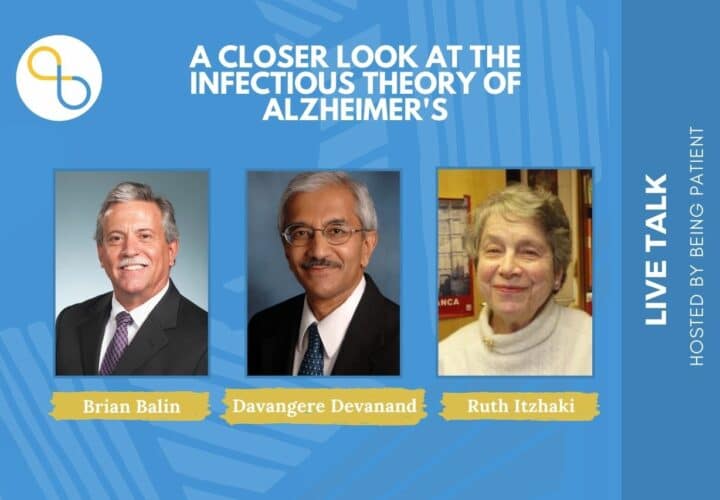

Credible evidence shows germs may lead to Alzheimer’s. Intracell Research Group Founder and Alzheimer’s Pathobiome Initiative Co-Founder Nikki M. Schultek calls for consensus and collaboration around a new approach to Alzheimer’s and dementia research — one that drills down on cases driven by infection.

Last month, a ground-breaking research roadmap was published in Alzheimer’s and Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, entitled “Establishment of a consensus protocol to explore the brain pathobiome in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.” This scientific publication is the first milestone of a new collaboration called The Alzheimer’s Pathobiome Initiative (AlzPI) — the first interdisciplinary, global effort to advance our understanding of the role of infections (germs) in Alzheimer’s disease.

For over three decades, most researchers in this niche have been trying to answer two questions:

- Can infection(s) cause Alzheimer’s for a subset of patients? and

- What germ(s) are to blame?

The concept is actually very simple; an infection or multiple infections are driving the inflammation, plaques, tangles, and symptoms seen in Alzheimer’s.

After all, infections are known to be the number-one source of inflammation in the human body. As straightforward as that sentence sounds, it is probably one of the most challenging scientific questions to answer: Does “germ A” cause “X disease”?

Why is it so challenging to prove the link between infections and Alzheimer’s?

The fact that Alzheimer’s affects the brain — an encased, relatively inaccessible organ, — makes research exceedingly complex. While germs are known to cause diseases and inflammation, the idea that they get involved in chronic inflammatory diseases has remained somewhat elusive (with certain exceptions, like the case of a bacteria called H. pylori that causes ulcers and some GI cancers).

The difficulties in establishing cause here lie in the behaviors and capabilities of the germs themselves, as well as the makeup of the human immune system, which comes in many different variations. In other words, “germ A” might be very prevalent, infecting many humans, but it only leads to chronic disease in certain individuals (like the many examples COVID-19 has provided).

Another fundamental obstacle is the configuration of medical research into distinct fields that do not readily cross-pollinate. This has led to a lack of progress in understanding a disease which is clearly very complex and multifactorial.

So, how can we make sense of the data we do have about the relationship between germs and Alzheimer’s, so that it can benefit patients?

It may be at the intersection of the human immune system and our diverse microbial passengers, also known as the microbiome or pathobiome (to describe harmful germs) that we see the murky waters of chronic inflammatory diseases — including Alzheimer’s and other dementias — begin to clear.

This Alzheimer’s research niche has gained considerable momentum since the COVID-19 pandemic started in late 2019. But still, there is an urgent need for collaboration between distinct research silos if we are to identify a subset of patients that have treatable or preventable infection(s) driving their individual case of Alzheimer’s.

Are we asking the right questions?

Let’s revisit the questions being asked by the research field: Can infection(s) cause Alzheimer’s in certain patients? And which germ(s) could be to blame? Those might not be the right questions.

Instead, credible research suggests we should be asking: Should infectious diseases be on the list of things to “rule out” (in doctor speak the “differential diagnosis”) in patients at the first signs of cognitive decline?

