Neurologist Marwan Sabbagh dives into how our genetic make-up — like the presence of a genetic variants such as ApoE4 — can impact not only our risk of developing Alzheimer's disease, but our risk of side effects from Alzheimer's drugs, and scientists' understanding of the disease at large.

This article was made possible through sponsorship by Alzheon. Being Patient’s editorial team produced the interview with no review/approval process by the sponsor.

Alzheimer’s treatment and prevention can depend on our genes. While the cause of the neurodegenerative disease is still unknown, mounting research shows that carrying multiple copies of specific genes — like genetic variant ApoE4 — can significantly increase the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s. By studying genetics and gene therapy, scientists are learning more about how genes play a role in Alzheimer’s disease and prevention.

But what does this research mean for people with a family history of Alzheimer’s or who have a genetic predisposition?

To get more insights on genetic testing, the impact of genetics on newer treatments, and what the future looks like for gene therapy, we asked neurologist, author, and Alzheimer’s expert Dr. Marwan Sabbagh to join us on Live Talks to discuss what is happening in the field.

Sabbagh, a board-certified behavioral neurologist at Barrow Neurological Institute’s Alzheimer’s and Memory Disorders Program and a professor at the institute’s department of neurology, has served as the lead investigator on a number of national clinical trials for Alzheimer’s prevention and treatments. In this conversation, he digs into topics including:

- the four things that can tell doctors if you’re progressing to dementia;

- the influence of certain genetic factors in your Alzheimer’s risk;

- the amount by which the ApoE4 gene increases a person’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s;

- the influence of certain genetic factors on whether or not it’s safe to take the new class of disease-modifying Alzheimer’s treatments (called monoclonal antibody drugs);

- how genes like ApoE4 are studied and what that could mean for people living with Alzheimer’s disease and those at risk of developing it.

Read or watch his conversation with Being Patient EIC Deborah Kan below.

Being Patient: Let’s start with talking about ApoE4, which is otherwise known as the Alzheimer’s gene. Tell us about what you know— whether you have one or two copies, what is that risk?

