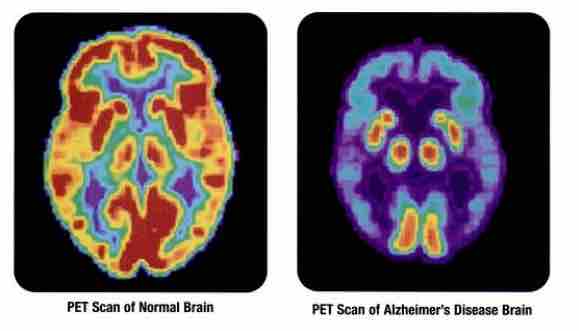

Structurally, men's and women’s brains are incredibly similar. So, why are so many more women living with Alzheimer’s disease? Chicago Medical School neuroscientist Lise Eliot explains what we currently know about gender and the brain.

Two thirds of people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s are women. Research shows that the Alzheimer’s biomarker tau protein accumulates differently and more quickly in women’s brains.

So, what is it that makes women more susceptible to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s? Researchers like Dr. Lise Eliot at Rosalind Franklin University are investigating the differences in brain structure for men and women. A professor of neuroscience, her research centers on brain and gender development.

Eliot joins Being Patient founder Deborah Kan to discuss the differences in brain structure between the sexes, and what future research could reveal about the impact of gender on the brain. Read or watch the full live talk below:

Being Patient: What do we know about how the structure of the brain in men and women differ?

Lise Eliot: Well, that’s a good question, and I’m happy to say we have plenty of data to answer that. Since brain imaging was born in the 90s, neuroscientists, not surprisingly, [have] been very, very curious about that question. I approached it when I was writing my book, Pink Brain Blue Brain, and since then, I have really dug into the literature and published a few meta-analyses and syntheses on this topic.

Here’s what we know for sure: men have larger brains than women. It’s about 11 percent larger on average. But of course, men are bigger than women; they’re usually about 18 percent heavier and nine percent taller. Nobody really thinks that that is meaningful in terms of either cognition or brain health.

Being Patient: So, in this case, size doesn’t matter?

Eliot: We do see a weak correlation between cognitive measures and brain size. But you really can’t compare intelligence across the average man and average woman and say, “Therefore, men are 11 percent smarter.”

In fact there’s no difference in IQ scores. It depends on what you measure and how you construct the test to see who’s going to come out smarter. There are average differences in cognition — women tend to be stronger in verbal skills and men in spatial skills, but those differences are pretty small. There’s quite a lot of overlap; you could never predict for any man or woman how strong they are in either of those areas.

“Here’s what we know for sure:

Men have larger brains than women.”

What I’m interested in is how those differences emerge because just because we see this reliable difference in 20, 30, and 60-year-old men and women doesn’t mean we were born that way. Of course, the experiences of being a girl and a boy are very different, a man and a woman. So, by the time we measure people in adulthood, you’re going to be looking at the cumulative impact of a lot of experience. That goes for the brain as well.

Being Patient: What’s the difference between gray and white matter in the brain?

Eliot: The gray matter are the cells of the brain, the neurons, as well as the dendrites, that are like the branches that receive [these] massive connections from other neurons. The brain is a huge network, so all of that connectivity is happening in the gray matter, but every neuron also has a big wire attached to it known as the axon.

The axons are actually the white matter because they are wrapped in something called myelin. That is a very dense fatty insulator, just like the insulator on your power cable that prevents current from leaking out, [so] you don’t get a shock when you touch your power cable. That’s what myelin does for our brains.

“Interestingly, larger brains tend to have

proportionally more white matter than

smaller brains because they have longer

distances to travel, just like a

highway needs to be wider.”

It’s really important for fast and reliable transmission from one part of the brain, one gray matter structure, to another. Interestingly, larger brains tend to have proportionally more white matter than smaller brains because they have longer distances to travel, just like a highway needs to be wider. The distance from [the] city to [the] suburbs is longer, so they’ll have a wider highway. That’s true for white matter as well.

Being Patient: How much do we have control over the size and health of our brains? How do we distinguish nature from nurture in terms of brain health?

Eliot: Assuming one doesn’t have an inborn genetic or hormonal deficit, I believe that most of what we do with our brain is a function of our experience, learning, health, environment, and so on. I just look at how every healthy child learns language effortlessly. Without any problem, they become quite fluent by the age of three without anybody teaching them.

Our brains are learning machines — they are ready to absorb. I think that most of the differences in our skills and our reactions are a function of our lifetime experience. You don’t read, write, or do math problems without a lot of experience.

