Can you inherit dementia? Scientists discover new genes associated with Lewy body dementia and FTD. Learning what these genes do is the first step toward developing preventions and treatments.

Alzheimer’s disease is responsible for 60 to 80 percent of all cases of dementia, and to date, most dementia research and treatments have focused their efforts here. But, there are more than 100 other forms of dementia out there. Because so much research has focused on Alzheimer’s, scientists have gained major ground on untangling the complex role of genes in driving the disease: For example, the APOE4 genetic variant is one of the best known genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s. Carrying one copy of the APOE4 gene increases the chances by increasing chances by 25 percent, while carrying two copies raise the risk at least three times over. Other genes and variants, like APOE2, seem to have the opposite effect: protection. So, what if researchers could unlock the genes that seem to cause — or protect people from — other common forms of dementia?

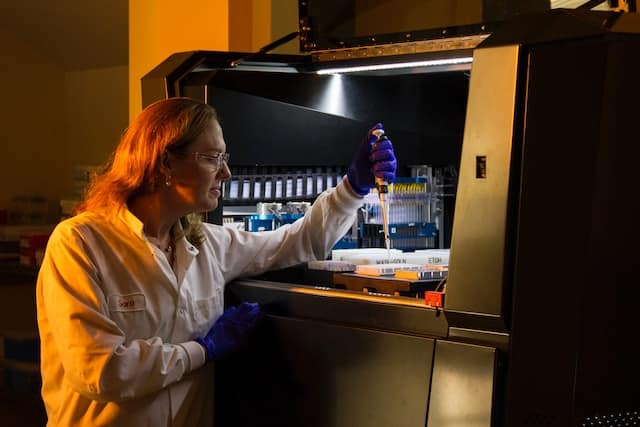

Neurodegenerative diseases including Lewy Body (the kind of dementia that actor Robin Williams had) and frontotemporal dementia (the kind of dementia that actor Bruce Willis is living with now) affect more than 10 million people around the world. As the cases of dementia are set to triple by 2050, the amount of people with non-Alzheimer’s dementia will continue to increase. Sonja Scholz and her team at the NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke carried out a study to try to crack the genetic code on these two diseases.

“The genetic underpinnings of non-Alzheimer’s dementias are poorly understood,” Scholz told Being Patient. “Our study is an important step toward mapping the genetic architecture of these understudied diseases.”

Understanding the genetics of non-Alzheimer’s dementia

Scholz at the NINDS’s neurodegenerative disease research unit and colleagues sequenced DNA from a total of 9,345 people broken out into three groups: 2,612 people with Lewy body dementia, 2,601 people with frontotemporal dementia, and 4,132 controls.

Genes spell out instructions for making specific proteins in the body. When a gene’s instructions are wonky: for example, chunks of information are missing, duplicated or inverted, the result is what’s called a “structural variant” on that gene. Scholz and her team hunted for hard-to-spot structural variants that could give them clues into why study groups had one kind of dementia or another.

In general, structural variants are very common. From their study sample, the researchers found 160,000 different variants among their 9,345 study participants.

Most of the time, these variants aren’t associated with any particular disease. Think about these variants like the genes that determine traits like eye color. Some people will get the gene that makes eyes green, while others get the gene that makes them blue.

In this case, Scholz and colleagues were interested in variants that seemed to be more common among the group with Lewy Body dementia, or among the group with FTD, than they were in the control group.

Is FTD genetic?

Answer that question, note past research, then share their findings.

What they found was that genetic variants in two other genes — C9orf72 and MAPT — were associated with 20 percent of frontotemporal dementia cases. Earlier research linked the C9orf72 gene to the severity of symptoms with FTD patients carrying the variant having more delusions and more severe cognitive impairment. MAPT variants are also shown to affect FTD symptoms — some variants lead to more forgetfulness while other variants are linked to cognitive dysfunction.

What about LBD?

When it came to Lewy body dementia, they found another significant genetic difference: eight percent of participants with Lewy body dementia carried a never-before characterized variant in the TPCN1 gene. This builds on previous work from Scholz which identified five genes associated with LBD: SNCA, APOE, GBA, BIN1, and TMEM175.

The findings are published in the journal Cell Genomics. Scholz explained that while these three genes serve an important role in keeping brain cells healthy, these variants prevent these genes from doing their job. But, she added, it isn’t clear why these specific genetic changes are linked so strongly to the disease. Is it because an important part of the cell stops working allowing debris and cellular waste to build up, causing toxicity? Or do these genes start producing harmful proteins from the get-go?

Scholz and colleagues are currently recruiting participants for clinical trials to learn more about these genetic variants and their associations with Lewy body and FTD dementia.

Why does this new dementia gene discovery matter?

As more data comes in, researchers will be able to develop drugs that target genes driving non-Alzheimer’s dementia.

In Alzheimer’s, there are already two FDA-approved treatments that may slow disease progression at the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s — Aduhelm and Leqembi — with dozens of other drugs in late-stage clinical trials. These drugs are borne out of understanding the genetic underpinnings of the disease. First reported in 1987, people with inherited forms of the disease had mutations in genes associated with the amyloid protein. These mutations lead to the increased buildup of amyloid plaques in the brain. When the genes were inserted into mouse and rat models, the amyloid plaques built-up in their brains, affecting the animal’s memory and cognition. All this work put a bullseye around the beta-amyloid protein, with scientists targeting its removal with new types of drugs, like Aduhelm and Leqembi.

According to Scholz and team, figuring out which genes are linked to Lewy body and frontotemporal dementia is a first step toward developing new drugs: “Identifying and characterizing the exact mechanisms by which these genetic changes disrupt key cellular processes is at the core of ongoing research efforts,” she said. Expanding our understanding of genetic factors in other types of dementia, she added, can “pave the way for developing targeted treatments.”

My mother had LBD. Is there anything I can do as a preventive measure? It’s a horrible disease.

I was diagnosed with MCI on Dec 8, 2022. I have a family history of alzheimer’s father, paternal aunt, paternal 2nd cousin.

Suspect same age, 1st cousin has Alzheimer’s.

I am very interested in ongoing studies focused on the source of the disease. Not interested in studies on medication for behavior management.

My mom an all her sisters had an aggressive dementia an I’m very concerned about getting it Is there a test I can do???

Robin, with your family history, it’s reasonable to be concerned. There are some early detection tests, though more research is still needed. We suggest speaking with your doctor to look at your options going forward. Here is an article you may find useful in the meantime on screening to improve early detection: https://www.beingpatient.com/screening-for-dementia-in-primary-care/