Steph Jagger, whose mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer's at the age of 67, shares the lessons she learned from love, loss and acceptance.

It’s tough letting go of life as we know it. Reconciling with the fact that Alzheimer’s takes away our loved ones’ memories, their ability to recognize those around them, and so much more, is heartbreaking. But stepping into a person’s reality, as difficult as it may be, could open one’s eyes to what remains beyond the disease.

That may be the joys of companionship, the beauty in sharing new experiences, our silent communication with one another and nature, or the indelible marks that our loved ones leave behind.

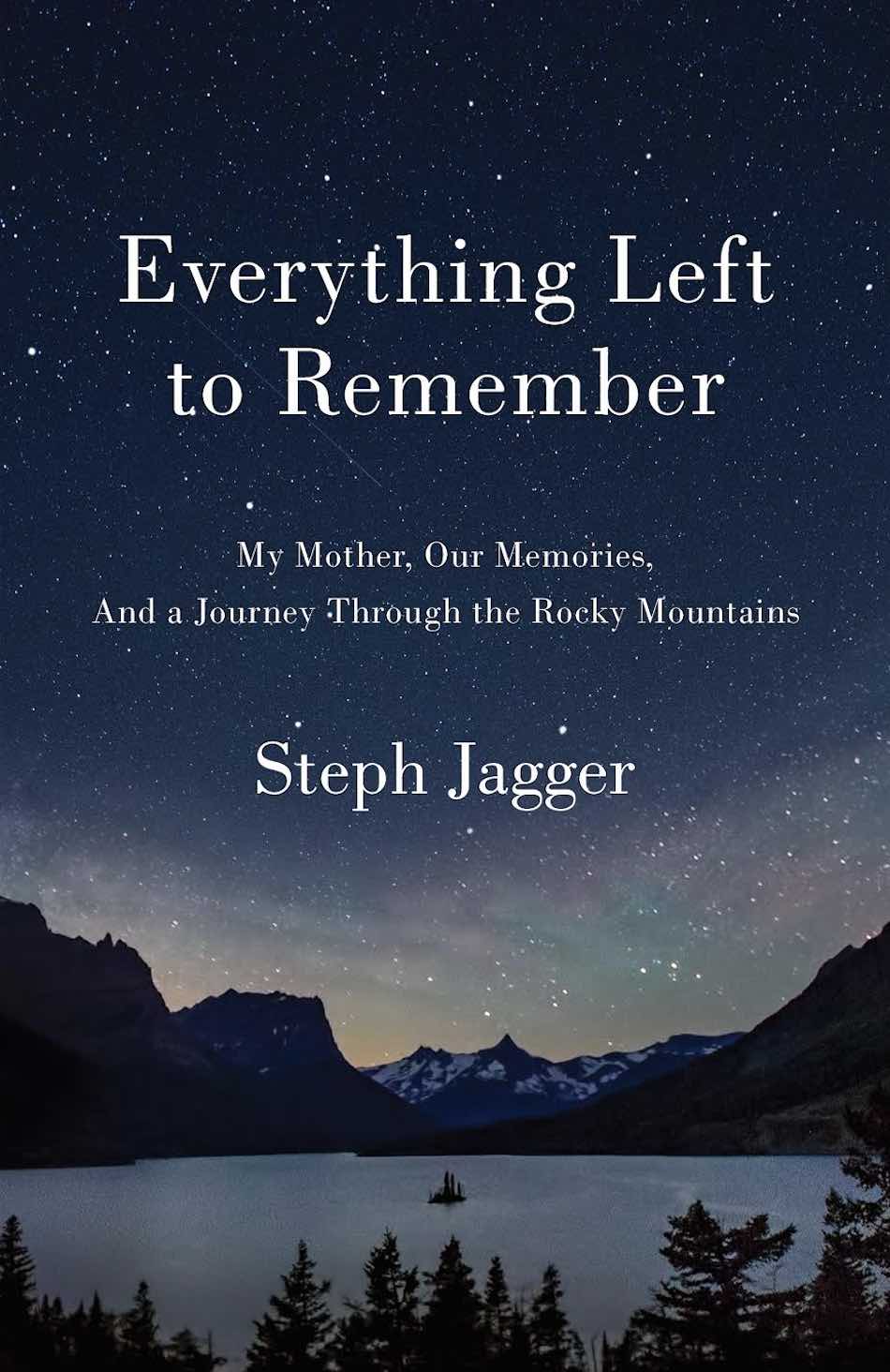

In a LiveTalk with Being Patient, Steph Jagger, author of Everything Left to Remember: My Mother, Our Memories, and a Journey Through the Rocky Mountains (April 2022), shares her family’s experience with her mother Sheila Jagger’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis in 2015.

Reflecting on a road trip she took with Sheila 11 months after Sheila’s diagnosis, Steph recalls their adventure across three national parks. She also shares guidance on traveling with a loved one with dementia.

As Steph looks back on the family’s journey with Alzheimer’s thus far, she speaks about grief, the process of letting go and embracing her mother’s reality.

Being Patient: Tell us a little bit about your mother’s symptoms of Alzheimer’s that you started to notice around 2012.

Steph Jagger: For my mother, some of the very early signs were simple forgetfulness: not being able to say certain words, losing people’s names, not remembering details of what we did the day prior, stuff like that. In combination with those, I started to notice what I would call early coping skills. She got very good at saying phrases like, ‘Oh, I knew that,’ or instead of saying somebody’s name, she’d say, ‘Oh sweet person, come over here.’

I had a bit of a unique perspective because I wasn’t living with her. I would come home every three, four or five months and notice more dramatic differences than one would if they were living with somebody day-to-day and there was a really slow decline.

One of the tipping points for me was a change in personality that showed she had lost her filter. She said something to me one day that made me quite mad. As I was reflecting upon it, I stopped myself and thought, ‘That’s not my mother. I know her and that’s not how she would normally react.’

I looked backwards and connected the dots with all the other things I was seeing and went, ‘There’s something really going on here.’ From that stage, [I] reached out to a handful of other family members to ask, ‘Are you also noticing these things?’

