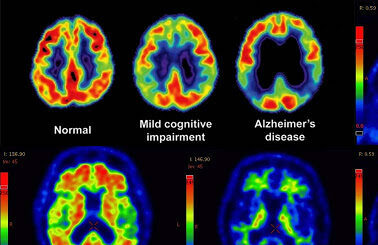

New research shows that people living with anxiety, depression and other neuropsychiatric conditions tend to develop symptomatic Alzheimer’s as much as seven years sooner than people without these conditions.

“There is no health without mental health,” developmental psychologist Dr. Darya Gaysina told Being Patient in an interview in 2018. Research has shown that depression and anxiety are each linked to Alzheimer’s and other dementias, particularly in older adults. Now, a new study makes this link less abstract, providing insight into just how quickly neuropsychiatric conditions appear to age the brain.

The study, which will be presented at this year’s American Academy of Neurology annual meeting in April, found that among people who do develop Alzheimer’s disease in their lifetimes, those with depression may start to experience the symptoms of dementia about two years earlier than those without it. Anxiety can speed the onset of dementia symptoms by three years. For people with both, Alzheimer’s may arrive even sooner.

The “why” is still unknown, but authors of the study including Dr. Zachary A. Miller, of the University of California, San Francisco are parsing the complex relationships between neuropsychiatric disorders, neuroinflammation and dementia, looking for cause and effect. Their recent data has yielded some new theories.

“We hypothesize that the presentation of depression in some people could possibly reflect a greater burden of neuroinflammation,” Dr. Miller said in a news release, explaining that study participants with depression were more likely to also have an autoimmune disease, and those with anxiety were more likely to have a history of seizures. Both of these are linked to neuroinflammation, which is in turn under increased scrutiny for its role in the development of Alzheimer’s.

Researchers found that people with both depression and anxiety were more likely to be female, which in itself is an emerging Alzheimer’s risk factor. Otherwise, the study reports, they did not widely share additional Alzheimer’s risk factors.

Past researchers have looked at brain volume loss as an explanation for the link between Alzheimer’s and anxiety, but Dr. Miller’s team theorizes that the presence of anxiety might indicate a greater degree of “neuronal hyperexcitability,” wherein the brain’s networks are overstimulated. Knowing whether or not this triggers Alzheimer’s onset, he said, could guide researchers toward new drug targets for dementia prevention.

“Certainly this isn’t to say that people with depression and anxiety will necessarily develop Alzheimer’s disease,” he said, “but people with these conditions might consider discussing ways to promote long-term brain health with their health care providers.”

Beyond the most common neuropsychiatric disorders, depression and anxiety, Dr. Miller and colleagues screened participants in search of a history of similar conditions that could share this neuronal hyperexcitability affect, such as bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and schizophrenia.

Of the 1,500 people with Alzheimer’s in Miller and colleagues’ study, 43 percent had a history of depression, 32 percent had anxiety, 1.2 percent had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, 1 percent with PTSD and 0.4 percent with schizophrenia. Another finding was that while the individual disorders themselves may appear to be correlated with some degree of heightened risk, the number of neuropsychiatric conditions played a major role: The age of onset grew twice as young with each psychiatric disorder diagnosis added.

People with only one disorder developed symptoms about one and a half years before those without any diagnosed psychiatric disorders. Those with two psychiatric conditions developed symptoms 3.3 years earlier than those with none. Three or more psychiatric disorders was correlated to the appearance of symptoms a little more than seven years earlier than people with no such conditions.

These findings will add to existing evidence of a link between various neuropsychiatric conditions and higher risk of Alzheimer’s onset during one’s lifetime, and more specifically earlier onset. One past study found that older adults with depression are more likely to experience memory problems, while another indicated that older adults with depression have a 65-percent-higher risk of Alzheimer’s. A study published in October 2020 found that PTSD has increased dementia risk over risk to people without PTSD by 61 percent. A 2015 study found that participants with bipolar disorder had an 87-percent-increased risk of developing dementia compared with those with major depression. There is also precedent for a schitzophrenia-dementia link; research has found that people with schizophrenia had a greater risk not only for developing dementia but also earlier appearance of symptoms. More than a fifth of the individuals with schizophrenia who went on to develop dementia in one study were diagnosed with dementia before 65, compared to a fifteenth of individuals without schizophrenia who experienced early-onset dementia.

This study is different in that it looks across all of them and compares age of onset to those without neuropsychiatric diagnoses. One limitation cited by the researchers is that the data came from a tertiary specialty memory care center and retrospective chart review.

According to Dr. Miller, to understand the true impact of psychiatric disorders like depression and anxiety on the appearance of Alzheimers, more research is needed. He hopes, he said, that such learnings could improve researchers’ understanding of “whether treatment and management of depression and anxiety could help prevent or delay the onset of dementia for people who are susceptible to it.”

The study will be presented virtually at the American Academy of Neurology’s 73rd Annual Meeting, April 17 to 22.