How does Alzheimer's affect the brain? Here’s a look at what parts of the brain Alzheimer's affects and how the disease progresses.

Lapses in memory are a fairly normal part of healthy aging. But in the early stages of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s dementia, cognitive changes may be the result of Alzheimer’s pathology beginning to move through the brain. So, what parts of the brain does Alzheimer’s affect, how do those affects manifest in symptoms, and when in the progression of the disease do these symptoms show up?

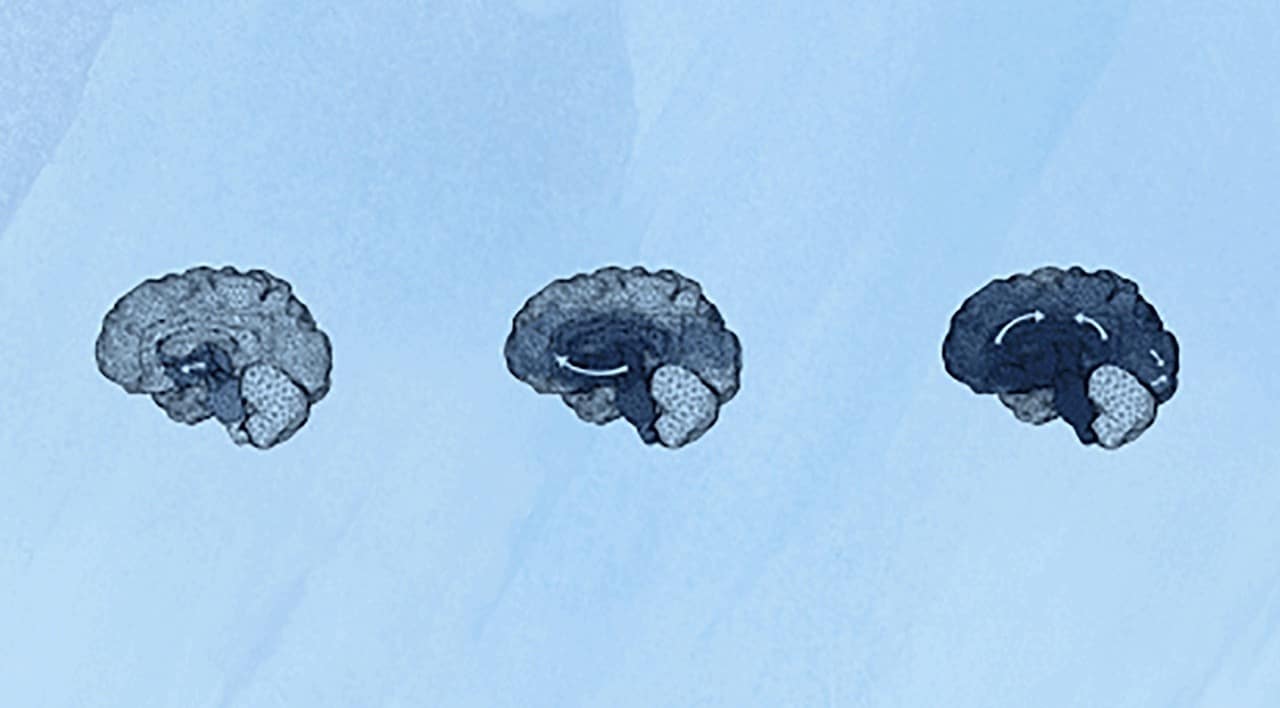

Alzheimer’s progresses in stages, As it moves through different regions of the brain, proteins — tau and beta-amyloid — tangle and clump, getting in the way of neurons, causing inflammation, and eventually, bringing about neuron death. With each new region of the brain affected, different symptoms appear: memory loss, changes in personality, apathy, and difficulty with everyday tasks.

Eventually, these symptoms progress to dementia. Here, it becomes difficult for a person to do everyday activities without the help of a caregiver. Tracking the course of the symptoms has given scientists a good idea of which parts of the brain are affected in what order.

How does Alzheimer’s affect the brain? Alzheimer’s disease pathology and plaques

If you want to know how Alzheimer’s affects the brain in terms of physical pathology, you have to look through a microscope: On the cellular level, there are specific changes that brains developing Alzheimer’s disease have in common.