Being Patient: At the same time, your maternal grandmother was living with dementia. What was that like for the family and what was your mother’s role in caring for her?

Steph Jagger: That was really excruciating. My maternal grandmother had old-age dementia and Alzheimer’s. She lived on her own into her 90s, but probably started showing some signs of dementia in her late 80s and was then moved into a care facility in her 90s and lived her life out there.

My mother as well as her sisters weren’t hands-on caretakers with their mother, but they were at her place almost daily. They would rotate to make sure there were groceries, the dog was watched, the bills were being paid, [the] checks [were] being signed and various things. They stepped in as a team to make sure that her life was still functional.

My grandmother ended up passing in January of 2015. My mother had been showing signs already for three-ish years until that point. Then, my mother was diagnosed in June of 2015. I think part of the hesitancy to see if there was a cognitive decline happening and to get a sense of that early was because she was witnessing it in her mother.

I can’t think of anything more excruciating than seeing live the path that you are probably going to walk down and are already a ways down, and thinking if you get a diagnosis early, the family will then be caretaking for both people at the same time.

On grief, loss and letting go:

Being Patient: You wrote that everyone experiences their unique losses; when people are consumed in their own losses, they can lose sight of what others are going through. What helped open your eyes to the losses of those around Sheila?

Steph Jagger: [David Kessler said], ‘The worst loss is always your own.’ When we have that sense of grief and sense of loss, our vision does shrink and we put blinders on, because it’s almost too much to think about what’s going on outside of that.

I read a book about loss and grief called Modern loss. [It’s] a collection of essays, and one of them focused specifically on collateral grief. It is the grief that you experience say of the person in front of you. The grief that I have over the loss of my mother is my own direct grief. There’s a collateral grief that happens in a situation [where] my dad is going to be consumed with caregiving for one to seven years, and because he’s concerned with that, I will also lose a specific part of my relationship with him. When I read about that, it opened me up to [thinking], ‘Oh, there [are] different types of grief within myself, I wonder if that means there [are] different types of grief going on in other people.’ The answer is yes. The answer is fairly obvious.