Different types of research have been conducted in an effort to clarify this link between germs and Alzheimer’s, but none of it has established a definitive causal relationship. However, collectively, the weight of the evidence is quite compelling. Let’s review it.

Research looking back on large human populations over time (a.k.a. epidemiology)

People diagnosed with serious infections requiring hospitalization, like meningitis and pneumonias, do face a significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s.

Large database studies reveal that people who were prescribed antiviral drugs (for viruses) and antibiotics (for bacteria) appear to have a reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

There is an urgent need for collaboration

between distinct research silos if we are

to identify a subset of patients that have

treatable or preventable infection(s) driving

their individual case of Alzheimer’s.

Studies have also suggested that certain vaccines can actually reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s in a population. However these studies are difficult to interpret as people that got their vaccines may have also engaged in healthy behaviors relative to their peers who did not get vaccinated (diet, exercise, visits to the doctor and many others).

On the whole, large, retrospective, population-based studies are unlikely to provide adequate evidence that germs can cause Alzheimer’s — or provide actionable solutions.

Studying the brains of people who died with Alzheimer’s

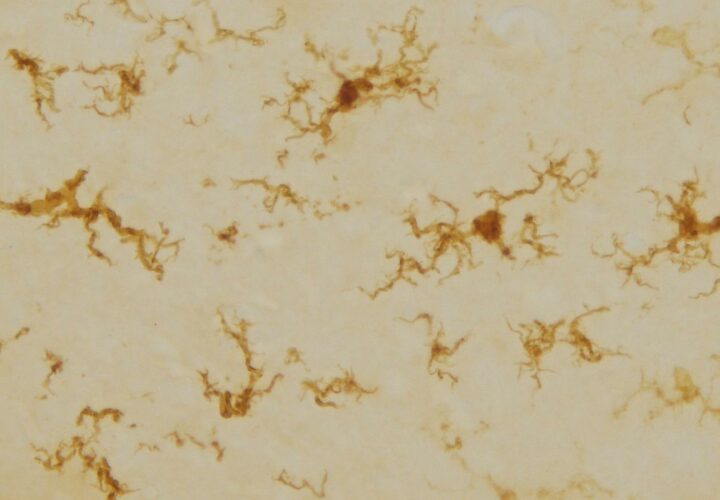

Another way to study this disease is to examine brain tissues of patients who died of Alzheimer’s.

It turns out that certain deleterious germs are present in greater numbers in Alzheimer’s brains compared to brain tissues from people the same age without Alzheimer’s. In fact, some of the germs repeatedly associated with Alzheimer’s and found at the scene of the crime, possess skills and behaviors that make them prime suspects.

For example, the virus that causes cold sores (Herpes Simplex Virus 1 and 2), the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi that causes Lyme Disease, a prevalent bacterium that causes respiratory tract infections and pneumonia called Chlamydia pneumoniae, and the bacteria Porphyromonas gingivalis that causes gingivitis, all have the ability to impact the brain and cause neuro-inflammation and/or release toxins capable of inducing a powerful immune response.

However, on its own, this type of research still does not demonstrate that the germs are in fact causing the disease. What about the plaques and other hallmarks present in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients?

Human genetics and the immune system

A truly important piece of evidence has given us a clue about the origin of Amyloid beta (the substance that forms these plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s). Contrary to what you have been told, Amyloid beta may not be “bad.”

A beta is something manufactured by the human body to combat infection and other insults. Monoclonal antibodies that successfully remove amyloid are not very effective at slowing disease progression — and they do not reverse or stop the disease. This might be because amyloid is serving an unappreciated purpose, and in order to stop the disease we need to understand why it is there in the first place. An upstream intervention that addresses infections coupled with treatments to clear amyloid may eventually be tested.

Another piece of evidence is provided by the “Alzheimer’s gene.” It is known that people with two copies of a gene variant called APOE4 are at an elevated risk of developing the disease and may fall victim earlier in life. However, most people aren’t aware that this gene leaves carriers more vulnerable to certain infections that have been associated with Alzheimer’s and with severity of and susceptibility to COVID-19 infection.