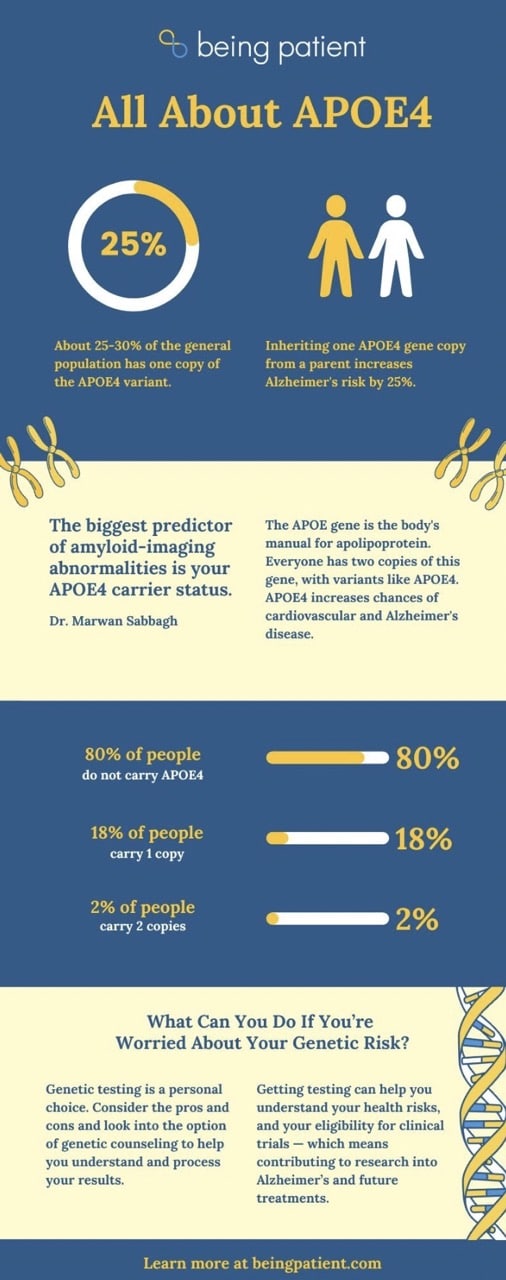

Marwan Sabbagh: Yes. It’s a very interesting story that started over 30 years ago. Most people do not realize that ApoE4 carrier status is actually originally linked to heart disease, not to Alzheimer’s disease. We got to this journey through the heart route, not the Alzheimer’s route. It was found out 30 years ago by Dr. Saunders, Corders, and Roses, and [at] Duke in North Carolina that, if you had two copies of the ApoE4 gene — one from each of your parents — you actually had a lifetime risk somewhere between 13 and 18 fold higher than the general population.

“It was found out […] that f you had two

copies of the ApoE4 gene —

one from each of your parents — you actually had

a lifetime risk somewhere between

13 and 18 fold higher than the general population.”

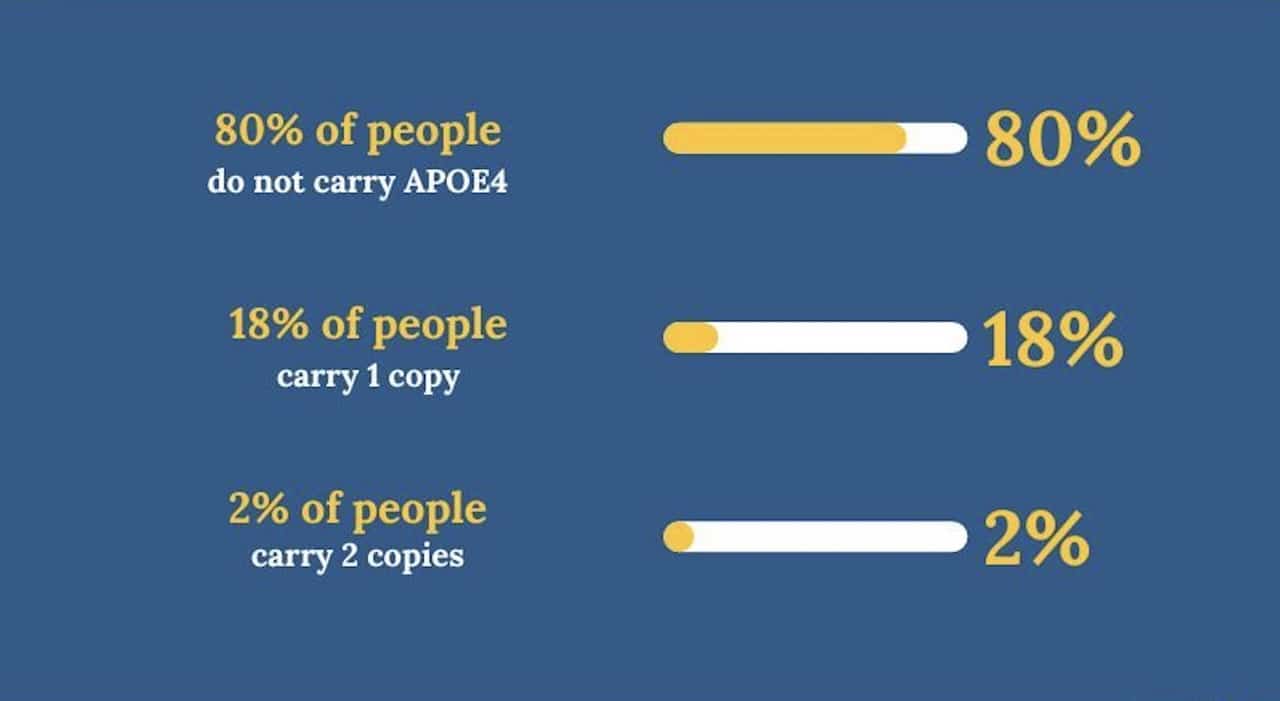

If you have a single copy, meaning one [ApoE4], you have a three to four times lifetime risk over the general population. When you break it down in terms of demography, 80 percent of people do not carry the ApoE4, 18 percent have one copy, and two percent have two copies.

