The next generation of Alzheimer’s drugs help rejuvenate the brain’s immune system to fight against the disease.

The brain’s immune system is like an orchestra. Imagine the microglia are the violinists and cellists, the astrocytes are the brass section, and various other immune cells are the woodwinds. The players have spent decades honing their skills: When they’re playing in harmony, the brain is protected from infection and disease. But as they age, some of the players begin to slow down.

Alzheimer’s disease creates a whole lot of background noise in this mental theater — and it can throw the immune cells off their rhythm. A new generation of experimental Alzheimer’s drugs is now being developed to act as a conductor, helping immune cells harmonize and protect the brain.

Dr. Tommaso Croese, a neurologist and the medical director of the drug company ImmunoBrain Checkpoint, believes that leveraging the body and brain’s immune system is critical for treating Alzheimer’s.

Alzheimer’s drug Leqembi earned full FDA approval last year. But, while it is designed to clear up noisy beta-amyloid protein plaques that interfere with and damage brain cells, it doesn’t stimulate or train the brain’s immune cells to take care of the amyloid plaques — and it doesn’t address other brain inflammation or damage from Alzheimer’s.

“We are trying to exploit and harness our immune cells to counteract the pathogenic process that is ongoing in the brains of patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease,” Croese told Being Patient.

There are several drugs underway now by different drugmakers that take this approach.

Getting the immune cells back up to speed: turning up the T-cells

The body’s T-cells, an important part of the immune system, normally help the brain root out infections and disease. But as we age, they slow down and become less potent.

According to Croese, getting these T-cells back up to speed could help treat Alzheimer’s.

ImmunoBrain Checkpoint is trying to do just that. Croese and his colleagues at ImmunoBrain Checkpoint are testing whether an approach that’s proven successful for stimulating T-cells in cancer could also help people with Alzheimer’s. These cancer treatments help the T-cells find and destroy cancerous cells hiding out in the body — perhaps they can also help the T-cells hunt down diseased brain cells in Alzheimer’s.

“We are trying to exploit and harness our immune cells to counteract the pathogenic process that is ongoing in the brains of patients affected by Alzheimer’s disease,” he told Being Patient.

According to Croese, these T-cells play an essential role in the brain, and similar approaches could help treat various neurodegenerative diseases.

“We also have different types of T-cells located in specific areas of the brain,” he said. “These immune cells are actually influencing the function of the brain: If this immune system is dysfunctional, for example, this will affect memory and also the behavior of mice.”

How can scientists wake these cells back up and get them up to speed? Proteins called immune checkpoints help T-cells decide whether or not they need to activate themselves by acting as a giant off switch. Antibodies that target immune checkpoints prevent the T-cells from being turned off, keeping them on guard and promoting beta-amyloid clearance in mouse models.

“What we are trying to do by using the immune checkpoint inhibitor is actually rejuvenating the immune system, boosting the activity of the immune cells,” Croese said.

The first T-cell-based strategy for treating Alzheimer’s involves stimulating the brain’s immune system. ImmunoBrain Checkpoint has now commenced the first clinical trials of an antibody-based drug targeting the checkpoint inhibitor on T-cells in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and are also planning to run a trial for frontotemporal dementia in the future.

Another strategy involves tamping down on damaging inflammation and helping harmonize the activity of the immune system in the brain. Another company called Coya Therapeutics is developing another treatment focused on subtypes of T-cells called regulatory T-cells (Tregs). Their strategy involves taking Tregs from an individual, growing more outside the body, and injecting them back into the body.

Keeping the microglia in sync

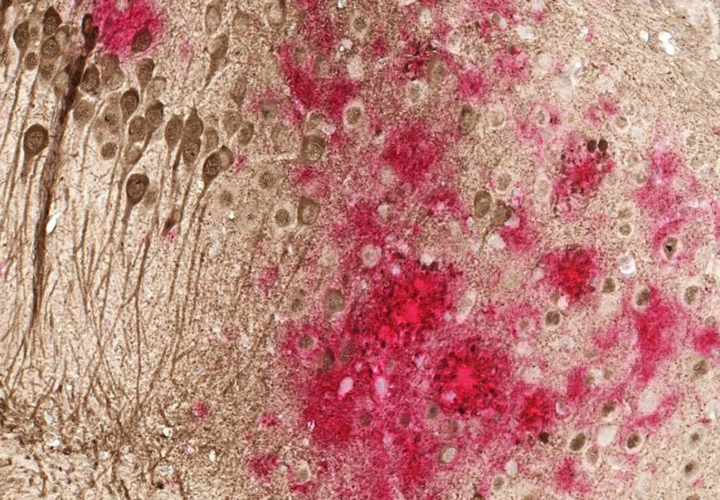

Microglia are the other critical immune regulators within the brain and have been studied more than T-cells in the context of Alzheimer’s. These are small cells with many tiny arms that probe around the brain. In the presence of damage, debris, or infection, these cells transform: They retract their arms, become rounder, and start working to protect the brain.