I don’t know that I do this with a lot of grace, but I attempt to create space for the idea that other people are losing something distinctly different than you. Sometimes, [it’s] the same. As an example, I’m the only child of my parents who doesn’t have their own children. I’m dealing with the grief of the loss of my mother, but I’m not dealing with the grief of the loss of my children’s grandmother, whereas my siblings who all have children are dealing with their grief and the grief of the loss of their children’s grandmother.

The other thing that I’ll add is a dear friend of mine gave me a piece of advice. She’s in her 60s and is twice widowed. She taught me a lot about what it was to lose a spouse and what she called the mourner-in-chief … She felt that [the] relationship [between her and her spouse] should be respected in a bit of a different way [than the relationships between her spouse and others]. That helped me frame the spaciousness and grace that I wanted to offer my father as he took on the role of mourner-in-chief.

Being Patient: Your mother, Mother Nature and Alzheimer’s have all taught you lessons in surrendering. For you, what does it mean to surrender?

Steph Jagger: With my mom, our relationship and my experiences in nature, I spent a lot of time as a young woman and certainly at the beginning stages of Alzheimer’s, which include different types of grief, attempting to control what was going on.

If my mom would forget a detail or she would get something wrong, my go-to was to correct her to control the narrative of what was going on, to control all the different emotions that I was feeling which were very uncomfortable. That’s pretty natural when there’s something that makes you feel so out of control.

When you venture into nature, it can be a little bit of a scary place where I don’t know what’s going to happen.

“As her reality begins to shift over time,

will I let it or will I cling painfully

to the reality that I want?”

There’s a similar message [between nature and Alzheimer’s]: If I feel that I need to step in and control something, that’s probably a sign for me personally that there’s a lesson in [surrendering] and holding space. Perhaps something larger, something more important, a bigger energy, would like to reveal itself. If I can loosen my grip on the different reins that I believe I have in my hands, then I might have the opportunity to learn something.

Being Patient: You wrote about an interaction between you and your mother in the morning of flying out for the camping trip. Can you tell us more about this interaction, and how it serves as an example of surrendering to the reality of Alzheimer’s?

Steph Jagger: We were at the top of the staircase in our family home and I said, ‘Morning Mom. I love you.’ She looked at me like [she was thinking], ‘I think I know who you are, but I don’t know who you are. You’ve just said that you love me, so I probably love you too.’

You could sense there was a bit of a calculation going on, and she said, ‘I love you too,’ like [she was thinking], ‘This is what I’m supposed to say, but I don’t really know why I’m saying this.’ That kind of situation, as well as the first time or the first handful of times where a loved one forgets your name, can be really, really excruciating moments in our journey with Alzheimer’s and dementia.

This goes back to your brilliant question Nicholas about surrender. If my mother is going to be forgetting who I am or forgetting why she loves me, am I going to try and cling to that and do something like quiz her or tell her? I could have stood at the top of the stairs and said, ‘Oh Mom, the reason you love me is I’m your daughter. I was born [in] xyz. We’ve had all of these memories together.’ I could have tried to instill my reality on her shifting reality, or I could surrender to [her reality].

For me, the ultimate [realization] was: I need to surrender to the fact that my mother is no longer going to be able to mirror my own identity in the world. I need to allow her to go on that journey, lose those memories and lose that ability to reflect my identity back to me.

Then, I have to do the work of reflecting my identity back to myself. Do I love myself? Do I know my name? Do I have people around me who can begin to pick up the mirror that she’s metaphorically placed on the ground? That was an important part of the process and really, really speaks to the example of what I mean by surrender. As her reality begins to shift over time, will I let it or will I cling painfully to the reality that I want?

On traveling and dementia:

Being Patient: Can you run us through where you and your mother went for the camping trip?

