Mounting evidence shows that viruses lead to brain degeneration. So, scientists are trying a new approach to treating Alzheimer’s: antivirals.

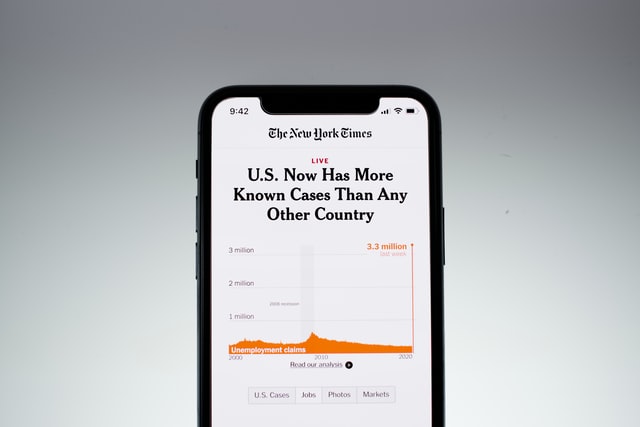

Infections — from herpes to flu to COVID to gingivitis-causing bacteria — have been linked in research, over and over, to at least six different brain diseases, Alzheimer’s included. In particular, the evidence linking COVID to cognitive impairment has reignited interest in funding these once-fringe ideas. The most recent study looked at more than 800,000 people linking severe viral infections like the flu to an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis over the ensuing 15 years.

The researchers tracking these links over the past several decades are celebrating an important stride forward: The first trial of an antiviral treatment for Alzheimer’s is now underway.

A new clinical trial called VALAD is underway to test whether an antiviral medication, valacyclovir, can halt the progression of mild Alzheimer’s. The study is testing the antiviral in people with mild Alzheimer’s and either Herpes Simplex Virus 1 and Virus 2.

It will be a few years before there is data to determine whether this approach is effective in treating Alzheimer’s, but in the meantime, Ruth Itzhaki, a professor from the University of Manchester who has studied the viral-Alzheimer’s link for more than three decades, says evidence is mounting in its favor.

Why Herpes? “It seems to be present in a high proportion of both elderly normal people and Alzheimer patients,” Itzhaki told Being Patient. When these viruses enter neuronal cells, their DNA is folded up and sequestered by the neuron to prevent an active infection. In this form, the Herpes virus can lay dormant in the brain for decades. “What we think is happening is there’s recurrent reactivation of the virus,” she said. Exposure to brain injury, other infections, or stress may be responsible for allowing the viruses to “wake up” and cause an active infection.

There’s plenty of evidence that other viruses may do something similar. In 2022, scientists showed that the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) — best known as the cause of mononucleosis (or “mono”) — is the leading cause of multiple sclerosis. The EBV belongs to a family of viruses linked to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

Meanwhile, HSV 1 and 2 belong to that same family of viruses.

The randomized double-blind trial is following 130 people. They receive a daily dose of placebo or the antiviral drug over the course of 78 weeks — a year and a half.

During that time, researchers will test whether people taking the antiviral experience slower cognitive decline than people on the placebo, and how the amyloid plaque in their brains — the best-known biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease — compares to people on the placebo.

The viral hypothesis of Alzheimer’s

According to the viral hypothesis of Alzheimer’s, viruses like Herpes may be responsible for kickstarting the disease process. Itzhaki explained that the viruses don’t always cause symptoms, but if they’re activated later in life it could spell trouble for the brain later in life. “Events such as stress, infection, or immunosuppression reactivate it causing damage to the brain,” Itzhaki said.

Triggered continuously, these reawakened viruses cause the damage to pile up. This damage could drive the development of Alzheimer’s disease. “Certain infections have been known to cause reactivation of viruses for a very long time,” Itzhaki added, bringing up recent evidence that COVID infections lead to reactivation of the chickenpox virus, causing shingles. COVID could cause many other viruses in the brain to “wake up contributing to long-term cognitive impairments.

Itzhaki and other researchers have validated this hypothesis in disease models.

A 2018 Taiwanese study looked at data from thousands of electronic health records. People diagnosed with HSV infection were more than 2.5 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s or other dementias 10 years later. They also found that taking antiviral drugs reduced that risk. But, the people considered as controls could have had an asymptomatic HSV infection.

In 2020, another study controlled for this limitation. They followed carriers of HSV-1, controlling for other demographic factors as well. They found that antiviral treatments reduced the risk of Alzheimer’s.

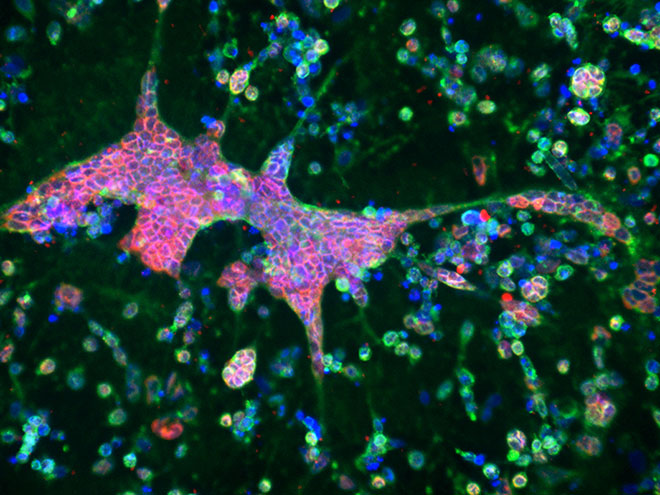

That same year, another group of scientists grew a brain organoid — a “mini” model brain made out from stem cells — and infected it with HSV-1. Their model showed characteristic features of Alzheimer’s — spontaneous cell death, inflammation, amyloid plaques, and glial activation.

Itzhaki says she received pushback from other researchers in the field who have focused exclusively on amyloid.

“They’ve been working on the field so long that they don’t want to get amyloid pushed out of the picture,” she said. “They don’t read the papers and say there’s no evidence [for the role of viruses in Alzheimer’s], which is ridiculous.”

Itzhaki emphasized that viruses may be just one potential cause of the disease. “I think that it’s quite obvious that there’s diseases multifactorial,” she said. “I’m not for a moment saying that it’s a virus that causes I’m saying if we think the evidence is a cause, not the cause.”

Preventing HSV from “waking up” or activating could be a neglected part of the Alzheimer’s puzzle, she said. Even if the trial doesn’t go as planned, it doesn’t mean the end for the viral hypothesis. It took three decades of research and dozens of failed drugs for scientists to bring Leqembi to market — the first drug that shows removing amyloid plaques could improve cognitive function.

Davangere P. Devanand, the director of geriatric psychiatry at the Columbia University Medical Center who is running the VALAD trial, told Being Patient that the trial will end in December 2024, with results becoming available in 2025.