Being Patient: We know with different ApoE genes, there’s a different level of risk. E4 is the risk, E3 is neutral, and E2, we believe, offers a bit of protection. Although, to this day, I’ve never met anyone with E2.

Sabbagh: I’ve met a few. I’m not sure it really applies in practice because each was very rare, as you just pointed out.

Being Patient: I always hear cholesterol transport mentioned when discussing these genes. Tell us a little bit about what we know about ApoE.

Sabbagh: A lot of things to say— number one is that when we eat food, we have proteins that carry things right out of our digestive system to our liver. Those are labeled lipoproteins. ApoE is responsible for carrying cholesterol and cholesterol-like molecules to the liver. We know that we have different types of Apo-like proteins. What we know about the like and that doesn’t have to do with Alzheimer’s. But what we know is that ApoE4 carriers tend to accumulate more amyloid in their brain or perhaps clear it out of their brain less efficiently.

A lot of people think that you’re just always making amyloid and clearing out amyloid and kind of turning it over constantly, but ApoE4 carriers do that [with] less efficiency. So, over time, ApoE4 carriers tend to have more amyloid in the brain. The question is, how does that link to the cholesterol transport mechanism? That’s still being explored. Because we always love the idea that ApoE be a druggable target unto itself, but nobody’s ever, as far as I know, have been able to achieve that.

“We got to this journey through

the heart route, not the Alzheimer’s route.”

Being Patient: I’ve also heard if you’re diagnosed with MCI, often the path to Alzheimer’s is faster for people who have ApoE4. Is that true?

Sabbagh: That is absolutely true. People with MCI or mild cognitive impairment means they have a cognitive disorder but are still independent. We know that there are four significant risk factors for progression to dementia: [the] presence of amyloid, significant neurodegeneration on your MRI, bottoming out on your neuropsych testings, and the ApoE4 carrier status.

So, if you are not an ApoE4 carrier, your risk of progression to dementia is six percent per year. If you’re an ApoE4 carrier, it’s 17 percent per year, so it is a significant predictor of future decline.

Being Patient: In layperson’s terms, what’s happening is the efficiency of cholesterol, or something goes wrong with the cholesterol transport to make the brain more susceptible to building up plaque. Is that right?

Sabbagh: That transport mechanism theory has been kicked around, but the truth is, we know the observation ApoE4 carriers have more amyloid; maybe they’re just not clearing out. But we’re not sure how the cholesterol transport mechanism ties so closely to amyloid production or clearance. I think that we have an association; we just haven’t figured out the connection quite as well as we should.

Being Patient: People always ask me where they should be looking in terms of what’s coming next in research, and I would say genetics because I think there’s a lot of research going on. A couple of years ago, you and I were talking about blood tests and diagnostics. Now, I feel like we’re moving onto genetics. I know that there’s gene modification, gene theory, and medications being tested to alter the risk that E4 has and make it act more like a non-risky, like E3 or E2. Tell me a little bit about what’s going on in the landscape of research and genetic modification.

Sabbagh: 10 years ago, we would have said that’s science fiction, but truth be told, it’s actually happening, as you just commented. There’s actually a company that I know of that’s proposing gene therapy that would genetically alter ApoE4 to not be working like ApoE4, so essentially, turning off ApoE4. That’s the first generation of actual real gene therapy. That’s now, I think, the clinical trials going on in that. I suspect we’re going to do more and more stuff like that as time goes on.

Being Patient: The other thing I need clarification on with genetics is that we still need more data on different races and populations. [Being Patient reported on one study of ApoE4 amongst the American Indian population in which researchers found this genetic variant isn’t a driver of Alzheimer’s risk for American Indians the way it is for the white population.] Tell me a little bit about what we know in terms of different people’s races and the risk profile with genetics.

Sabbagh: That’s been looked at all over the world, the association with age, gender, genetics, and family history. The idea is that you say the interaction between ApoE4 carrier status and risk is not as robust as it is in Caucasians in Western countries. That’s been looked at all over the world. I think we know that it’s just not as robust, but it’s not zero. It’s not like not having ApoE4 or having ApoE4 in any ethnic group is never a risk. It’s just less of a risk.

