Scientists hope a simple new kind of test could make it possible to catch Alzheimer's while there's still time to treat it. The idea is going to make some people squeamish.

There are a few new drugs out there that can actually slow down Alzheimer’s disease. But, by the time around half of Americans get their diagnosis, it’s too late to intervene. In most cases, only patients in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease qualify for clinical trials or new disease-modifying treatments like Leqembi. Scientists are searching high and low for new ways to identify Alzheimer’s earlier.

And some are asking: What if the secret to an early diagnosis is being flushed down the toilet?

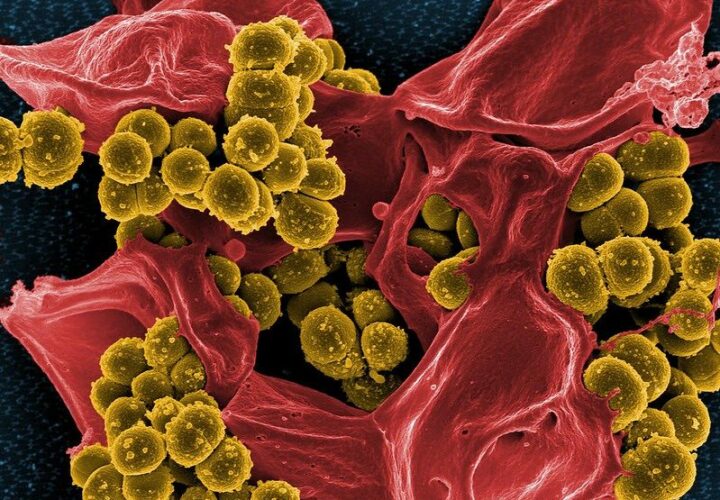

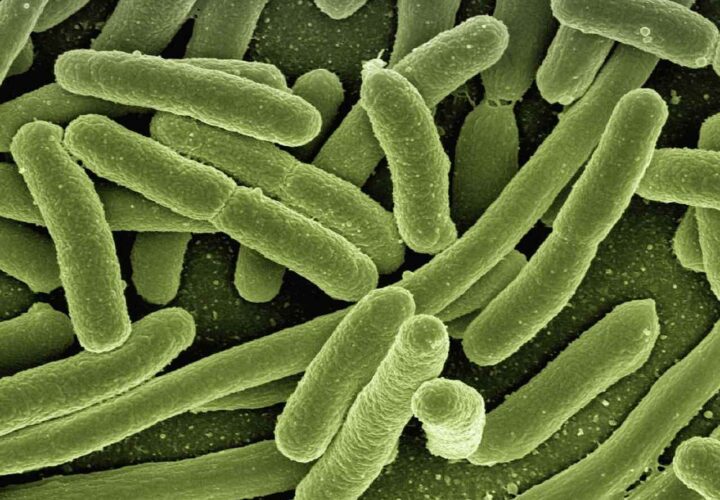

Certain bacteria found in poop could be the earliest predictors of Alzheimer’s disease. The bacteria and other microbes found in poop provide a snapshot of the gut microbiome — the trillions of fungi, bacteria, and viruses living in the colon that are important for gut and immune health.

“We are really in the early and emerging days of gut microbiome research in Alzheimer’s disease,” Barbara Bendlin, professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told Being Patient.

Meanwhile, researchers like Gautam Dantas, a Washington University School of Medicine professor, believe that microbiome testing could one day be a promising screening tool for doctors. His latest research suggests this goal might be plausible.

Is the first sign of Alzheimer’s disease in the feces?

The gut microbiome changes and evolves throughout life. Some bacteria are essential early in life, while other microbes establish a permanent abode in the gut during adolescence or adulthood. Several studies have compared the microbiomes of healthy adults with those who have dementia, finding unique bacterial signatures in each group.

“In the case of Alzheimer’s disease, we found in our human studies that the abundance /[number] of certain bacteria were associated with the amount of brain pathology we observed, even among people who did not have symptoms of dementia,” Bendlin said. “However, disease is also likely to affect the gut, and it may even be the case that changes in the gut could be an adaptive response to disease.”

But could there also be changes happening before any brain pathology? Dantas and colleagues were the first researchers to study people at risk of Alzheimer’s disease based on family history or genetics, using a cerebrospinal fluid test and brain imaging to look for Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Their study included 164 older adults with 49 participants in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease.

“In those [at-risk] individuals compared to healthy controls, we saw these differences in the microbiome,” he told Being Patient, adding that they appeared before beta-amyloid or tau proteins in the brain.

Dantas thinks that with more research and development, this could eventually become a screening tool for patients.

“You could test people at high risk more frequently through a simple stool test,” he said. Patients who test positive on this test will be monitored more closely and may be referred for a lumbar puncture or amyloid PET scan for a definitive diagnosis.

Looking to gut bacteria for Alzheimer’s clues

Dantas and his colleagues are planning a larger study to see how well microbial signatures predict Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive symptoms. This study will involve tracking a large group of patients for five years, taking several poop samples along the way.

They will also be eavesdropping on the gut bacteria to see what chemical signals they might send or receive from the brain. How does this technique work? While a spy intercepts radio signals and encrypted messages online, a microbiologist looks for tiny chemical messengers in poop — arguably the more exciting form of espionage.

“There are likely changes in the presence of important small molecules that have signaling capabilities in the brain,” Bendlin said, adding they may provide important insight into Alzheimer’s.

In addition, this study could also help scientists answer why some people who develop beta-amyloid and tau biomarkers never develop Alzheimer’s. “Might they have some special features in their microbiome that might be contributing to the suppression of the symptoms, and then opens up this possibility of the microbiome actually, itself being a therapeutic target in maintenance of therapy,” Dantas speculated.

Alzheimer’s poop tests coming soon?

Anyone can send a small fecal sample to a laboratory for a few hundred dollars to see what microbes might be living in the gut. But Dantas doesn’t think anything actionable can be done with this information — scientists aren’t ready to say that certain gut microbes are biomarkers of the disease yet. “What do you do with that information? I’d argue you could do nothing but probably stress yourself out,” he said. “We need a study like ours to be replicated by [other] people who are not at all involved with us.”

These findings may not apply to people living in other regions of the world or elsewhere in the United States. Most microbiome research isn’t conducted on a diverse population of participants, as people living in other areas have substantially different gut microbiomes. “More work is needed to include larger sample sizes and greater geographic representation,” Bendlin added.

Bendlin points to blood tests, existing accurate tools for detecting and diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease — and will be widely available to doctors in the next few years.