While small forms of the beta-amyloid protein normally provide protection, they can aggregate into more toxic forms that lead to beta-amyloid plaques that form between neurons. Some smaller forms of beta-amyloid can be detected in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid, providing a diagnostic biomarker that can alert people that they may be at risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia.

Toxic beta-amyloid proteins can trigger a cascade of other cellular changes that precede Alzheimer’s and dementia. Inside of neurons, proteins called tau that help stabilize the cell’s skeleton also get tangled up. These neurofibrillary tau tangles disrupt the internal delivery systems of the neurons, leading to further dysfunction and cell death.

As neurons become damaged or dysfunctional, they activate immune cells within the brain — microglia and astrocytes — which can unintentionally lead to even more damage to different regions within the brain. These changes may occur earlier in some parts of the brain than others.

Along with the spread of amyloid, tau, and cell death throughout the brain, many important structures shrink significantly.

What part of the brain does Alzheimer’s affect first?

Alzheimer’s begins in the hippocampus and temporal lobes. The hippocampus is a seahorse-shaped region of the brain that, along with the nearby temporal lobes, plays a critical role in short-term memory, long-term memory, learning, emotional processing, and navigation.

Early Alzheimer’s symptoms like forgetfulness, issues with short-term memory, and difficulties with concentration, are linked to problems with these brain regions. These changes can be detected through cognitive testing to help determine if a person has mild cognitive impairment.

But by the time Alzheimer’s is diagnosed, the hippocampus displays the characteristic pathology of the disease: Neuronal cell death, neuroinflammation, beta-amyloid plaques, and tau tangles. With new brain imaging tools and blood tests, researchers are hoping to spot these signs of Alzheimer’s disease risk earlier and intervene. It is still unclear, however, whether clearing beta-amyloid or tau tangles before these symptoms appear could prevent or slow the onset of Alzheimer’s.

How does Alzheimer’s progress through the brain?

The amygdala and limbic system of the brain are also affected early on. The amygdala and other structures within the limbic system help regulate emotions and also link different emotions to our memories. It is usually affected after the hippocampus.

Normally, emotional cues can enhance our memory recall. But a person living with Alzheimer’s will not experience this boost in memory recall because of damage in the amygdala — an inflammatory cascade involving amyloid and tau buildup. Intriguingly, music can still help people in the later stages of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia recall important memories.

Additionally, when this region of the brain is affected, people may experience symptoms like depression, anxiety, apathy, and irritation, accompanied by cognitive impairment, like memory problems. More than 60 percent of people with dementia are also diagnosed with depression, which can cause the brain to age faster.

There is overlap between the pathology of depression and dementia, leading scientists to test whether depression drugs can treat cognitive impairment. A recent analysis found that the antidepressant drug fluoxetine shows promise in improving cognitive symptoms in Alzheimer’s.

What part of the brain does Alzheimer’s affect last?

The prefrontal lobe and cerebral cortex are affected in later stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The prefrontal cortex is involved in high-level reasoning and executive function, while other regions of the cerebral cortex are involved in language processing and social behavior. So, as Alzheimer’s disease progresses through these brain regions, people living with Alzheimer’s gradually lose the ability to perform complex tasks, and eventually, they may experience personality changes.

Pathological changes in the cortical regions of the brain can also contribute to other psychiatric symptoms of Alzheimer’s including anxiety and depression.

In the later stages, the disease can spread to the motor cortex making it more difficult to move around without the help of a caregiver.

Scientists are developing new ways to track the progression of Alzheimer’s through the brain

Researchers are constantly working to better understand neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, how it works and how it progresses — with the hope of learning how to stop it. In 2018, scientists from Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute and Stanford Bio-X developed a computer simulation to visualize how clumps of protein spread through the brain over periods of as many as 30 years.

“The real challenge is that cell death from toxic proteins occurs years, if not decades, before the first symptoms begin to show,” Stanford mechanical engineer Ellen Kuhl wrote at the time. “We hope the ability to model neurodegenerative disorders will inspire better diagnostic tests and, ultimately, treatments to slow down their effects,” she said.