The whole thing about African Americans [for example] is that there are some thoughts that they have combined multiple risks. They tend to have more diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, and so it might not be strictly an ApoE4 risk — it’s a combined risk.

Being Patient: Where is the research getting interesting? Can we look at genetics in terms of prevention instead of a cure?

Sabbagh: You and I had this conversation, two, three, or five years ago, [that] the whole idea of ApoE genotyping was taboo. Like, “You shouldn’t do that, it’s dangerous.” So, one thing that I am happy [about] is that we’re discussing it, number one. Number two is that genetic testing is less taboo than it was. Mainly because in the last year and a half, there are now consensus guidelines saying if we’re going to give these new monoclonal antibodies, you must do genetic testing for risk stratification.

We went from not talking about it at all to now using it for risk stratification because we know that if you’re an ApoE4 double copy, your risk of having complications with the monoclonal [antibody treatments for Alzheimer’s] is quite high. What I’m saying is now, we’re all of a sudden discussing it.

“We went from not talking about [genetic testing]

at all to now using it for risk stratification

because we know that if you’re an ApoE4

double copy, your risk of having

complications with the monoclonal

[antibody treatments for Alzheimer’s] is quite high.”

The funny thing is that 23andme has been doing your ApoE genotyping for years without any genetic counseling. So, the whole taboo was always, I thought, a little bit on the arbitrary side, but I’m glad we’re discussing it. I’m glad that people are readying themselves to be tested.

Being Patient: How do you use it for diagnostics? You see a lot of patients. What percentage do you feel like are willing to have that genetic test?

Sabbagh: I will tell you more than people think. I am actually one of the few docs in America that has been doing ApoE genotyping for years. I explained it in advance. I never dropped blind and never tried to surprise them.

I say, “Here’s what I’m doing, and here’s why I’m doing it.” I’ve been using it in the proxy diagnostic modality. Beyond that, I will tell you that we’re now using it for risk stratification. So, if there’s any chance I’m giving a patient a monoclonal, I’m absolutely going to get their ApoE genotyping. We must think about it both from risk stratification and from proxy diagnostics.

Being Patient: Tell me a little bit about what it means to find people with ApoE4 for research overall; they’re a targeted risk population which science can learn a lot from. What primarily are we looking for? What is the value of researching this subgroup of the population?

Sabbagh: Yes. When I see a young person, and my definition of a young person is under 70— if I see a young person with progressive amnestic cognitive decline, one of the very first things I’m leaning toward doing is genetic testing early because they tend to be the homozygotes. The homozygotes tend to present in their 60s, heterozygotes in their 70s, and noncarriers in their 80s, roughly speaking.

We also know that homozygous [cases] tend to progress more rapidly. They have more pathology. They have more complications. Genotyping actually adds a lot of value to the conversation. So, I use the profile of the patient to determine whether I’m going to do genotyping.

Being Patient: What do you think people should know before they get genetic testing?

Sabbagh: We used to say genetic counseling. I think that is not necessarily the case. Without being self-promoting, I would tell them to buy my books because I’ve written a few books on the topic. That would be one thing. Beyond the self-promotion, I will tell you that you should get a deep dive [into] what it means to do ApoE.

“We also know that homozygous [cases]

tend to progress more rapidly.

They have more pathology.

They have more complications.”

Congress passed a law in 2008 called the Gene Act, the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act, which says you cannot lose your ability to get health care insurance on the basis of your genetics, but you can lose your ability to get long-term care insurance. So, we caution people who are not symptomatic to not get tested routinely.

READ MORE: The Pros & Cons

of Genetic Testing

When we’re talking about this conversation, I would never draw asymptomatic people. I only draw people who are coming to my clinic, who are having symptomatic complaints, etc. Just to give you that perspective, I would not do it for risk stratification. We have to be very tailored and selective in how we use these new tests.

Being Patient: Can you identify through the patients you see and in what you’ve done that people with homozygous E4 get plaques in their brain earlier than normal? Or does it just speed up the whole process?