Taken alone, these findings do not reveal whether infections cause this disease, so researchers have attempted to recreate the process in animals.

Animal studies exploring germs and Alzheimer’s

In order to mimic the cascade of events taking place in the human body, researchers have used infection models in animals to better understand how germs impact the brain. Very compelling studies have shown that giving mice strongly-associated germs leads to Amyloid beta-like plaques and cognitive decline in the animals.

The pathways from nose to brain and mouth to brain have also emerged as very important routes indicating that infections in either of those locations may impact the brain either by direct invasion or by causing a powerful immune response that leads to damage.

However, like the other forms of research, animal models have their limitations and are unlikely to provide adequate proof that germs can cause Alzheimer’s in certain patients. Infecting another species doesn’t truly replicate what happens in the human brain over a lifetime of infections and inflammatory immune responses.

To better understand how to advance this hypothesis, our team scoured the medical literature. We found something truly important in the context of other evidence.

Case reports of individuals with infections causing “reversible dementias”

Our global interdisciplinary team has documented nearly two dozen case reports of “reversible dementia” in the medical literature. These are patients who had various dementia diagnoses (including Alzheimer’s), then their doctor decided to order a spinal tap (also known as a lumbar puncture) to test their cerebrospinal fluid (the clear liquid that surrounds and cushions the brain and fills the spinal cord) to look for evidence of infection.

In each of these cases, infections were revealed, however they were quite diverse. Some had fungal infections, some bacterial, some viral, some parasitic, and some were mixed (more than one type present at the same time). And in each case, a precise treatment was started to target the germ that was found in that individual patient.

Most of these people had a drastic improvement in their memory scores, some of them returning to “normal.” This kind of evidence is very compelling and suggests that infections should be on the radar, but case reports alone will not advance science. It is also important for the public to understand that not all doctors publish their cases. Many are too busy to publish, and anecdotal findings will never be documented in the medical literature.

At what point does the collective weight of all of this evidence push us to act in a disease with such a devastating toll on human life and no effective treatments?

Reframing the study of Alzheimer’s

By jumping over to the study of germs that acutely infect the brain/central nervous system that can manifest with cognitive impairment and other chronic neurological symptoms, our team has joined forces to reframe the question using established medical science from another silo: infectious disease research.

When an individual suddenly has a change in mental status or cognition, a number of conditions fill the emergency health care provider’s mind as they begin ruling them out, one by one.

On that list are brain/central nervous system infections, like meningitis and encephalitis. That patient will be sent for brain imaging and they may perform a lumbar puncture to collect cerebrospinal fluid. Blood will also be collected, and all of these samples will be sent to the hospital microbiology lab. There, they will use a variety of different tests to determine whether there is inflammation and if there is an infectious disease present.

Detective work is the critical key here. Meningitis and encephalitis are not caused by one single germ, so the treatment is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Acute infections like meningitis can be caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites. Each different germ requires a tailored treatment. Improper antimicrobial drug selection leads to delays that may result in permanent damage to the brain or death. Even when the correct antimicrobial drug is chosen, there may be drug resistance to overcome, and a different antimicrobial may be chosen if the germ isn’t vulnerable to the treatment.

Some germs are notoriously hard to kill, demanding intravenous drugs, sometimes in combination for a prolonged period of time. In spite of this, some people develop a chronic form of this acute infection called chronic meningitis.

Back to chronic brain disease like mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and its most common form, Alzheimer’s disease: Just because the symptoms creep in insidiously over time doesn’t make it any less of an emergency.

Since we know that infectious diseases can produce acute cognitive deficits or worsening of existing deficits (including HIV, syphilis, urinary tract infections in those with dementia, and sepsis) that can improve or resolve with proper antimicrobial treatment, why aren’t infectious diseases on the list of things to rule out in patients for whom the process is deemed chronic?

What separates the patients in the “reversible dementia” case reports from other patients with Alzheimer’s and other dementias is the curiosity of their physician and relatively inexpensive and informative testing of their spinal fluid.

