitations present in more ways than one. “I’m first generation, so I’m trying to understand the older generation, as well as working with my generation and my kids’ generation,” he said. “As communities evolve in their world view, language becomes crucial. Unless you can actually understand what dementia is, how do you relate to its symptoms?”

Even UrduPoint, a reputable Urdu-language web portal, lists ‘derangement’ and ‘insanity’ as synonyms of dementia.

“If there’s no word for the condition, I say let’s normalize the word ‘dementia’ in the way we’ve normalized ‘cancer’,” he said. “The other aspect of language is that as communities transition, going from immigrants to those who were born and educated here, we have to understand the shift from Asian cultural values to Western social norms. And moving someone into a care home is a prime example.”

A lack of understanding about the disease leads to stigmatization of the people experiencing it, and that leads to belated diagnoses and lack of access to care, Rauf said. “People then associate those symptoms with madness, which brings the stigma that prevents our communities from accessing the support they need.” These are some of the issues Meri Yaadain has set out to resolve.

While Rauf’s parents couldn’t fathom moving his grandmother into an assisted living facility, his generation may at least be open to receiving support. “My mum would insist that it was her ‘duty’ to care for a parent, whereas I may seek some support while choosing to care for a parent at home,” Rauf said. “In contrast, my son might simply accept that he can’t cope as a carer, at peace with the fact that moving me into care doesn’t make him any less of a Muslim. Because our thoughts change, language is important in terms of knowing the concept, the symptoms, and what can be done about the symptoms. But that’s the academic side of things.”

Taking an academic approach to supporting South Asian carers

Recently, Rauf earned a PhD from the University of Bradford, where he researched the transitions relating to distress among South Asian families in which someone is living with dementia. The process of working with countless families to break down cultural taboos piqued his interest in the academic perspective, leading him to connect research with policy and policy to practice.

“When communities transition, service providers are not necessarily on the same journey. Services may say, ‘Our doors are open, so come over if you want some help.’ There’s equality in the sense that their doors are open for everybody. Equity is a different thing altogether,” asserted Rauf. “If I don’t know you exist, even though your doors are open, how do I get to you? I need to have adequate information about something before I can get that help. That’s why I studied how informal carers cope with the complexities of advancing dementia. How do these unpaid carers manage? Do they call for services? Do they turn to community groups? Do they use their faith?”

His research as a doctoral student revealed that many carers don’t see themselves as such, thereby politely declining any outside help. Those who acknowledge their role as a carer, meanwhile, may pursue an assessment and seek welfare benefits such as home visits by social services.

Highlighting an outdated system that has failed South Asians

Another area of research was the quality of the support itself.

“The reality is that services are often unable to provide culturally competent support to diverse communities,” he emphasized. “Even if their doors are open, would I put my mum there if the sights, the smells, the people, the images on the wall don’t fit my culture?”

Echoing his sentiments is a 2021 report that found the UK’s healthcare system — essentially designed for white British patients — is outdated, leading to inequalities in diagnosis and support. It’s also unequipped to cope with the predicted eightfold increase in dementia rates among ethnic minority communities over the next 30 years.

Rauf reports of a South Asian carer who had to get a fatwa (a ruling on a point of Islamic law) from an imam to access respite care because his relatives were adamant that it was his duty to care. And when he approached a respite care service, they were dismissive. Rauf recalled them asking: “Shouldn’t you be looking after your mum at home? Isn’t that what your families do?”

It is for such reasons that Rauf urges respite care to stop holding onto preconceived notions, and start becoming culturally competent in their services instead. This includes providing the appropriate information in languages spoken within the South Asian community, he said. For example, the Alzheimer’s Society has found that if someone who speaks English as a second language is living with dementia, they will revert back to their mother tongue as their condition progresses.

It also means steering clear of assumptions when it comes to serving meals, which don’t necessarily translate to halal food for Muslims, and vegetarian meals for Hindus.

The right choice of music, he explained, can elicit positive emotions in those with dementia.

“But music isn’t just about instruments,” he points out, “so a culturally competent service would understand that the rhythm within recitation of the Quran can act as a calming influence.”

Impacting the big picture in dementia care

On a broader scale, Meri Yaadain also works to highlight ethnic minority experiences of dementia among statutory organizations, working at policy level with the likes of Alzheimer Europe and All-Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia.

Addressing aspects like engagement, it has guided researchers on how to recruit minority community participants, encouraging them to work in partnership with patients and the general public from South Asian communities.

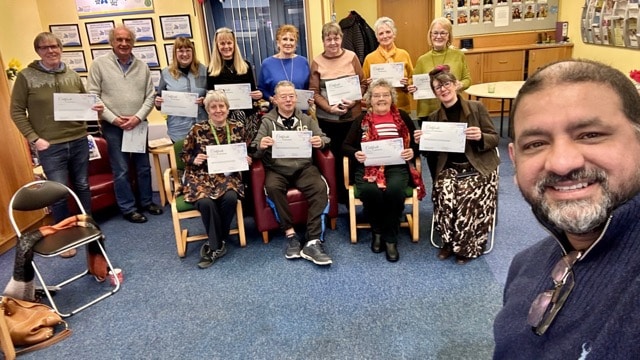

Today, Rauf is a BAME dementia consultant, providing resources to improve the quality of life and care for Black, Asian, Minority and Ethnic (BAME) people living with dementia and their carers. He and his team at Meri Yaadain also lead training sessions around cultural competency, getting practitioners to question how their bias impacts the care they deliver. With challenges on multiple fronts, Rauf said simplicity is key.

“The biggest lesson we’ve learned is the importance of understanding how a particular community engages with access to information — whether that’s a village in rural Pakistan or a big city in Australia,” he said. “Things are quite jargonistic in our field, but what’s effective is using common sense. Person-centered care starts with asking: Who is my community? What do they need? And who is going to provide it?”

Samia Qaiyum is a travel and wellness editor based in Dubai, currently writing for the likes of Reader’s Digest and The Travel Almanac.