Sabbagh: Yes, and yes, we know that. Kind of the rule of thumb from all the data is that if you’re accumulating pathology, your symptoms start 20 years after you start to accumulate pathology. If you’re an ApoE4 homozygous, meaning two copies, and you’re coming to my clinic at age 65, that means you’ve been accumulating pathology in your brain since [your] mid-40s. It’s very young. We need to re-engineer the whole concept of Alzheimer’s. We think of it as an elderly disease when, in fact, it is probably a middle-age or lifelong disease.

Being Patient: With these new monoclonal antibodies coming to market, what is the scenario for people with a genetic risk? I have had people within our community ask if they should be considering these drugs before they even know— if they have a gene, or if they have a big family component? Tell us a little bit about who gets to take the drugs and who doesn’t, and how they can be used as prevention today in terms of what we know because, obviously, they’re very new drugs that have come to market.

Sabbagh: The new drugs we’re talking about are called monoclonal antibodies. These are drugs that are engineered to remove amyloid out of your brain, and they do it very, very well. We have one now, lecanemab, already approved. We expect, within the next two to three months, donanemab to be approved. Everybody in my world says donanemab should just get approved, so I don’t think there’s an issue about that. These drugs work very well. That’s not the issue. The issue is risk.

“We need to re-engineer the whole concept

of Alzheimer’s. We think of it as an

elderly disease when, in fact, it is probably

a middle-age or lifelong disease.”

The issue is about risk stratification. So we know that one of the most common complications of these drugs is something called ARIA, amyloid-related imaging abnormality. The biggest predictor of ARIA is your ApoE4 carrier status.

Let’s take the new drug called Leqembi, or lecanemab: If you’re not an ApoE4 carrier, your risk of getting Aria is 5 percent, and if you’re heterozygous, meaning one copy, it’s 15 percent. If you’re a homozygous, it’s 33 percent. So, the ApoE4 carrier status is the determinant of the probability of developing these complications.

“The biggest predictor of ARIA

is your ApoE4 carrier status.”

I only do the genotyping nowadays, not only, but most commonly use the genotyping if I am selecting a patient for a monoclonal. So if I say to you, “Deborah, I’m going to put the patient on monoclonal,” then part of my diagnostic evaluation includes the ApoE4 genetic genotyping.

I have to tell you now that many people are already on these new treatments. I’m a little afraid to give the homozygous, two copies of E4, to give them these new treatments because of the risk being so high.

Being Patient: Do we know why they have a higher risk for ARIA?

Sabbagh: The prevailing thought at this moment is [about the] amyloid deposits in the blood vessels called cerebral amyloid angiopathy. ApoE4 carriers tend to have more cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Because you have more amyloid in your blood vessels, when you bind those blood vessels with these monoclonal antibodies, or at least the amyloid, you make them leaky. That’s what’s causing the ARIA.

Being Patient: Is there, in fact, a scenario where research could start treating before the presence of plaques?

Sabbagh: Excellent question and that is an area of hot debate in the scientific community. I think people think that these new treatments could be useful before the onset of symptoms when you’re starting to accumulate plaques. Those trials are actually ongoing right now as we speak. So, we expect to see those trials answer that very question that you just asked, with the idea that even before you’re having symptoms, if we determine you have amyloid, we’re already trying to take it out of your brain.

Being Patient: How is that possible? If you don’t have it, how do you take it out?

Sabbagh: Well, you would have just the beginning of accumulation; [that] is the idea of these new treatments: lecanemab, donanemab. But, what you’re asking is even more forward-thinking, and the idea is that we would one day potentially vaccinate against amyloid or vaccinate you in a way that blocks the effect of ApoE4. These are things that have been positive but never pursued, at least not yet.

Being Patient: What does that exactly mean? I know that there are about nine vaccines for Alzheimer’s under trials. How do you vaccinate for Alzheimer’s?

Sabbagh: The vaccine is for amyloid, and so what you’re stimulating [is] your immune system to create antibodies against amyloid. Instead of giving it as an IV, you’re making your own immune system do that. That’s what I think these drugs could do. We tried that 20, 22 years ago, and it did not end well and with a lot of complications.

That’s why this field has kind of been slow to come back to vaccinations because the problem of the vaccination is there’s no on-off switch. Once you turn the immune system on, you have no ability to turn it off. When they’re coming back in with vaccinations, the idea that your own immune system would find amyloid and remove it is really where the field would like to go. We tried before without success.