Steph Jagger: We were on the road for about two weeks. We flew from Vancouver, Canada, into Bozeman, Montana and rented a car there. From there, we did a loop through three different states and three different national parks. We started in Yellowstone National Park. We went to Grand Teton National Park and Glacier National Park. We mostly camped … and we went horseback riding a couple times. We went in a gentle whitewater raft. We did a lot of walking, hiking and different activities in the national parks. It was beautiful.

“She may not remember a fact, but if her body, emotion

and sense of self are still carrying joy about an

experience that she had yesterday, 10 days ago,

or just a moment ago, that can create such an ease,

and a sense of longevity and hope for all of us.”

My mother has always been a very physically fit and athletic person, and really loved the outdoors, probably more so than my father. They didn’t spend a lot of time outdoors in that way. I thought she would love it. I thought she would be ecstatic about being able to see bison, and different streams and mountains in nature. That was certainly the case. She really, really enjoyed being in nature.

Being Patient: Do you have any advice for traveling with a loved one with dementia?

Steph Jagger: Traveling with and being with [a person with dementia] in general are probably the same things. The first [tip] would be to be prepared to answer the same question over and over again. My mother would ask a specific question, forget that she’d asked it and ask it again.

The second would be what I would call a humorous redirect. If my mom was stuck on a particular question, eventually I would try and redirect her. There’s one example in the book where she was asking over and over again where we were. I decided to remove the map from her hand and remove the different books she was holding in the passenger seat of the car, and asked her if she could help me by counting red cars. That seemed to work. She talked about red cars for the next hour or so.

Another tip whether you’re traveling or not — and this is really, really popular within the Alzheimer’s and dementia community — is to borrow a skill from improv. In the improv world, there’s something called, ‘Yes, and …’ There [are] two partners who are doing a comedic scene and one of them offers something to go with, a version of their own creative reality. The rule is to say yes, and then add to that. Accept the gift that this person has created and accept their version of reality, and add to it.

If my mother said something like, ‘Those clouds look like they’re whipping cream animals.’ I would say, ‘Yes, I think they would be delicious on top of some ice cream,” instead of saying, ‘No, Mom. Those are not whipping cream animals. Those are clouds and they’re in the sky.’ It will help with a couple of different things. One, it makes for a more pleasant atmosphere, and more pleasant feelings, emotions and sensations within our body. Two, [it] goes to what we’ve been talking about throughout this [interview], which is the idea [that] they are living in [a] shifting reality, and how do we work to best go with that?

The third tip that I would give … is to be a little bit more vocal and inform people around us [about a loved one’s impairment]. I did this on a handful of occasions but I would have done it more.

Being Patient: For instance, people could tell a tour guide to keep an eye out for their loved one.

Steph Jagger: That’s right, and being very upfront and clear with them. There was one instance where I didn’t do that, and one where I did. The one where I did, I felt so much better. I was able to say to the guide, ‘The safety instructions that you’ve just given us, she will not remember. What can we do as a team to make sure that we’re all safe whitewater rafting?’

Being Patient: After returning from the camping trip, your father asked about the trip’s highlights, but your mother couldn’t recall any details of the trip. How do you make sense of that? Again, does approaching this reality involve surrendering to things that are beyond our control?

Steph Jagger: Certainly, it speaks to the idea of surrender, but also to something that I’m such a big believer in … What makes us extraordinary as human beings is that we live inside of [stories] and [emotions]. She may not remember a fact, but if her body, emotion and sense of self are still carrying joy about an experience that she had yesterday, 10 days ago, or just a moment ago, that can create such an ease, and a sense of longevity and hope for all of us.

A lot of people, when the person they know that has Alzheimer’s is in a care facility, say, ‘Well, I don’t want to go visit because there’s really no point. She won’t remember the visit. She won’t remember who I am, etcetera.’

I [say], ‘But they will register how you’ve made them feel, and if that means they carry a feeling of joy through the next three hours, through the next 12 hours, I really think that can make a difference for people.’

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com

As the sole caregiver to my Bride of 61 years, this article was refreshing in that it helped me to become more accepting of the disease rather then the condemnation and search for cures.