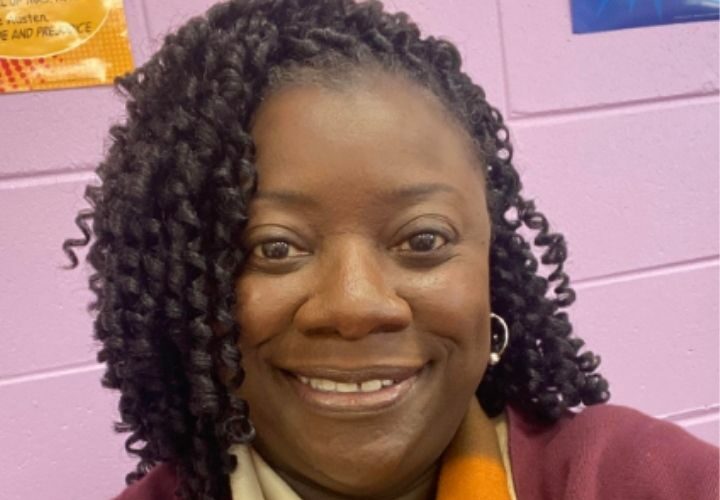

Alzheimer’s advocate GeVonna Fassett spent more than a decade caring for her late mother. Today, her organization, Olivia’s Prayer, supports dementia caregivers and raises awareness in Chicago’s Black community.

This article is part of the series Diversity & Dementia, produced by Being Patient with support provided by Eisai.

Caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s is not an easy journey, but 62-year-old GeVonna Fassett views it as the most important job she’s had in her life. Fassett said she relished the chance to care for her mother for nearly 12 years until her death at age 91 in November 2020. “It might have been hard, but I am so blessed,” she said.

The Chicago native is the founder of Olivia’s Prayer, an effort — named after her mother — to raise awareness about Alzheimer’s in the Black community and offer much-needed support to its caregivers, who can struggle with issues such as finances, lack of resources and even stigma.

Fassett moved back home in 2009, after the death of her father, so she could care for her mother, who’d been diagnosed a few years prior. “My mother was a good mother, so I didn’t think twice about it,” she said.

Early on, Fassett, whose background is in broadcasting, started volunteering for the Alzheimer’s Association. Still, she saw a stark need for greater advocacy and resources for Alzheimer’s caregivers within the Black community, she said, and in late 2014, she launched Olivia’s Prayer to help address that need.

A key component of her message is that caregivers must take time to care for themselves, Fassett told Being Patient: “If you have a poor caregiver, a drained caregiver, often you’re going to have a neglected patient. If you take care of yourself, you have more to give.”

Olivia’s Prayer conducts caregiver and awareness programs in partnership with Chicago area hospitals and organizations. Its main partner is Chicago Commons, a nonprofit that offers day services and home care programs for older adults, mostly from the Black community. Fassett’s mother had been among them.

DeLizza Russell, senior director of adult day service at Chicago Commons, called the partnership with Fassett “a great marriage.”

“It’s the importance of not just educating caregivers, but also giving them a safe place to express themselves in a ‘no-judgment’ zone,” she said.

According to Russell, there aren’t enough adult day care programs, particularly within the Black community, and when there are openings, families often don’t know to take advantage of them.

“I always become shocked when I am doing an intake and I hear, ‘We didn’t know anything about adult day service,’” she said.

Another obstacle Olivia’s Prayer works to address is the stigma and shame people living with Alzheimer’s and their families may face, Fassett said. For example, she said, she knows of a Black church in Chicago whose leadership concealed from the public that its minister had the disease, choosing instead to quietly remove them from their post.

Rather than hide Alzheimer’s, the Black community needs to be encouraged to have open discussions about the disease, which would prompt caregivers to open up, she said.

“Don’t be afraid to ask for help,” she said. “And love on them [relatives with Alzheimer’s]. That’s the best we can do. That heals.”

Fassett and Russell both noted that the financial challenges Black families face also play a role. Data shows the median Black household has a net worth equal to 1/10 of the median white household.

Generally, the Black community pays into long-term care insurance at lower rates than other groups, and many families don’t have the private means to pay for adult day services, Russell said. People can be eligible for state financial assistance, but some relatives are reluctant to disclose a lot of private information, she added.

Black families are more likely to keep their older loved ones living at home, so the availability of adult day service is crucial, Fassett and Russell said. More help is needed on weekends and even 24 hours a day, particularly for caregivers who work second or third shift, they said.

Fassett said that, in the years she cared for her mother, she relied on property investment proceeds, then started receiving a monthly allowance from her mother’s estate. She also became a certified raw food instructor — she calls it “my reinvention” — and taught classes from home.

Black Americans are twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s compared to non-hispanic whites. However, racial discrimination affects the way intelligence and cognitive function is assessed in Black individuals, who are also underrepresented in Alzheimer’s clinical trials.

To help address this disparity, Fassett said clinical studies recruiters should do more outreach in Black communities, such as showing up at health and senior fairs, and connecting with clinics and doctor’s offices.

“Wherever you’re going to have a population of seniors, that’s where you need to be,” she said, adding she has volunteered to participate in studies but was never selected.

A lot of Black Americans have trust issues, which can lead them to steer clear of participating in studies, Russell added.

Some people in the Black community can be in denial, attributing Alzheimer’s and dementia symptoms to normal aging, Russell and Fassett said. Because of that, Black individuals are less likely to be diagnosed, or get diagnosed after the disease has progressed into later stages, Russell said.

“People would say, ‘Oh, he’s just senile,’ like it’s something normal,” Russell said.

“Some people call it ‘Old-heimer’s,” Fassett said. “But at 60 or 70, if you see something wrong, acknowledge it. Pay attention.”

There has been increased awareness in the last couple of decades about the benefits of seeking an early diagnosis, “but we have a long way to go,” Russell said.

Inspired by what she learned from caring for her mother, Fassett is preparing to start law school in the fall and specialize in elder law.

She is also the author of the upcoming book, “Life AFTER Caregiving: Why Wait? Start Now,” which will be available in October 2022.

“I want to bring honor to caregiving,” Fassett said. “I always say there are four kinds of people: people who are caregivers, people who were caregivers, people who are going to be caregivers, and people who are going to need caregivers.”