But the problem is microglia aren’t always playing the right song. Microglia can do various actions depending on how they are activated. Brigham Young University professor David Hansen told Being Patient that monoclonal antibodies like Leqembi “make the microglia think they are fighting a microbial infection,” which could inadvertently cause harmful forms of inflammation and damage to neurons.

In contrast, a new class of drugs focused on activating the microglia could “promote a type of microglia activation that mimics the natural, non-inflammatory microglial response.” As a result, it would allow for amyloid plaque clearance that would minimize potentially harmful side effects like ARIA.

A lot of research has focused on activating a protein called TREM2, which activates the microglia in animal models of Alzheimer’s. This protein helps set off a cascade of molecular machinery that clears beta-amyloid in the brain. Some variations of the gene that encode this protein and disrupt its proper functions are also a genetic risk factor in humans. Activating TREM2 directly, Hansen believes, would be a more effective way to activate the brain’s immune system rather than using anti-amyloid antibodies. “It’s not just whether microglia are activated or not, but the manner of activation that really matters,” Hansen said.

Drugmakers Alector and Abbvie are testing an antibody-based drug called AL002, which activates the TREM2 receptor on microglia to clear out plaques, in Phase 2 clinical trials. Taking the opposite approach, True Binding’s drug TB006, also an antibody-based drug, attaches to a sugar on the surface of microglia to tamp down inflammation and hit the brakes on the microglia.

Microglia also have immune checkpoint proteins, like CD33, that have variants that confer a slight increase in Alzheimer’s risk. However, drugs that block or activate these proteins haven’t yet been tested in humans.

Recruiting fresh ‘Natural Killers’ to the orchestra

What happens when players in the orchestra start to falter or retire as they can no longer keep up with the music? When the immune system fails, diseased cells start to fester causing more inflammation and disruptions in the brain.

Normally, natural killer (NK) cells are the part of the immune system that get rid of dying and damaged cells but as they age, they too become less potent, making the brain susceptible to Alzheimer’s disease.

NKGen CEO Dr. Paul Song is taking a relatively unique approach to solve this problem. Song told Being Patient that in Alzheimer’s, other immune cells aren’t as good at telling the difference between healthy and diseased cells, leading to a lot of collateral damage. Instead of developing drugs that rejuvenate the NK cells, they can take these cells out from a person’s blood, multiply them, and train them to once again live up to their moniker.

At this year’s Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference (CTAD), the company presented human data from ten patients with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s as part of the proof-of-concept Phase 1 clinical trial. This was the first-ever trial testing NK cells in humans.

“When we gave our NK cells through an IV, they crossed the blood brain barrier and they removed both amyloid proteins as well as tau proteins,” Song said, adding that the patients who received infusions of their own NK cells had reduced levels of several inflammatory biomarkers. Eleven weeks after these infusions, almost all of the patients in this preliminary trial remained stable or showed improvements in cognition according to standard Alzheimer’s assessment scales.

Song said that they will continue to follow these patients along and will enroll new patients for its next clinical trial in the next few months.

By harnessing the power of the body’s immune system, scientists developing these new treatments hope to finetune the cellular activity of T-cells and microglia, as well as retrain and rejuvenate NK cells, so that they can effectively clear out disease-associated plaques and proteins without causing excessive damage and inflammation in the brain.

UPDATE, 12 January 2024: The article has been updated to reflect Dr. Tommaso Croese’s current affiliations.

LOVE THE INFO ON ALZHEIMERS BREAK THROUGHS, LOST MY DAD TO IT.CAN YOU PLEASE KEEP US INFORMED WHEN A MEDICAL BREAK THROUGH FOR A CURE OR SOMETHING TO HELP US MANAGE OUR SYMPTOMS

Thanks for being here, Deborah — we plan to keep the good news coming.

Thank you for the updates on these studies. Inflammation and immune system seems to be the root cause of so many diseases. I lost my mom to Alzheimer’s. My husband now is diagnosed with it. He is a Vietnam Vet. I’ve been also reading about how the incidence of Alzheimer’s is higher in that population 2:1. They are looking a link to Agent Orange & how that affects the brain.

Hi Suzanne, thank you for being here! We recently wrote an article exploring how veterans exposed to Agent Orange might have a higher risk of developing dementia. You can find it here: https://www.beingpatient.com/should-the-va-add-dementia-to-its-list-of-illnesses-caused-by-agent-orange/