Professional soccer players may have a much higher risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases like dementia, Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s than the general population, a 2019 study found.

When it comes to traumatic brain injury and the link to brain disorders like chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) or Alzheimer’s, researchers have primarily focused on the impact of contact sports like football or hockey.

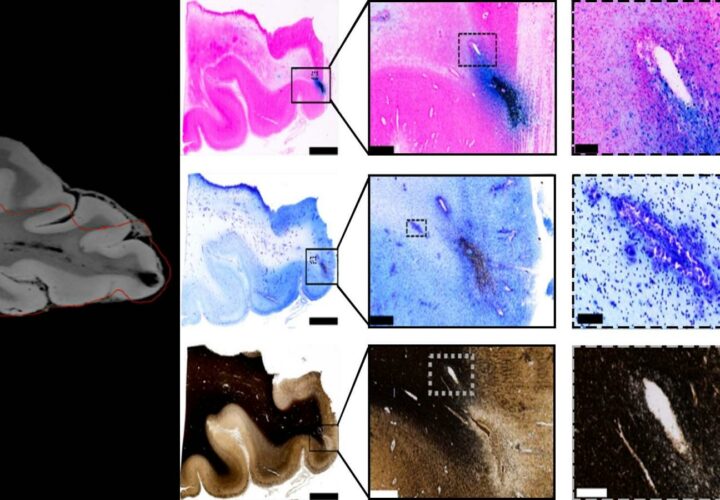

Football, which is perhaps the one sport most likely to damage a player’s brain during tackles and hits, has been shown to physically change the brain. And in a major study published a few years ago, researchers found that of 111 deceased NFL football players, 110 had brains showing signs of CTE.

But research is beginning to show that other sports, like martial arts or soccer, may be just as dangerous.

In particular, the “heading” involved in soccer—when players hit the ball with their heads—can contribute to traumatic brain injury and neurodegeneration that occurs over time in the aftermath.

The new study is the largest to examine the impact playing soccer has on dementia risk. Published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the study analyzed 7,600 medical records from Scottish men who played professional soccer. They then compared the health profiles of the soccer players to 23,000 men from the general population.

Soccer showed to have some protective benefits when it came to certain chronic diseases, like heart disease and cancer.

But the game proved to be harmful when it comes to the brain. Researchers found that the soccer players in the study were three and a half times more likely to die from neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease than people from the general population. In particular, players had a five times higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s, and double the risk of Parkinson’s.

Repetitive hits to the head, which can cause concussions or sub-concussive damage, has been shown to be largely associated with an increased risk of neurodegenerative diseases. In soccer, heading appears to be the main culprit.

“Until there is meaningful change across sport, we must assume that the risk remains real,” Willie Stewart, neuropathologist at University of Glasgow and lead author of the study, told The Washington Post.

Could you provide a link to the New England Journal of Medicine study please?

Yes you can find the study here: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1908483?query=featured_home