Being Patient: Isn’t some amyloid OK? Is it just when things go wrong, that’s when it becomes not okay anymore?

Sabbagh: A lot of some amyloid we expect as you age, but the question [is] the type of amyloid. Typically, as you age, you accumulate 40 amino acid amyloid, but it’s the Alzheimer’s [that] is the 42 amino acids. The type of amyloid is number one. Number two is that it reaches a point where the species of amyloid, the oligomeric species, starts to damage this brain environment, and that’s when you get the spread of tangles and tau. It’s not just the presence of amyloid, but the certain progression of the evolution of amyloid starts to damage the environment, the milieu, that causes the spread of the disease.

Being Patient: A lot of people are focused on plaque. In the past, a lot of the studies targeting removing beta-amyloid have failed historically in Alzheimer’s disease. Now, we’re seeing immunotherapies for Alzheimer’s. Those are the MAB drugs and monoclonal antibodies, where we employ our immune system to fight the plaque. Can genetics work in terms of digging into the research for other targets? We have yet to talk about tau or inflammation. Is there a relationship there that we should be thinking about in terms of genetics?

Sabbagh: People have looked into that possibility, but I’m not sure. I think there are things that people are looking at in the inflammatory path cascade, but tau is usually perceived as a marker of injury. Once your brain is injured, then you start to accumulate levels of tau. The concept is that you can target tau, but I don’t know about the genetics, specifically of tau, since that seems to be a marker of injury.

Being Patient: Are people with ApoE4 heterozygous, or just one copy, valuable to research studies?

Sabbagh: Very much. I mean, you understand that the majority of people with Alzheimer’s disease probably [have] one copy of the ApoE4. So, if you take the fact that 60 percent of people with Alzheimer’s disease carry at least one copy of the E4, maybe 20 percent [have] two copies of E4. So, you’re still talking about [how] most people with a single copy of E4 get Alzheimer’s, or I should say most people with Alzheimer’s have at least one copy of E4.

“Once your brain is injured, then

you start to accumulate levels of tau.”

We know that it’s much safer to give them monoclonal antibodies. I don’t think anybody would argue with that; if you have one copy, I think you can go ahead and give them monoclonals. But you know, people are starting to target the genetic subtypes for different treatments, and so I think we could see more and more like that.

Being Patient: What does it look like to take medication that makes a variant of our genes act differently? With gene therapy, you’re modifying the gene and then putting it back into our systems. How does that interact with our genetics? I know the environment can change our genetics with epigenetics, but what does that look like in the form of medication?

Sabbagh: Right, so this is still relatively newer. The earliest attempts that were done with gene therapy were things like cystic fibrosis, and they have made some progress there. Then, brain cancer, like glioblastoma, they’ve done that with gene therapy. So, we know that when you have extreme diseases, you go for extreme treatments. That is being positive and proposed to be done in Alzheimer’s. I’m not sure that we have a clearer way forward for that. I think it’s still early days there, and we need a lot more development there.

Being Patient: Tell me a little bit about the early onset markers. We’ve identified APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2. Those are conclusive genetic links to Alzheimer’s— early onset, for that matter. These are rarer genes—what’s happening with those people and research?

Sabbagh: Those are very, very rare. Of course, they’re famous because Columbia, South America, was the PSEN cohort, PSEN1. I will say to you that those are exquisitely rare in the general population. Those are people who have autosomal dominant, [which] means that everybody in their family, every generation, has had Alzheimer’s. They tend to get Alzheimer’s symptoms in their early 40s.

Actually, I’ve only had one in my practice ever, and PSEN2; similar but [in] early 50s. So, they’re not common, and we don’t routinely test them unless they’re coming in very young. The APP mutation is also relevant because that’s what we see with Down syndrome, people getting Alzheimer’s at a very young age in their 40s as well.

Being Patient : Someone commented, “My three adult children have a 50% chance of inheriting their father’s familial early onset dementia. He died at 51, as did his older sister and mother, with no signs of Alzheimer’s in his autopsy.” They’re asking if they should get genetically tested. To what end is the value of three family members all getting genetic testing?