Being Patient: Bringing it back to the gender differences, are male and female brains wired differently?

Eliot: Not much. One long-standing, I call it rumor, in the scientific literature was that women had larger hippocampi than men, proportionally. Whenever you’re comparing the size of a brain structure from one person to another, you always have to control for their overall brain size, because we have huge variations in population. Women were thought to have proportionately larger hippocampi, but that turned out to be about a one percent difference and not even statistically significant.

“Our brains are learning machines —

they are ready to absorb.”

Similarly, men were said to have a larger amygdala, which is the emotion center of the brain, which also plays a role in face recognition [and] aggression. You can take your pick what stereotype you want to associate with that claim. The truth is that men’s amygdala is maybe one percent larger than women on average.

The actual structures don’t differ in size between men and women, which is different from some other animals like birds where you have dramatic differences between the peacock and the peahen, or songbirds, where the male sings and the female does not, and you see specific structures that are larger in males and females. We don’t have that. I’ve described the human brain as sexually monomorphic. I teach medical students brain anatomy. When we take a donor brain out of formaldehyde, you have no idea whether it came from a man or a woman. Structurally, there’s almost no difference.

Functionally, there are claims for sex differences in functional networks. I have to say they have not been very well replicated across large studies. That may be because there’s so much variation in humans, or our methods aren’t quite as good as we thought they were for measuring functional connectivity.

“When we take a donor brain out of

formaldehyde, you have no idea whether

it came from a man or a woman. Structurally,

there’s almost no difference.”

There is this one network you may have heard of called the “default mode” network, which is our kind of idle brain when you’re not really doing anything. … That seems to be more active in women than men across many studies, but we don’t know what that means. Some have speculated that it makes women more vigilant, but it really is all speculation at this time. If you look at the specific networks that do something like language, there really is no difference. We use the same brain areas [and] the same connections to speak, hear, and listen.

Being Patient: Do we know why women are more susceptible to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease? It was originally thought this was because women live longer, but they’ve proven that wrong.

Eliot: I have to interrupt you there because that is not true. The largest epidemiological studies find that the reason more women are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s than men is a function of age and longevity. Women live longer, as we all know, and the risk of Alzheimer’s does not rise linearly with age; it goes up quite exponentially. You have more women than men in this very highest risk factor category. There is no difference in the incidence or prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease between men and women; it is all a function of longevity.

Being Patient: It’s interesting that you say that because that’s different from what many scientists believe, right?

Eliot: I think they do that because there is a lot of grant money out there to focus on women’s brains. There are a lot of pharmaceutical companies that want to address women’s brain health because, yes, twice as many women do live with Alzheimer’s than men. It’s a very real, clinical problem, but it doesn’t mean that our brains are innately different or that women are more predisposed.

“There are so many risk factors associated

with dementia that may differ

between men and women.”

The other thing is there are so many risk factors associated with dementia that may differ between men and women. That is depending on what cohort you look at because, for example, in the oldest generation, men were more educated than women were. That’s going to be contributing because we know education provides cognitive reserve [and] synaptic reserve to prevent Alzheimer’s. As we look at younger and younger cohorts, women are more equally educated or, in the youngest, sometimes more highly educated on average, and you’re starting to see some of those ratios differ. Gender ratios come down.

Being Patient: What do we know about how hormones affect the brain? As it’s been explained to me by other researchers, as women go through menopause, their estrogen drops in different levels of severity, and then their brains become more susceptible to something going wrong. What do you have to say with those hypotheses?

Eliot: I would say that correlation doesn’t equal causation. Yes, women undergo a decline in estrogen, rapid decline, and men undergo a slower decline in estrogen and testosterone. Remember, we all have estrogen and testosterone. First of all, from the brain side — I’m a neuroscientist, and that’s what I focus on — I’ve been looking long and hard to find a convincing effect of estrogen changes on brain structures and networks.

There are a lot of studies out there, but again, they don’t seem to be particularly consistent, and there’s a lot of [effects] just on estrogen that will affect blood flow. That’s thought to be kind of an artifact contaminating those studies. We do know that women who have a difficult menopause transition, who have a lot of hot flashes, and [who are] not sleeping well, can undergo a kind of a brain fog [and have] memory difficulties. That’s not all women; that’s maybe, at most, a third of women, so there’s tremendous variation.

Yet we all, if we live long enough, will go through menopause. I’d also like to point out that women live longer than men, probably for a reason. Anthropologists have developed this grandmother hypothesis that women may have been selected to live longer past our own reproductive age because we provide support for the grandchildren’s survival.

