What if this certain kind of beta-amyloid protein — largely known as a potential cause of Alzheimer's disease — is actually a good thing? Dr. Alberto Espay explains.

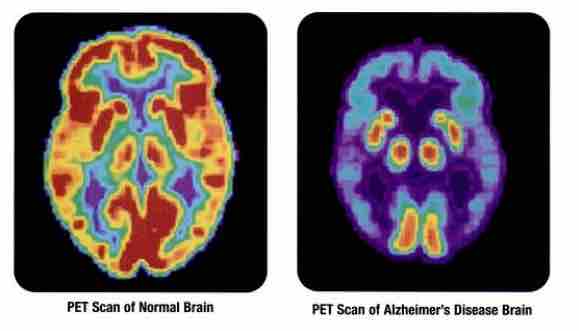

For decades, scientists blamed Alzheimer’s disease on the buildup of beta-amyloid protein plaques in the brain. But most clinical trials for drugs intended to treat Alzheimer’s by flushing out these problematic proteins have failed.

While two of the relative successes in the “anti-amyloid” drug space — monoclonal antibody drugs Leqembi and Kisunla — are approved by the FDA, they only slow cognitive decline down by a small amount. Researchers are split on whether they’re worth the risk, and regulators in a number of other countries are saying no to them altogether.

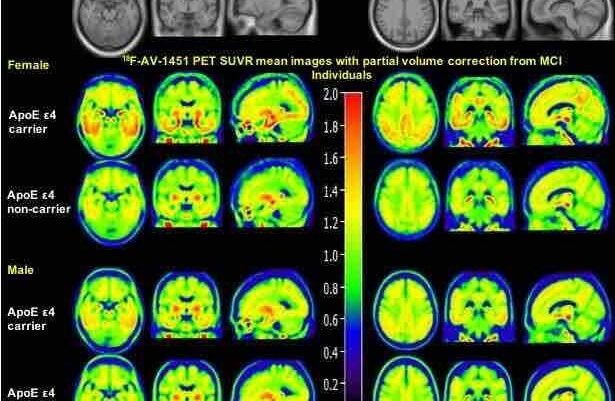

While many drugmakers are developing drugs to eliminate beta-amyloid, Dr. Alberto Espay, believes that a beneficial form called Aβ42 might be protective. In 2021, the University of Cincinnati neurologist found that higher levels of Aβ42 might be protective in healthy older adults who are amyloid positive. Recently, he took notice of a peculiar property of amyloid-clearing drugs: They increased the levels of Aβ42.

Now, a new study published in Brain by Espay and colleagues posits that anti-amyloid drugs actually work not by getting rid of bad amyloid like drugmakers had thought — but by consequently increasing the levels of this good amyloid, Aβ42.

Espay and team analyzed data from 26,000 study participants enrolled across 24 different trials of various anti-amyloid treatments. What they found: The participants with the highest levels of Aβ42 had the slowest rate of cognitive decline at the end of the trial.

The anti-amyloid drugs might prevent the healthy forms of amyloid from aggregating into plaques, allowing the protein to keep the brain healthy for longer.

Based on these results, Espay argues that the loss of Aβ42 is a bigger driver of Alzheimer’s than the forms of beta-amyloid — protofibrils and plaques — the developers of these “mab” anti-amyloid drugs have been so obsessed with eliminating.

“The large number of people who have amyloid plaques but no cognitive problems suggest that keeping Aβ42 at a high level must be important,” he said.

Simon Mead, a neurologist at University College London Hospitals, who wasn’t involved in Espay’s study, commented on the findings on Twitter/X, writing that it’s “good to promote alternative mechanisms” for Alzheimer’s disease and treatments.

By age 85, fewer than one in three amyloid-positive individuals develop the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

In contrast, Espay says that everyone with low levels of Aβ42 goes on to develop cognitive symptoms.

Espay hopes these findings clarify that restoring levels of Aβ42, rather than reducing beta-amyloid plaques, could be a new frontier in Alzheimer’s treatment. Regain Therapeutics, the company he cofounded, operates on this platform, aiming to develop treatments that elevate this protective form of amyloid — though they have yet to test these drugs in human trials.

This type of research is indicative of a shift in Alzheimer’s research away from the idea that amyloid is the sole cause of the disease — which dominated research for decades — as researchers and drug companies are looking into other strategies, like increasing the levels of Aβ42 to treat the disease.

My mother had dementia and died. Now, I have noticed that I can’t seem to talk right. I am under a doctors care and I am taking CelecoXIB I am scared. I used to be good with numbers. I was working at a college but retired a few years ago,

Hi Paula, Thank you for sharing your story with us. It’s understandable to feel scared when noticing changes like this, especially with a family history of dementia. There can be many reasons for cognitive changes, and taking steps like staying informed and seeking support is so important. Take care.