Sabbagh: That’s a very emotional question. I’m sorry for that situation. The first thing I would tell you, [that is] the kind of person I would send to genetic counselors. I would not just routinely order it. PSEN testing is available through Athena Diagnostics and a couple of other companies, but it’s something you cannot unlearn. Before you decide to do that, you better sit down with a genetic counselor and think about what that means for your adult children. So yes, you can get tested; I [would] do genetic counseling first.

“PSEN testing is available through Athena Diagnostics and a couple of other companies, but it’s something you cannot unlearn.”

Being Patient: What are your thoughts about the blood tests in the direct-to-consumer market? Should people order a blood test and see what their risk profile is?

Sabbagh: The answer is myself, and other experts, are a little bit lukewarm about the idea of off-the-shelf testing. I have the blood tests in my clinic, and I ordered [them], but I will tell you that I do not advise people not to do this without having a full consultation. When I’m drawing these tests, Deborah, I’m doing it in the context of actually establishing a relationship with the patient. I would caution people about not routinely getting tested because then you have follow-up and then you have interpretation issues. It’s really difficult. Most doctors have no idea what it means; only a handful of the experts know what it means. So, I’m not a big fan of it.

Being Patient: One of our viewers asks about ALZ-801, which the FDA approves. The drug is from Alzheon, who is the sponsor of this talk. However, we have complete editorial control of this talk, and we’re not instructed what to say or what questions to ask. In terms of this new treatment, would it be prescribed to asymptomatic ApoE4 homozygous patients?

Sabbagh: Alzheon has a drug called ALZ-801 that is finishing their study called the Apollo study. The ALZ-801 study is in people with ApoE4 homozygotes specifically. So, this is not everybody. It’s only the people with the homozygous, meaning two copies of ApoE4, because their phase two trials showed very, very clearly that they had a very robust signal in ApoE4 for two copies of ApoE4.

The reason this is also important, from your perspective, Deborah, is that it’s an oral medication. It’s not an IV. It can be taken at home. You don’t need to go anywhere, and so people are excited about it because it could be a very good solution. The question is, what do I think that drug will work for? Homozygotes, I’m pretty sure it has a good shot on gold.

That said, the question is: will it be available or useful for everybody with Alzheimer’s? I’m not sure the data is there yet. What I will say is it probably is going to be a good choice for people with homozygotes, mainly because the risk of the monoclonals is also not very favorable. So, we need a new option for them anyway.

Being Patient: Do you think that if we do another talk on genetics, five or ten years down the road, there’s going to be a pill if you are a high risk that you’re just going to be able to take?

Sabbagh: What we do now, and what we do five years from now, as [you’re] astutely questioning is, it’s going to obviously change. I will tell you that these drugs are developed for people with symptomatic disease. What you’re asking me is, could they be used before the emergence of symptoms? And we just don’t know the answer to that.

Being Patient: It’s an area that research is pursuing.

Sabbagh: Absolutely. Particularly right now, with the monoclonal, I’m not sure either one is in a prevention trial yet. I’m pretty sure it’s not, but one could envision a prevention trial. Yes.

Being Patient: So, do you predict that we’ll be having a different conversation in five years?

Sabbagh: I do. I think because we’re going to be doing more and more people doing their genetic testing and trying to get prevention strategies in place before the emergence of symptoms.

Being Patient: How much of lifestyle can reduce impact for those genetically predisposed?

Sabbagh: Actually, one of my books is with Jamie Tyrone, and we wrote a book called Fighting for my Life, and she has ApoE4 homozygote, meaning two copies. She’s still asymptomatic. It’s become a very strong voice in our space. There is a huge interest in seeing if we can mitigate genetic risk through lifestyle interventions. [It is] actually a big area of research because a lot of people think that we should be trying to prevent our Alzheimer’s symptoms, not treat it once you have it, but try to prevent it to begin with.

So, there are now studies on diet and exercise specifically tailored to these genetic subgroups. I think that the answer is that you could move the needle. We don’t know how much, but I think you can move the needle with lifestyle-directed interventions.

Katy Koop is a writer and theater artist based in Raleigh, NC.