What is tau protein — and will it define the next generation of disease-modifying Alzheimer's drugs?

Maybe you’ve heard of amyloid plaques, which build up in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. But there’s another protein biomarker in the mix: tau, which tangles around neurons in Alzheimer’s, FTD, and other forms of dementia. Drug companies are working on new drugs to help clear these tangles and treat the disease.

When Alois Alzheimer first studied the postmortem brains of patients who died with progressive memory problems in the early 1900s, he spotted a buildup of beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles. This disease was later named after its discoverer. For decades afterward, researchers had focused on beta-amyloid plaques, which build up in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients early in the disease. But comparatively speaking, they didn’t pay much attention to tau. As a result, many Alzheimer’s drugs — like the new monoclonal antibodies for Alzheimer’s — have been developed to try and clear amyloid plaques.

Through clinical trials, scientists found that clearing amyloid plaques doesn’t completely solve the problem. Even amyloid plaque-busting drugs like Leqembi and Aduhelm only slowed cognitive decline a small bit. In the last decade, they’ve also discovered that tau does a better job of predicting Alzheimer’s disease progression and might even be a more accurate blood-based biomarker of the disease.

Meanwhile, relatively few drug developers have set their sights on tau — until now.

What is tau?

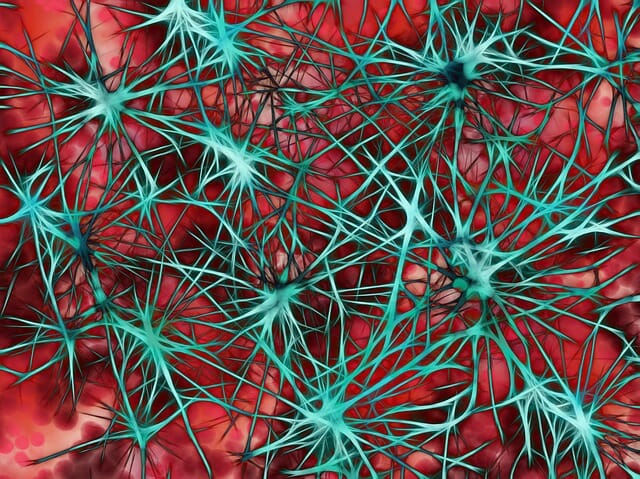

Tau sticks to the inner skeleton of brain cells, helping stabilize these important structures. The skeleton works like a bridge connecting different parts of the cell, while the tau proteins act like the trusses and other supports that keep the bridge stable and standing.

When healthy, tau stabilizes these cellular bridges, allowing it to transport nutrients, chemical signals, and other goods throughout the cell.

But what happens when the supports holding up the bridge start to fail? When tau becomes misfolded, it stops sticking to the bridge and instead starts sticking to other tau proteins, forming what researchers call tau or neurofibrillary tangles. The tangles disrupt healthy cellular function as the bridges that keep the cell healthy collapse.

Some studies find that tau might be a biomarker of Alzheimer’s, but tau tangles aren’t a unique pathology. Bruno Imbimbo, a researcher and Alzheimer’s drug developer at the pharmaceutical company Chiesi Farmaceutici, told Being Patient that it is also associated with other neurodegenerative diseases as well — like frontotemporal dementia and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Can clearing tau tangles treat Alzheimer’s?

Could anti-tau drugs — antibodies sticking to tau tangles and helping the brain’s immune system clear them out — help treat Alzheimer’s disease? We don’t have the answer yet. But, scientists think that tau tangles might be involved in Alzheimer’s progression and symptoms.

“It is unlikely that you can remove the tangles but you can remove the earlier tau pathology which will likely improve cognition or slow cognitive deterioration because tau pathology correlates with cognitive decline,” Einar M. Sigurdsson, a professor at NYU Langone Health told Being Patient. “This will also prevent new tangles from forming.”

But Imbimbo cautioned that we still aren’t sure “whether neurofibrillary tangles are a primary cause of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Something else might cause Alzheimer’s, and these plaques might occur incidentally.

Are there clinical trials for anti-tau antibodies?

If scientists have learned anything from developing anti-amyloid antibodies, success won’t come easy. Imbimbo thinks the road will be “long and could be difficult.” So far, scientists have tested 11 anti-tau antibodies in patients. And so far, most have failed to show promise in clinical trials.

Imbimbo explained that these antibodies only stick to tau found floating in the cerebrospinal fluid but don’t actually target the parts of the protein that tangle up and wreak havoc inside brain cells.

He explained that new drugs are being developed that can get inside brain cells and target the sticky parts of the tau proteins to unclump some of the tangles. The antibodies could cause clumps of tau to break apart and prevent some of the brain cells from dying.

Two of these newer anti-tau drugs have already gone through preliminary Phase 1 trials. Jannsen is currently running a Phase 2 trial of its anti-tau antibody JNJ-63733657 in early Alzheimer’s disease. The trial is slated for completion at the end of 2025.

Drug company Prothena is also developing anti-tau antibodies and recently licensed PRX005 to Bristol Myers Squibb who will conduct a Phase 2 trial in the near future.

Should we target amyloid, tau, or something else?

Alzheimer’s is a complex disease, and scientists are still debating its exact cause. But having multiple treatments for the same disease could be helpful, especially when some people are more prone to side effects from one of the treatments.

An anti-tau antibody may be safer than an anti-amyloid antibody, Sigurdsson said, because it won’t cause brain bleeds (ARIA) as a side effect. These bleeds are a side effect of anti-amyloid treatment that occurs when antibodies stick to amyloid that’s built up on blood vessels, causing them to burst. “Tau antibodies have been safe in clinical trials with no obvious side effects,” he said.

Anti-tau antibodies or any other singular drug alone are unlikely to solve Alzheimer’s disease.

“I think it’s naive to think we’ll get the pill for Alzheimer’s,” Dr. Donald Weaver, a now-retired clinical neurologist and former director at Krembil Institute, told Being Patient. “Moreover, we don’t know if Alzheimer’s is one disease or many separate entities.”

He likens treating Alzheimer’s to other complex conditions like high blood pressure — which come with many different causes. People take different drugs depending on what’s causing their blood pressure to spike, and in the future, people might take specific Alzheimer’s drugs depending on their individual pathology.

THANK YOU for providing information to help us attempt to understand the complexity of the disease just diagnosed for my precious 65 year old sister. She is the former Director of Denver Parks & Recreation department for Special Needs even presented a lifetime ski pass for her mission for the benefit of residents. She has such an awesome attitude, continues to remain active playing pickle ball & skiing. Our hearts ache.