How these patients were approached was dependent on the physician. If something about that patient’s history, symptoms, or their training as a doctor led them to rule out infectious diseases, the patient was identified and treated.

How many people have treatable infections driving their dementia or Alzheimer’s?

The burning, painfully obvious question is this: If infectious diseases were more regularly ruled out as a part of a differential diagnosis in Alzheimer’s, dementia, MCI, and other neurocognitive diseases, how many patients would have evidence of a treatable infection?

No one has attempted to answer this question.

What separates the patients in the “reversible dementia”

case reports from other patients with

Alzheimer’s other dementias is the

curiosity of their physician and relatively

inexpensive and informative testing of their spinal fluid.

If one in three people will go on to develop dementia globally, and there are roughly 8 billion people on Earth, that means 2.7 billion people living now will develop dementia. If even a small fraction of cases are driven by germs, for example 10 percent have a treatable infection, that’s 270 million people who would develop this disease in their lifetime due to a preventable and treatable cause.

Precision and consensus

Precision is the absolute best word to distill this entire idea. We know that within the category of Alzheimer’s, there is a great deal of variability from patient to patient. Ordering some simple testing for microbes and obtaining a detailed history of the patient’s life is likely to unveil a subset that deserves immediate attention: an infectious subset.

A few key questions need to be addressed through thoughtful collaborations to advance this concept.

(1) What is the best obtainable sample from a living dementia patient to test for microbes? Brain biopsies are not feasible, but perhaps spinal fluid or a minimally invasive nasal scraping can accurately reveal the brain pathobiome.

(2) Which exact tests should be performed to reveal the majority of the germs in the sample? They need to be accurate, reproducible, scalable, and accessible to patients. Some germs are difficult to detect and will require multiple innovative approaches.

And finally,

(3) If infections are identified, which antimicrobial drugs will be able to penetrate the brain and kill germs when there is evidence that a patient has an active infection?

New drugs may need to be developed to overcome the difficulties in crossing the brain’s protective shield called the blood-brain barrier, and to eradicate resistant germs.

Bridging research silos

In order to begin addressing these questions, there is an urgent need for collaboration. Bridging the silos that separate traditional Alzheimer’s researchers and clinicians and those that research and treat infectious diseases is essential. Members of Intracell Research Group and various academic centers around the world have come together as a team to address this vastly under-appreciated research topic.

The Alzheimer’s Pathobiome Initiative (AlzPI), is an interdisciplinary team of experts committed to advancing this research by answering fundamental scientific questions that have thwarted progress. By sharing precious patient samples and using multiple state-of-the-art infection detection techniques, we are developing a “consensus approach” that can eventually be used to test patients living with this awful disease for infections. Importantly, this test or panel will need to be widely accessible, so our group is focused on innovations that translate into new, scalable diagnostics and treatments for this unquantified subset.

Perhaps the most important caveat of all is that while we work to develop a novel diagnostic approach to unveil the most germs possible, we have testing today that can be utilized to diagnose infections that may cause certain cases of dementia and Alzheimer’s.

If it were you or someone you love, wouldn’t you want your doctor to rule this out?

There are multiple causes of dementia. We need theories.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1QYU4yn_cFJcovz4H71TYAvzYxytP6Do_

I care for a person with a diagnosis of AD made by exclusion, not having access to specific tests. For a long she had halitosis++ but was in denial about that. Eventually a trip to a dentist cleared the aroma, but I have always wondered if there was a connection with the cognitive defect.

My friend suffers from Reynards and now she has Alzeimers are the two connected?

I find these articles fascinating but have no training or any valuable input. I have worked for 27years with old people, many with Alzheimer’s and dementia and have a husband with age related epilepsy and mild cognitive decline.

I commend the author for such a trenchant presentation of the accumulating evidence for microbes in AD. I will add for completeness that the detection of varied bacteria amongst the AD patients may just be a sign that these individuals are unduly susceptible to infection. Meanwhile, for AD itself, there may be only one causative microbe, and it still awaits discovery.

Would it be a good move to perform a spinal tap at the onset of AD or other forms of dementia? This could eatablish what germs or viruses are present. Then a massive dose of the appropriate Rx could be given??