It would have been a pretty crazy brain selection mechanism that would allow women to live longer and yet to decline faster cognitively than men if we really need to keep our wits about us to gather calories for the grandkids.

Being Patient: Do we know the impact of hormones on the brain? As we age, we all decrease in testosterone and estrogen. Women have much more estrogen than men, so is there any significance? Do hormones need to be researched more?

Eliot: I don’t think it’s nearly as significant as most people believe. I also think it’s not correct that women have more estrogen than men because testosterone is converted to estrogen. Most of its actions are actually via estrogen, or many of its actions are in the brain. So, I think if you measure brain levels of estrogen between men and women, I don’t believe there’s much difference.

“To me, the most convincing evidence comes

at the menopause transition and into

perimenopause, when you have these

massive fluctuations and, ultimately,

a pretty steep decline.”

To me, the most convincing evidence comes at the menopause transition and into perimenopause, when you have these massive fluctuations and, ultimately, a pretty steep decline. That, of course, is what is triggering the symptoms of menopause. That’s where you see the biggest and only significant effects on cognition on things like verbal memory. Once women get past that, the decline is no different. The overall decline is no different between men and women, but they can have this fluctuating and very distressing period.

Being Patient: Do we know if those fluctuations have any significant longer-term impact?

Eliot: That’s a good question. I don’t think that’s really been explored that well. … That’s not really my field. I don’t really work on hormones, per se, but it’s possible. Again, this is a minority of women. We really do not understand why some women have more dramatic hot flashes [and] menopause symptoms than others.

Being Patient: Should we be studying gender differences in the brain? Is it significant to disease prevention?

Eliot: We absolutely should be studying gender differences, but everything we’re talking about so far has been sex differences, right? We take a thousand men and a thousand women; we scan their brains, we compare their brains. So, the differences there are pretty subtle, but gender is a whole different story.

Gender expression is not binary; it’s a mosaic within men [and] within women. I’ve been advocating that rather than using sex as our independent variable, we should use gender as our independent variable. So, in other words, score people on measures of masculinity and femininity, expressivity versus agency, and that may give us some more clues linking brain structure to function as well as some of these neural behavioral health risks.

“Gender expression is not binary; it’s a

mosaic within men and within women.”

Being Patient: What exactly is your research covering today?

Eliot: I’m still very much focused on trying to synthesize the massive, massive literature on brain sex differences. I’m fortunate that I don’t have any skin in the game. I don’t have a research grant to look specifically at the effects of estrogen on sex differences, so I tried to take [the role of] a neutral observer.

I’m still mostly focused on early development. In fact, we just did a synthesis with my team on fetal brain sex differences. Now, a certain number of women are getting MRI scans before birth and while pregnant. We have several dozen studies that have compared male and female fetal brains.

“I’m still very much focused on

trying to synthesize the massive,

massive literature on brain sex differences.”

Again, the only significant difference is male fetuses have larger brains than females. Toward the end of gestation, we start seeing them diverge, but again, male baby newborns are about half a pound bigger than girls. We just don’t know the significance of that. I’d also like to point out that all the other internal organs are larger in boys and men than women: the heart, the kidney, and the liver. We don’t ever talk about that and decide who has the better lungs and kidneys.

Being Patient: Are you looking at the physical differences in the structure to determine what that means?

Eliot: In early childhood, it’s particularly important because we do know that boys and girls have different risks early on. We know boys are [more] likely to be diagnosed with autism disorder. Actually, many of the neurodevelopmental disorders are more prevalent in boys, and a lot of the speech and language difficulties.

Whereas later, girls and women are more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety and depression. So, I’m interested in early brain development to see if there are structural and functional reasons to suspect male vulnerability.

We know boys are more vulnerable in other sorts of physical health, too; even Sudden Infant Death Syndrome is more common with boys than girls. Something about male vulnerability may be due to the fact that they have only one X chromosome whereas females have two.

Being Patient: Do you think research in early childhood development and identifying what the differences are will open the door to more studies about whether there are different vulnerabilities in the brain for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s?

Eliot: My view is that we need to focus more on the lifestyle and preventative factors that we know about. I mean, yes, there are genetic predispositions for Alzheimer’s. Fortunately, those genes are rather rare.

Physical exercise, social connectedness, and cognitive challenge — those are the things that are going to help buffer all of us against neurodegenerative disease, with physical exercise being the most important. Of course, men are generally more physically active than women, so that’s probably another factor contributing to some of these gender differences.

Katy Koop is a writer and theater artist based in Raleigh, NC.