Through experimental AI, physicians can speed up Alzheimer’s diagnosis through a single brain scan. This technology, its makers say, doesn't require a human to weigh in.

The earlier someone receives an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, the more time they have to plan with their family and doctors. It means that the person can participate in clinical research that may help prevent or slow the symptoms of the disease, or simply allow them to start treatment early. The problem is, diagnosis is tough, when so many different forms of dementia serve up similar sets of symptoms. It might take a neurology team a few months — even a year — to issue a definitive Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

To speed this process up, the last few years has seen researchers developing new tools to make a diagnosis sooner: innovative blood tests, new types of cognitive tests, even retinal scans. Now, scientists have published a new study in Communications Medicine showing the potential of a computer model to detect Alzheimer’s disease with higher or comparable accuracy to previous models. This model however, doesn’t require any previous information about the patient, basing predictions off of a single scan.

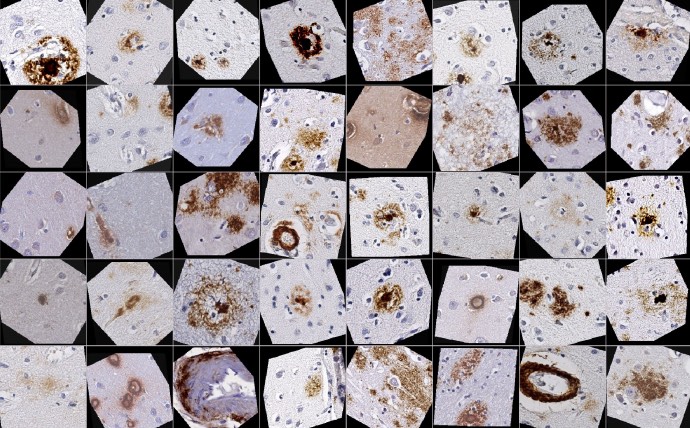

In the study, researchers trained a computer model on a dataset of 400 different MRI brain scans from people at different stages of Alzheimer’s, including healthy controls as well as people with other forms of dementia or neurodegenerative disease. After training their model on this dataset, the researchers tested it on brain scans from 80 people who underwent diagnostic testing for cognitive decline and different forms of dementia at a hospital.

Normally, brain scans are analyzed by special neuro-radiologists that look for tell-tale signs of Alzheimer’s. The researchers compared the model’s diagnosis to the bevy of tests, including brain scans and cognitive assessments, at a hospital. They found their computer model could diagnose Alzheimer’s disease accurately 98 percent of the time and distinguish between early and late stages of the disease 79 percent of the time — though this was based on the limited 83 person cohort. This technique has not been tested head-to-head in other memory clinics or studies.

Surprisingly, the computer model of Alzheimer’s developed in the study outperformed traditional biomarkers, such as amyloid levels in cerebrospinal fluid. Instead, the model zeroes in on the brain’s architecture and identifies features that a radiologist might not be able to spot on their own, such as specific changes in the cerebellum, a brain region associated with motor coordination, or in the ventral diencephalon, which aids in vision and hearing.

The study was led by professor Eric Aboagye, from Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust.

“Currently no other simple and widely available methods can predict Alzheimer’s disease with this level of accuracy, so our research is an important step forward,” Aboagye said in a press release. “Many patients who present with Alzheimer’s at memory clinics do also have other neurological conditions, but even within this group our system could pick out those patients who had Alzheimer’s from those who did not.”

Is AI for Alzheimer’s diagnosis ready to be deployed?

Don’t expect this computer model to be used in memory clinics just yet. While the results of the study are impressive, the computer model in the study was developed and tested on a relatively small sample. It is unclear whether this data came from a diverse set of participants. As a result of a lack of diversity, other diagnostics — blood tests and cognitive tests — often don’t perform well in people of other ethnicities.

Alzheimer’s Research UK Head of Research Dr. Rosa Sancho noted the promise of this technology, but she added that the computer models take a lot of “computational effort” to run, meaning they require extremely expensive, powerful computers. In order for this technology to see widespread adoption, it would need to be made more efficient so that less powerful computers can also run the diagnostic, she said.

Other researchers, like professor Rob Howard of University College London expressed caution with relying on this technology for making the diagnosis. “A diagnosis of dementia is life-changing and should always be made after consideration of the patient’s history, the clinical examination and the results of tests such as brain scans,” he said. “Over-reliance on brain imaging has been shown to be associated with dementia misdiagnosis and I have learned to be cautious with patients who tell me that their dementia was diagnosed from a brain scan.”

Nonetheless, Aboagye notes that one future hope for the computer model is that it could prove useful in quickly singling out patients who may be at a higher risk. “Our new approach could also identify early-stage patients for clinical trials of new drug treatments or lifestyle changes, which is currently very hard to do,” Aboagye said.

What else can computer models tell us about Alzheimer’s?

In the future, machine learning algorithms could be used alongside other diagnostic tests to detect and diagnose Alzheimer’s faster, minimizing the time patients and their families need to wait before receiving a diagnosis.

Paresh Malhotra, a consultant neurologist at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust said in the news release: “Using an algorithm able to select texture and subtle structural features in the brain that are affected by Alzheimer’s could really enhance the information we can gain from standard imaging techniques.”